Bridget Jones: Mad About the Boy (39 page)

Read Bridget Jones: Mad About the Boy Online

Authors: Helen Fielding

Friday 27 September 2013

9.45 p.m.

‘It’s you he loves,’ said Tom, on his fourth mojito in the York & Albany.

‘Look, can we just shut up about Mr Effing Wallaker?’ I muttered.

‘I’ve accepted my life now. It’s good. It’s the three of us. We’re not broke. I’m not lonely any more. I’m a great tree.’

‘And

The Leaves in His Hair

is going to be made!’ encouraged Jude.

‘What’s left of it,’ I said darkly.

‘But at least you’ll get to go to the premiere, baby,’ said Tom. ‘You might meet someone there.’

‘If I’m invited.’

‘If he’s not calling you, if he’s not texting you, he’s just not that into you,’ said Jude unhelpfully.

‘But Mr Wallaker has never called her or texted her,’ said Tom squiffily. ‘Who are we talking about here?’

‘Can we please stop talking about Mr Wallaker? I don’t even like him and he doesn’t like me.’

‘Well, you did rather give him an earful, darling,’ said Talitha.

‘But there was so much depth to what was building,’ said Tom.

‘When he’s hot, he’s hot; when he’s not, he’s not,’ said Jude.

‘Why don’t you get Rebecca to fix you up?’ said Tom.

10 p.m.

Just went round to Rebecca’s. She shook her head. ‘It never works, that sort of thing. They sense it a mile off, by radar. Just let it unfold.’

THE MIGHTY JUNGLE

Friday 18 October 2013

Number of times listened to ‘The Lion Sleeps Tonight’ 45 (continuing).

9.15 p.m.

The choir auditions have come round again. Billy is lying in bed singing ‘The Lion Sleeps Tonight’, then going, ‘Eeeeeeeeeeeeoheeeeoheeeeoh’ in a high-pitched voice while Mabel yells, ‘Shut up, Billy, shut uuuuuuuuuuurp.’

This year we have been practising hitting actual notes. Was in fact quite carried away with self this evening, teaching them Doh Ray Me, parroting Maria in

The Sound of Music

(I actually do know the whole of

The Sound of Music

off by heart).

‘Mummy?’ said Billy.

‘Yes?’

‘Can you stop, please?’

Monday 21 October 2013

Times practised ‘The Lion Sleeps Tonight’ before school 24, hours spent worrying whether Billy will get into choir 7, times changed outfit to pick up Billy from choir auditions 5, minutes early for pickup 7 (good, apart from reasons for same: i.e. impressing hopeless love prospect).

3.30 p.m.

Just about to pick up Billy and get choir audition results. Beside self with nerves.

6 p.m.

Freakishly was already waiting inside the school gates before Billy came out. I saw Mr Wallaker emerge onto the steps and glance round, but he ignored me. Was sunk into gloom, realizing that now

he was officially single, he feared that all single women, including me, were going to nibble at him like piranhas.

‘Mummy!’ Billy emerged, grinning the fantastic ear-to-ear grin, as though his face was going to burst. ‘I got in! I got in! I got in the choir!’

Delirious with joy I encircled him in my arms at which he grunted, ‘Ge’ awfff!’ like an adolescent and glanced nervously at his friends.

‘Let’s go and celebrate!’ I said. ‘I’m so proud of you! Let’s go to . . . to McDonald’s!’

‘Well done, Billy.’ It was Mr Wallaker. ‘You kept trying and you made it. Good effort.’

‘Um!’ I said, thinking maybe this was the moment when I could apologize and explain, but he just walked off, leaving me with only his pert bum to look at.

I just ate two Big Macs with fries, a double chocolate shake and a sugar doughnut.

When he’s hot, he’s hot; when he’s not, he’s not. But at least there is always food.

PARENTS’ EVENING

Tuesday 5 November 2013

9 p.m.

Hmmm. Maybe he isn’t not hot. I mean, not completely not hot. Arrived at parents’ evening, admittedly a tad late, to find most of the parents preparing to leave and Billy’s form teacher, Mr Pitlochry-Howard, looking at his watch.

Mr Wallaker strode in with an armful of reports. ‘Ah, Mrs Darcy,’ he said. ‘Decided to come along after all?’

‘I have been. At a meeting,’ I said hoity-toitily (even though, unaccountably, as yet, no one has asked for a meeting about

Time Stand Still Here

, my updating of

To the Lighthouse

) and settled myself with an ingratiating smile in front of Mr Pitlochry-Howard.

