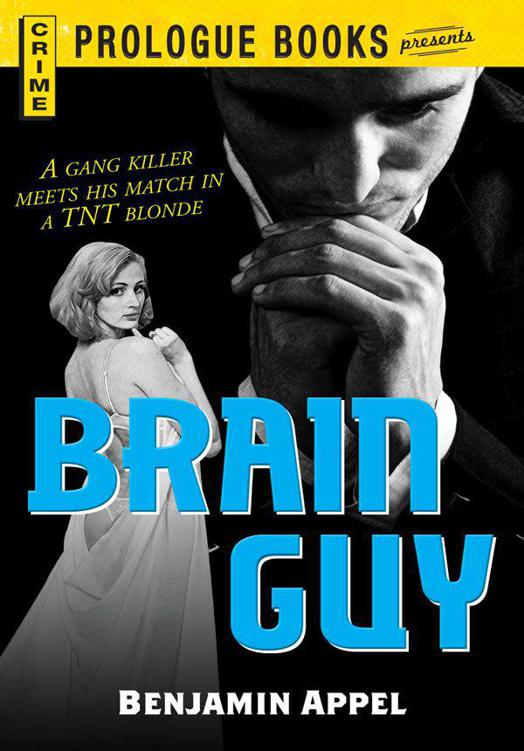

Brain Guy: A gang killer meets his match in a TNT blonde

Read Brain Guy: A gang killer meets his match in a TNT blonde Online

Authors: Benjamin Appel

Brain Guy

Benjamin Appel

a division of F+W Media, Inc.

a division of F+W Media, Inc.

To

My Mother and Father

W

HO COULD

he shake down for some dough? In the Italian table d’hôte he cracked the last walnuts with a spiteful feeling that the meal had cleaned him out, but who gave a damn? Eighty-five cents plus fifteen cent tip. That skunked a buck. Hell, he needed money. It’d been a jinx all day. None of his horses’d come in. The numbers’d been n. g. And pay-day was a mile off.

The cashier took his last buck. He strode back through the palms with the warlike solemnity of a fellow returning to tip a waiter or a barber. “Thanks, Mista Tren’,” said the waiter. “You got horse for me, mebbe?” He slid the dime and nickel out from his fingers. “Horicon in the fourth.”

The waiter appeared as if he’d been rewarded by a spendthrift.

On Forty-second Street and Eighth Avenue he paused in the thin fog floating in from the river. It was almost nine. From the sidestreet brothels and hotels the Greeks were going to their coffee-houses for a night of gambling. Hell, he needed money.

Eastwards Forty-second was a foam of yellow light. Following its course with his eyes, he somehow felt broker than hell. He was the crème de la crème to waiters, but the world’s biggest mug anywheres else. He thought about shaking down one of the speaks or joints that he managed discreetly as a real-estate collector. Who could he shake down without too much of a squawk? Crowds passed before him as if pinned immovable to metal strips. The crossroads of the world. The city of a million bugs chasing their behinds off for a few nickels. He was a louse, too, always broke, always in a panic to get some dough. Fastened to the fate of the metal strips, endless men and women were having their impact on his vision. Where were they going? What were their lives and what the hell was the difference?

He pulled up his coat collar, griped with himself for being groggy. He remembered his kid brother. He’d never had a good influence on the kid. Maybe it was too bad the kid was coming to town real soon. The kid was soft. He was hard-boiled. Being soft was nothing in the pocket. He decided to shake down Paddy, feeling swell inside as if he were turning over a new leaf.

He hurried north, playing with two pennies in his pocket. Whose fault was it he was nuts about money? It was the fault of the Big Stem, fault of the Big Stink. You simply had to have dough. Paddy ought to be good for ten bucks.

Entering the side street, he shuddered. The El was at the end of Paddy’s block. The tenement rows with their bleak staircases, the silence mean as a beggar’s, impelled him to mind his own business.

His hand slid along the banister. He seemed to flit upwards through a smell of cats. On each landing there was a solitary lonely light. On the third floor he knocked at Paddy’s door. The door slanted open an inch. Paddy peered out. The door edge cut down across his lips as if silencing them. The man whispered with the bitter humor of a stubborn wise-guy: “Ain’t I glad? Phenagling Bill. Hell.”

