Brain on Fire (7 page)

Authors: Susannah Cahalan

When I got home at seven that night, Stephen was already waiting for me. Instead of telling him I’d been out with Angela, I lied and told him I had been at work, convinced that I needed to hide my perplexing behavior from him, even though Angela had urged me to just tell him the truth. But I did warn him that I wasn’t acting like myself and hadn’t been sleeping well.

“Don’t worry,” he responded. “I’ll open a bottle of wine. That will put you to sleep.”

I felt guilty as I watched Stephen methodically stir the sauce for shrimp fra diavolo with a kitchen towel tucked in his pant loops. Stephen was a naturally skilled and inventive cook, but I couldn’t enjoy the pampering tonight; instead, I stood up and paced. My thoughts were running wild from guilt to love to repulsion and then back again. I couldn’t keep them straight, so I moved my body to quiet my mind. Most of all, I didn’t want him to see me in this state.

“You know, I haven’t really slept in a while,” I announced. In fact, I couldn’t remember the last time I had slept. I had gone without real sleep for at least three days, and the insomnia had been plaguing me for weeks, on and off. “I might make it hard for you to sleep.”

He looked up from the pasta and smiled. “Don’t worry. You’ll sleep better with me around.”

He handed me a plate with pasta and a healthy helping of parmesan. My stomach turned at the sight, and when I tasted the shrimp, I almost gagged. I pushed the pasta around on my plate as he devoured his. I watched him, trying to hide my disgust.

“What? You don’t like it?” he asked, hurt.

“No, it’s not that. I’m just not hungry. Great leftovers,” I said cheerfully, while having to physically restrain myself from pacing around the apartment. I couldn’t stay with one thought; my mind was flooded with different desires, but especially the urge to escape. Eventually I relaxed enough to lie down on my couch bed with Stephen. He poured me a glass of wine, but I left it on the windowsill. Maybe I knew on some primal level that it would have been bad for my state of mind. Instead, I chain-smoked cigarettes, one after another, down to their nubs.

“You’re a smoking fiend tonight,” he said, putting his own cigarette out. “Maybe that’s why you’re not hungry.”

“Yeah, I should stop,” I said. “I feel like my heart is beating out of my chest.”

I handed Stephen the remote, and he flipped the channel to PBS. As his heavy breathing turned into all-out snores,

Spain . . . on the Road Again

came on, the reality show that followed actress Gwyneth Paltrow, chef Mario Batali, and

New York Times

food critic Mark Bittman through Spain.

God, not Gwyneth Paltrow,

I thought, but was too lazy to change the channel. As Batali ate luscious eggs and meat, she toyed with a thin goat’s-milk yogurt, and when he offered her a bite of his dish, she demurred.

“That’s nice to have at seven in the morning,” she said sarcastically.

4

You could just tell how disgusted she was by his belly.

As I watched her nibble on her yogurt, my stomach turned. I thought about how little I had eaten in the past week.

“Hold on,” he retorted. “I can’t see you on that high horse of yours.”

I laughed right before everything went hazy.

Gwyneth Paltrow.

Eggs and meat.

Darkness.

OUT-OF-BODY EXPERIENCE

A

s Stephen later described that nightmarish scene, I had woken him up with a strange series of low moans, resonating among the sounds from the TV. At first he thought I was grinding my teeth, but when the grinding noises became a high-pitched squeak, like sandpaper rubbed against metal, and then turned into deep,

Sling Blade

–like grunts, he knew something was wrong. He thought maybe I was having trouble sleeping, but when he turned over to face me, I was sitting upright, my eyes wide open, dilated but unseeing.

“Hey, what’s wrong?”

No response.

When he suggested I try to relax, I turned to face him, staring past him like I was possessed. My arms suddenly whipped straight out in front of me, like a mummy, as my eyes rolled back and my body stiffened. I was gasping for air. My body continued to stiffen as I inhaled repeatedly, with no exhale. Blood and foam began to spurt out of my mouth through clenched teeth. Terrified, Stephen stifled a panicked cry and for a second he stared, frozen, at my shaking body.

Finally, he jumped into action—though he’d never seen a seizure before, he knew what to do. He laid me down, moving my head to the side so that I wouldn’t choke, and raced for his phone to dial 911.

I would never regain any memories of this seizure, or the ones to come. This moment, my first serious blackout, marked the line between sanity and insanity. Though I would have moments of lucidity over the coming weeks, I would never again be the same person. This was the start of the dark period of my illness, as I began an existence in purgatory between the real world and a cloudy, fictitious realm made up of hallucinations and paranoia. From this point on, I would increasingly be forced to rely on outside sources to piece together this “lost time.”

As I later learned, this seizure was merely the most dramatic and recognizable of a series of seizures I’d been experiencing for days already. Everything that had been happening to me in recent weeks was part of a larger, fiercer battle taking place at the most basic level inside my brain.

