Bread Matters (33 page)

Authors: Andrew Whitley

Never

microwave a croissant. I was once served one for breakfast on a plane; only the vague outline of its shape distinguished it from the hot towel that was dished out shortly afterwards.

Danish Pastries

This is another product that has been degraded from the special to the everyday by a food industry eager to advance the illusion that luxury can be a perpetual condition, forgetting that it is only in contrast to the plain that the fancy has any meaning. The road from treat to commodity is paved with cheap ingredients, manipulated to make less seem more.

Making Danish pastries at home with simple, real ingredients is a revelation – and anything as time consuming and fiddly as this is destined to remain the occasional indulgence that good sense suggests it should only ever have been.

The dough for Danish pastries is different from a croissant dough only in that it contains some sugar and egg and so is slightly richer and cakier. The rolling and folding method is the same as for croissants.

Makes 16 pastries

15g Fresh yeast

180g Milk (cold)

500g Strong white flour

2g Ground cardamom

15g Raw cane sugar

2g Sea salt

100g Egg (2 eggs)

Zest of 1 lemon

815g Total

250g Butter (slightly salted or unsalted)

Fruit purée (such as apple, apricot, gooseberry or blackcurrant) for filling

A few dried apricots

Beaten egg, to glaze

Dissolve the yeast in the milk and add to the other ingredients. Knead into a smooth, elastic dough, as for croissants. Laminate with the butter and fold exactly as for croissants. After the final turn, roll the dough out into a large rectangle about 6mm thick.

There are many possible shapes for Danish pastries, ranging from wheels, like the Marzipan Wheels described above, to strudel-shaped strips. The following is a classic shape, suitable for a soft filling.

Cut pieces of dough about 10cm square. Make a cut right through the dough from each of the corners halfway towards the centre point. Place a generous teaspoonful of fruit purée on the middle of the dough. Fold one half of each split corner over so that its end reaches the middle point on top of the filling. Gently press the 4 ends down on the filling and weight them down with a dried apricot or similar piece of fruit.

Carefully brush the exposed areas of dough with beaten egg. Cover and prove as for croissants. Bake in a moderate oven (180°C) and take care not to allow any rich, sugary filling to take too much colour.

After baking, glaze with a honey glaze (see page 249) or drizzle with the following lemon icing:

Lemon icing

30g Butter

30g Golden caster or granulated sugar

30g Lemon juice

110g Icing sugar

200g Total

Melt the butter over a low heat and add the caster or granulated sugar and the lemon juice. Mix together until combined. Pour this mixture on to the icing sugar and whisk until smooth.

Lardy Cake

Lardy cake was a treat for the English rural poor. In its simplest manifestations it involved no more than a piece of ordinary bread dough with some sugar and lard rolled into it. It is associated with the pig-rearing areas of southern England, notably Wiltshire, but was probably more widespread in times gone by. Some versions used not lard but scratchings, the residue after pig fat had been melted and clarified.

While the very name is enough to make a centrally heated vegetarian queasy, lardy cake is packed with just the sort of tasty calories required to sustain hard manual work in winter. If you would rather not use lard, butter works just as well. The loaf is assembled using the rolling and folding method already seen in croissants and Danish pastries. The end result is not as fine, but it is unpretentiously English.

I haven’t come across organic lard yet, though it ought to be a by-product of organic pork production. Until it appears in shops, you might prefer to use butter from happy organic cows than lard from intensively reared non-organic pigs.

Makes 2 small lardy cakes

605g Hot Cross Bun Dough (see page 256)

100g Lard or butter

100g Light muscovado sugar

805g Total

Prepare the Hot Cross Bun Dough as described on page 256, using some candied mixed peel in the fruit mix if desired.

Cream the lard or butter and sugar together. Roll the dough out into a rectangle, as for croissants. Spread two-thirds of this with the lard/sugar mixture. Fold up in 3 and then give 2 book turns, as for croissants. The rests between turns can be shorter, since their object is purely to relax the gluten rather than to keep the butter scrupulously cold.