“Hello, Paddy.” He pushed past the hostile paunch. The stench of rotten whisky stood behind him like a doorman. It was damn cockeyed. Since when did Paddy chuck parties?

He saw all together, swiftly, the three small square rooms of the railroad flat, the peeling paint, a big trunk. A radio was howling. Two couples were dancing. The men were slim ginzos who appeared to be trying to stitch their bodies into the women. They stopped a second and glared at him with animal eyes. He didn’t like their looks. Wops weren’t up his alley. He nodded at the women. Bobbie and Madge were Paddy’s whores. He grinned. He wanted dough, but those ginzos were after girls. One of them was shouting at Paddy, suspicious. Bill was disgusted. Hell, he didn’t want no piece of those dames. The ginzos could keep them. He appealed to Paddy. “Let me see you private.”

The mick shook his big face. Sandpapered by age, his cheeks were large-pored. “Beat it. This is private.” But just the same he led Bill into the last room, slamming the French door. They were alone even if the beds spoke for Madge and Bobbie.

“Listen, Paddy, did I or did I not get a cut in your rent? Right. I did. And no one’s wise your joint’s here.”

“You got fifteen bucks outa me two weeks ago.”

“And was promised twenty-five. You think it a cinch keeping the boss from getting wise?”

“You eat money.” Paddy confronted him with the littlest of blue eyes, his face a pokerface all of a sudden. “You lousy heel.”

“Quit belly-aching. Give me the dough.”

“Yeh, yeh.” He flung the door open, announcing: “This guy’s Bill. He’s O.K.” Coming out of the room that led to the fire-escape, the others accepted him. It was different from coming in off the street. Since when did Paddy chuck parties, the chiseler, thought Bill. He didn’t like it. Was Paddy figuring to pay him off in merchandise? The pimp was rubbing his clean red jowls, sidling over to him with the comradeship of one stag for another. “Bill, you’re a guy.” He pulled up his trousers so the crease’d keep. “If I weren’t a good guy myself, I’d call you a lil sonufabitch.”

“How about my dough?”

“Sweat for it. I did. Who’d aguess it with that good-lookin’ mug of yourn. Madge is nuts about you.” He smiled at the dancers in the cleared space. The long hairs of middle age stuck out of his nostrils. His shirt was blue silk, his manners the old-fashioned ones of a pre-war bartender.

“All dames are nuts on me, but who gives a damn? Got my dough?” He peered sideways at the big nose and chin of Paddy, whispering: “Since when do you chuck parties? Fishy, ain’t it? If I didn’t need dough real bad, I’d get the hell out.”

“It’d be healthier.”

“You don’t faze me.”

“Don’t talk so loud.”

The radio stopped. Out on the floor Madge was telling her partner to take a good flying trip for his guts, hurrying off into the last room, where she sat down on the bed. In the faces of the women there was the strained impatience of plotters approaching a climax. Bill shivered. He felt as if he’d missed a signal. Madge’s deserted partner complained bitterly. Imagine chasing out on him. What was wrong? Did he stink?

Bobbie hugged the other ginzo. “I won’t run off, Tony.”

Tony laughed like a fool. He was in luck. His dame liked him. He squeezed her hand, his eyes innocent, betrayed. He was thinking of a good time, and the others, staring wickedly, thought of something else. Tony was pitted against them all.

Bill’s heart pounded. Something was up. Even Madge, young as she was, was hep. The shades were pulled down behind her. He hardly felt Paddy’s thumb jabbing into his side or heard the leering crack. Something was up. He had stumbled into it. Whatever was to be would be soon. Bill’s head ached. The silly talk was unbearable. Fascinated, sick, he observed the spectacle of a man blind to the hostile eyes, the thumbs turned down against him. The others faded from sharpness like figures in an old photograph. He knew that Bobbie and the two wops were there because they had existed a half-hour ago. But out of that time nothing was clear except Paddy and the kid sulking in the third room. These two were cut out of his agonized awareness. His back was turned on Madge, but he was seeing her in the dress the color of a green cordial. Wavering on thought like a reflection on water, he saw the thin girl face, the woman’s body.