‘How IS Billy?’ said Mr Pitlochry-Howard kindly. Always feel uncomfortable when people say this. Sometimes it’s nice if you think that they really care, but I paranoically imagined he meant there was something wrong with Billy.

‘He’s fine,’ I said, bristling. ‘How is he, you know, at school?’

‘He seems very happy.’

‘Is he all right with the other boys?’ I said anxiously.

‘Yes, yes, popular with the boys, very cheerful. Gets a bit giggly in the class sometimes.’

‘Right, right,’ I said, suddenly remembering Mum getting a letter from my headmistress suggesting that I had some sort of pathological giggling

problem

. Fortunately Dad went in and gave the teacher an earful, but maybe it was a genetic disorder.

‘I don’t think we need to worry too much about giggling,’ said Mr Wallaker. ‘What was the issue you had with the English?’

‘Well, the spellings . . .’ Mr Pitlochry-Howard began.

‘Still?’ said Mr Wallaker.

‘Ah, well, you see,’ I said, springing to Billy’s defence. ‘He’s only little. And also –

as

a writer I believe language is a constantly evolving, fluctuating thing, and actually communicating what you want to say is more important than spelling and punctuating it.’ I paused for a moment, remembering Imogen at Greenlight accusing me of just putting strange dots and marks in here and there where I thought they looked nice.

‘I mean, look at “realize”,’ I went on. ‘It used to be spelt with a z and now it’s Americanized – that’s with an “s” by the way. And I notice you’re spelling it on the tests with an “s” because computers do now!’ I finished triumphantly.

‘Yes, marvelous, with a single “l”,’ said Mr Wallaker. ‘But, at this present moment in time, Billy needs to pass his spelling tests or he’ll feel like a berk. So could you perhaps practise when you two are running up the hill in the mornings just after the bell has rung?’

‘OK,’ I said, looking at him under lowered brows. ‘How is his actual writing? I mean, creatively?’

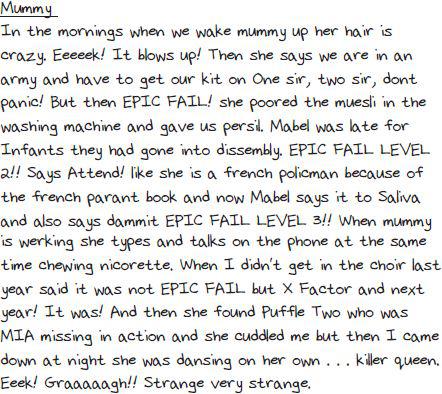

‘Well,’ said Mr Pitlochry-Howard, rustling through his papers. ‘Ah, yes. We asked them to write about something strange.’

‘Let me see,’ said Mr Wallaker, putting on his glasses. Oh God. It would be so great if we could both put on our reading glasses on a date without feeling embarrassed.

‘Something strange, you say?’ He cleared his throat.

I sank into the chair, dismayed. Was this how my children saw me?

Mr Pitlochry-Howard was staring down at his papers, red-faced.

‘Well!’ said Mr Wallaker. ‘As you say, it communicates what it’s trying to communicate very well. A very vivid picture of . . . something strange.’

I met his gaze levelly. It was all right for him, wasn’t it? He was trained in giving orders and had packed his boys off to boarding school and could use the holidays to casually perfect their incredible music and sporting skills while adjusting their spelling of ‘inauspicious’.

‘How about the rest of it?’ he said.

‘No. He’s – his marks are very good apart from the spelling. Homework’s still pretty disorganized.’

‘Let’s have a look,’ said Mr Wallaker, rifling through the science papers, then picking up the planets one.

‘“Write five sentences, each including a fact about Uranus.”’

He paused. Suddenly could feel myself wanting to giggle.

‘He only did one sentence. Was there a problem with the question?’

‘I think the problem was it seemed rather a lot of facts to come up with, about such a featureless galactical area,’ I said, trying to control myself.

‘Oh, really? You find Uranus featureless?’ I distinctly saw Mr Wallaker suppress a giggle.

‘Yes,’ I managed to say. ‘Had it been Mars, the famed Red Planet, with recent robot landings, or even Saturn with its many rings—’

‘Or Mars with its twin

orbs

,’ said Mr Wallaker, glancing, I swear, at my tits before staring intently down at his papers.