After the final turn, pin the dough out into a rectangle and then roll it up tightly like a Swiss roll. Cut this in half and place each piece, cut edge down, into a greased small loaf tin or an 18cm round cake tin.

Cover, prove at ambient temperature and bake in a moderate to hot oven (190°C) for about 30 minutes. Tradition has it that the loaf should be tipped out of the tin and cooled upside down to allow the fat to run back into it.

CHAPTER TWELVE GLUTEN-FREE BAKING

‘The industry has concentrated its economic and technological effort into the production of a nutritionally inferior loaf. More and more people are phasing bread out of their diet, indicating that the bread industry has failed both the consumer and itself…The consumer has a right to full information and thorough government protection on matters affecting the nutritional value and safety of food.’

Bread: An Assessment of the British Bread Industry

(The Technology Assessment Consumerism Centre (TACC) Report, Intermediate Publishing, 1974)

Coeliac disease is a serious digestive disorder. The only treatment is to avoid gluten. For life.

So how does the food industry cater for coeliacs – people who, by definition, must be eternally vigilant over what they eat? Why, by stuffing gluten-free products with substances such as methylcellulose (E461) and xanthan gum. These, like the plethora of additives, colours and flavours used to brighten up otherwise dull and tasteless products, are not, of course, ‘foods’. Our ancestors did not cultivate or gather them, so we have no evolutionary experience of eating them. Maybe they are harmless. But maybe they are not. Perhaps people with a sensitivity to gluten deserve better than to be fobbed off with highly processed chemical additives. If coeliacs are already excluded, through an accident of genetics, from bread made with wheat, rye, barley or oats, perhaps they are entitled to the most nutritious alternative. Well, they might have to make it themselves.

What’s wrong with additives?

In case you think I am being unfair to additives and ‘processing aids’, all of which are approved by learned committees before they can be used in food, just consider the alarming news about transglutaminase. In a recent study this enzyme, which is added to bread, pastry and croissants, was shown to act on the gliadin proteins in dough to generate the peptides responsible for triggering the coeliac response in susceptible people (see page 15). This is just one enzyme, of course, and I am not suggesting that all additives have such harmful potential. But it is surely common sense for people such as coeliacs and those known to be sensitive to wheat to avoid possible stress to their already compromised digestive systems by taking a cautious approach. After all, these additives are not food: they are only there to enable the manufacturers to present their product in an attractive form.

There are a few companies making gluten-free products without weird additives. But too often the food industry uses its ingenuity and functional additives to make overprocessed ingredients into superficially attractive but indifferent products, rather than saying to itself: ‘How can we make the most nutritious food possible out of the ingredients which these people can eat?’ When you can tolerate only a limited range of raw materials, it is especially important that every aspect of your diet is as wholesome as possible.

(Dis)comfort food

In the case of gluten-free bread, bakers use all the chemical contrivances in the book to create something that displays as many of the characteristics of standard white wheat bread as possible, such as:

- Soft, squishy texture.

- Enzyme-extended shelf life.

- Reduced dietary fibre and micronutrients (compared to whole wheat).

- Excessive baker’s yeast.

- Minimal fermentation time, leading to suspect digestibility.

- Bland flavour.

- Significant dose of artificial additives.

If it is argued (as it often is) that this is exactly ‘what the gluten-free market wants’, I can only suggest that people with dietary sensitivities deserve something better than such self-serving infantilism. We sometimes give infants what they appear to like, irrespective of its quality, in order to avoid a tantrum. But if we are wise, we teach our children as they grow up that immediate gratification has to be balanced against future benefit and that with food, as with many other things in the real world, some effort may be required to gain a reward worth having.