The healthy brain is a symphony of 100 billion neurons, the actions of each individual brain cell harmonizing into a whole that enables thoughts, movements, memories, or even just a sneeze. But it takes only one dissonant instrument to mar the cohesion of a symphony. When neurons begin to play nonstop, out of tune, and all at once because of disease, trauma, tumor, lack of sleep, or even alcohol withdrawal, the cacophonous result can be a seizure.

For some people, the result is a “tonic-clonic” seizure like the one Stephen witnessed, characterized by loss of consciousness or muscle rigidity and a strange, often synchronized dance of involuntary movements—my terrifying zombie moves. Others may have more subtle seizures, which are characterized by staring episodes, foggy consciousness, and repetitive mouth or body movements. The long-term ramifications of untreated seizures can include cognitive defects and even death.

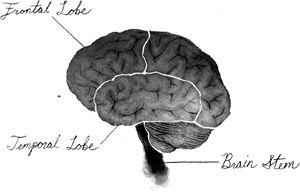

The type and severity of a seizure depend on where the neural dysfunction is focused in the brain: if it is in the visual cortex, the person experiences optical distortions, such as visual hallucinations; if it is in the motor areas of the frontal cortex, the person exhibits strange, zombie-like movements; and so forth.

Along with the violent tonic-clonic seizure, it turned out I had also been experiencing complex partial seizures because of overstimulation in my temporal lobes, generally considered to be the most “ticklish” part of the brain.

5

The temporal lobe houses the ancient structures of the hippocampus and the amygdala, the parts of the brain responsible for emotion and memory. The symptoms from this type of seizure can range from a “Christmas morning” feeling of euphoria to sexual arousal to religious experiences.

6

7

Often people report feeling déjà vu and its opposite, something called jamais vu, when everything seems unfamiliar, such as my feeling of alienation in the office bathroom; seeing halos of light or viewing the world as if it is bizarrely out of proportion (known as the Alice in Wonderland effect), which is what was happening while I was on my way to interview John Walsh; and experiencing photophobia, an extreme sensitivity to light, like my visions in Times Square. These are all common symptoms or precedents of temporal lobe seizures.

A small subset of those with temporal lobe epilepsy—about 5 to 6 percent—report an out-of-body experience, a feeling described as being removed from your body and able to look at yourself, usually from above.

8

There I am on a gurney.

There I am being loaded into the ambulance as Stephen holds my hands.

There I am entering a hospital.

Here I am. Floating above the scene, looking down. I am calm. There is no fear.

A TOUCH OF MADNESS

W

hen I gained consciousness the first thing I saw was a homeless man vomiting just a few feet away in a brightly lit hospital room. In one corner, another man, bloodied, beaten, and handcuffed to the bed, was flanked by two police officers.

Am I dead?

Anger at my surroundings welled up inside me.

How dare they put me here.

I was too incensed to be terrified, and so I lashed out. I hadn’t felt like myself for weeks, but the real damage to my personality was only now bubbling to the surface. Looking back at this time, I see that I’d begun to surrender to the disease, allowing all the aspects of my personality that I value—patience, kindness, and courteousness—to evaporate. I was a slave to the machinations of my aberrant brain. We are, in the end, a sum of our parts, and when the body fails, all the virtues we hold dear go with it.

I am not dead yet. I am dying because of him, because of that lab technician.

I convinced myself that the tech who may have flirted with me when I had my MRI was clearly behind all this.

“Get me out of this room NOW,” I commanded. Stephen held my hand, looking frightened by the imperiousness in my voice. “I will NOT stay in this room.”

I will not die here. I will not die with these freaks.

A doctor approached my bedside. “Yes, we will move you right away.” I was triumphant, delighted by my newfound power.

People listen when I speak.

Instead of worrying that my life was out of control, I began to focus on anything that made me feel strong. A nurse and a male assistant wheeled my bed out of the room and into a nearby private one. As the bed moved, I clutched Stephen’s hand. I felt so sorry for him. He didn’t know that I was dying.

“I don’t want you to get upset,” I said softly. “But I’m dying of melanoma.”

Stephen looked spent. “Stop it, Susannah. Don’t say that. You don’t know what’s wrong.” I noticed tears welling up in his eyes.

He can’t handle it.

Suddenly the outrage returned.

“I do know what’s wrong!” I yelled. “I’m going to sue him! I’m going to take him for all he’s worth. He thinks he can hit on me and just let me die? He can’t just do that. No, I’m going to destroy him in court!”

Stephen withdrew his hand swiftly, as if he’d been burned. “Susannah, please stay calm. I don’t know what you’re talking about.”

“The MRI guy! He hit on me! He didn’t catch the melanoma. I’m suing!”

The young resident interrupted me mid-rant. “This is something you might want to look into when you get home. If you need a good dermatologist, I would be happy to recommend one. Unfortunately, there’s nothing more we can do here.” The hospital had already conducted a CT scan, a basic neurological exam, and a blood test. “We have to discharge you and advise that you see a neurologist first thing tomorrow.”

“Discharged?” Stephen interjected. “You’re letting her go? But you don’t know what’s wrong, and it could happen again. How can you just let her go?”