The two ginzos were gabbing with fat Bobbie, while Paddy’s head, colossal because all their words and motives behind the words emanated from him, nodded pale and evil, the eyes bright, the lips cold with the humor of a murderer. These two, Madge and Paddy, were the omens of what was to come. Bill puffed on his cigarette. He thought: Bobbie is twenty-five, a whore. Tony is a fool if he can’t see how she’s faking him. He was horrified at dumb Tony pawing her, his teeth a flash of life. He is to die, thought Bill; they are about to kill him, I don’t know why. It doesn’t matter. Tony and Bobbie were dancing, their veins beating blood, the woman squirming her hips. Oh, there was something cockeyed in the flat, and everybody was wise except Tony. Paddy thumped his hand on Bill’s knee. He grinned, fraudulently delighted. “You’re a corker.” He poured rye into his glass. “Why’nt you beat it?”

“What you going to do to Tony?” He felt slimed to be sharking for a few lousy bucks when death was in the flat.

Paddy rolled up out of his chair with the finality of one leaving on a steamer, waving the bottle of rye, gleaming brown facets of light. There was no bringing Paddy back. He was gone.

Bill wanted to scream out: “You dumb ginzo, get the hell out before you’re carried out.” Tony was dancing at his own funeral. Twisting his eyes into the rear room, he saw Madge still sitting on the bed. He was thinking of the Irish eyes of her, the long, sweet, white limbs. In his heart there was desire and pity. Why didn’t he beat it while he had a chance? He couldn’t move from his chair, nerveless, morbidly curious, laughing when Paddy asked him if he liked the young un. Tony flopped down in a chair, Bobbie on his lap, her dress above her knees, her legs hanging. Her cheeks were blown full with song, singing in a loud nauseously sweet voice. It was to be. Now. Paddy eased across the floor, his body stiff, polite. Bill leaned forward. Paddy, who rarely raised his voice, was bellowing. Paddy was in love with noise, increasing the radio’s volume. Tony’s pal crept behind him.

Bill distinctly heard his heart miss a beat, then another. Madge was singing, her voice all quavers. He started. Why not holler, too? Holler holler, oh, my God! Across the way, people were shouting: “Shut up, for Pete’s sake.” “Can the racket.” “Cut it.” “Get the cops.” All the potential violence of their bodies exploded into noise. Bill wheeled round. Avoiding his eyes, Madge sang with the persistence of a set-off alarm-clock.

Dark-haired, both ginzos. Both must have hairy chests. The assassin stood directly behind Tony, stood in time itself that second like a statue on a pedestal. Paddy’s mouth was a rubbery circle changing shape. The statue moved out of inanimation. The knife was out. Tony’s pal lunged. Paddy winked at Bill as if to say: You’d hang around, huh?

Madge sobbed. Bobbie shot off the lap of the corpse.

It wasn’t a corpse. Yes it is, thought Bill. He was stunned to see death catch up so fast with what had been such a fine animal. A minute ago Bobbie had snuggled up against the ginzo, walling him with her fat flesh so that his face was hidden, and all there was of a man were the two legs in their trousers. The legs are dead now, thought Bill. He is dead all over and lying on the floor all over. The sleek head was on the dirty carpet. The assassin wiped his blade. Even Bobbie had no guts for this, her rouge a mask plastered on pallor. The radio sang with the complacency of a robot. “Couldn’t get you out, you sonufabitch,” said Paddy. “You’re in it.”

Over and over again the slaughter re-acted itself, grinding his nerves like a needle stuck in a groove on a phonograph record. The chair in which Tony had sat was ventilated. Empty space cut through the middle by a decorative slice of wood. The knife had been lunged through the slit. What the hell was wrong with him? That was a dead man on the floor, no tailor’s dummy. But still he didn’t give a damn one way or the other. The wop was the pawn in a game he wasn’t hep to. He heard himself saying: “I’m not in it. But how crazy to spot Tony with all this gang about!” This was what struck him above all else. To murder with such a crowd about. That was dumb. There was a thing called the law. Tony wasn’t a cow that could be killed legit.