‘Exactly,’ I got out in a strangled voice.

‘But, Mrs Darcy,’ burst out Mr Pitlochry-Howard, with an air of injured pride, ‘I personally am more fascinated by Uranus than—’

‘Thank you!’ I couldn’t help myself saying, then just totally gave in to helpless laughter.

‘Mr Pitlochry-Howard,’ said Mr Wallaker, pulling himself together, ‘I think we have admirably made our point. And,’ he murmured in an undertone, ‘I can quite see whence the giggling originates. Are there any more issues of concern with Billy’s work?’

‘No, no, grades are very good, gets on with the other boys, very jolly, great little chap.’

‘Well, it’s all down to you, Mr Pitlochry-Howard,’ I said creepily. ‘All that teaching! Thank you

so

much.’

Then, not daring to look at Mr Wallaker, I got up and glided out of the hall.

However, once outside I sat in the car thinking I needed to go back in and ask Mr Pitlochry-Howard more about the homework. Or maybe, if Mr Pitlochry-Howard should, perchance, be busy, Mr Wallaker.

Back in the hall Mr Pitlochry-Howard and Mr Wallaker were talking to Nicolette and her handsome husband, who had his hand supportively on Nicolette’s back.

You’re not supposed to listen to the other parents’ consultations but Nicolette was projecting so powerfully it was impossible not to.

‘I just wonder if Atticus might be a little overextended,’ Mr Pitlochry-Howard was mumbling. ‘He seems to have so many after-school clubs and play dates. He’s a little anxious sometimes. He becomes despairing if he doesn’t feel he is on top.’

‘Where is he in the class?’ said Nicolette. ‘How far is he from the top?’

She peered over at the chart, which Mr Pitlochry-Howard put

his arm across. She flicked her hair crossly. ‘Why don’t we know their relative performance levels? What are the class positions?’

‘We don’t do class positions, Mrs Martinez,’ said Mr Pitlochry-Howard.

‘Why not?’ she said, with the sort of apparently pleasant, casual inquisitiveness which conceals a swordsman poised behind the arras.

‘It’s really about doing their personal best,’ said Mr Pitlochry-Howard.

‘Let me explain something,’ said Nicolette. ‘I used to be CEO of a large chain of health and fitness clubs, which expanded throughout the UK and into North America. Now I am CEO of a family. My children are the most important, complex and thrilling product I have ever developed. I need to be able to assess their progress, relative to their peers, in order to adjust their development.’

Mr Wallaker was watching her in silence.

‘Healthy competition has its place but when an obsession with relative position replaces a pleasure in the actual subject . . .’ Mr Pitlochry-Howard began nervously.

‘And you feel that extra-curricular activities and play dates are stressing him out?’ said Nicolette.

Her husband put his hand on her arm: ‘Darling . . .’

‘These boys need to be rounded. They need their flutes. They need their fencing. Furthermore,’ she continued, ‘I do

not

see social engagements as “play dates”. They are team-building exercises.’

‘THEY ARE CHILDREN!’ Mr Wallaker roared. ‘They are not corporate products! What they need to acquire is not a constant massaging of the ego, but confidence, fun, affection, love, a sense of self-worth. They need to understand, now, that there will always – always – be someone greater and lesser than themselves, and that their self-worth lies in their contentment with who they are, what they are doing and their increasing competence in doing it.’

‘I’m sorry?’ said Nicolette. ‘So there’s no point trying? I see. Then, well, maybe we should be looking at Westminster.’

‘We should be looking at who they will become as adults,’ Mr

Wallaker went on. ‘It’s a harsh world out there. The barometer of success in later life is not that they always win, but how they deal with failure. An ability to pick themselves up when they fall, retaining their optimism and sense of self, is a far greater predictor of future success than class position in Year 3.’

Blimey. Had Mr Wallaker suddenly been reading

Buddha’s Little Instruction Book

?

‘It’s not a harsh world if you know how to win,’ purred Nicolette. ‘What is Atticus form position, please?’

‘We don’t give form positions,’ said Mr Wallaker, getting to his feet. ‘Is there anything else?’

‘Yes, his French,’ said Nicolette, undaunted. And then they all sat down again.

10 p.m.

Perhaps Mr Wallaker is right about there being always someone ‘greater and lesser than yourself’ at things. Was just walking back to car when posh, exhausted mother trying to wrangle three overdressed children suddenly burst out, ‘Clemency! You fucking, bleeding

little

c***!’