Good reasons to bake gluten-free

So, if you or a family member has coeliac disease, or if you are avoiding or reducing gluten in your diet, you will naturally want to fill the gaps in your menu with wholesome, appetising food. Baking your own is the answer, for two reasons. First, you can control what goes into your food and avoid all the rubbish described above. Second, you can save money. Shop-bought gluten-free bakery products can be expensive, partly because there are fewer economies of scale than in the massive wheat-based market, and partly because there is less competition between suppliers. Registered coeliacs can, of course, get gluten-free food on prescription but the choice is limited, almost invariably, to products whose long shelf life is dependent on artificial preservatives.

After a bit of experimentation, you will probably decide that you need just a few gluten-free flours to make most of your breads, cakes and biscuits. You can then arrange to buy these in reasonable quantities to keep the cost down.

Why gluten-free baking is different

So you want to avoid the unpronounceable additives and you wouldn’t mind saving a few quid. You’re going to bake your own, gluten-free. Before you start, you need to learn a few principles – and

unlearn

a few more.

Wheat gluten is unique. A grain of breadmaking wheat contains 12-15 per cent protein, whose main fractions are known as glutenin and gliadin. When these are made into a dough with water and subjected to physical mixing or kneading, an insoluble ‘visco-elastic’ web is formed. This is the gluten. It can be visualised as a series of tiny balloons, which expand when they are inflated by the gases from fermenting yeast. The result is a light, open dough structure that holds together well.

The gluten in rye, barley and oats does not have the ability to form the same stretchy network as wheat gluten. These flours make very different breads from wheat, though their gluten is still toxic to coeliacs.

Wheat gluten is amazing. It can form part of a dough that will expand to several times its original volume, that can be formed into an elaborate shape which is maintained throughout the baking process, and that produces bread with a variety of textures – soft, chewy, rubbery, firm, leathery, crunchy – to suit almost every occasion and taste.

Lower-protein wheats contain less gluten and are therefore used for making pastries, biscuits and cakes. These things need a ‘short’, crumbly, melt-in-the-mouth consistency and too much gluten (or a gluten network that is over-developed) will make them tough and chewy.

If you take the gluten out of wheat (yes, I’m afraid that there is such a thing as de-glutenised wheat flour), it will not make ordinary bread. Neither will other flours (such as rice, millet, soya etc) that do not contain gluten in the first place. This may seem obvious, but it needs to be emphasised. Making bread without gluten can be done, but it will not be the same as ordinary bread. It may be as nutritious and as delicious, but it is not the same. How could it be, when it lacks the very thing that defines bread?

I know how hard this can be for people who have to avoid gluten, especially for those forced to end a lifelong love affair with bread. What they really want is something that looks, tastes and behaves like ‘proper’ bread. It cannot be done. Unless, that is, you are prepared to let the food technologists loose with their chemistry sets. They are ingenious souls and can probably contrive something pretty plausible. But will it be food?

My approach is not to mourn the absence of gluten but to relish the qualities of flours that do not contain it. After all, despite wheat’s global importance, many cultures feed themselves very nicely without it. By thinking creatively about ingredients and processes, we can turn out things that are good to eat.

Gluten-free baking is not just ordinary baking without certain ingredients. It requires a few adjustments, of mind and method.

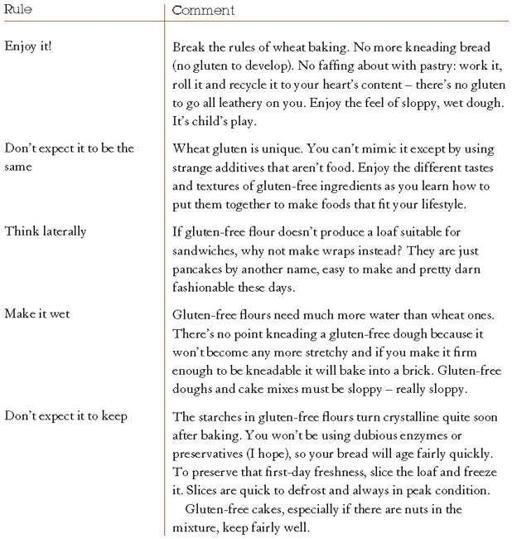

Rules for gluten-free baking