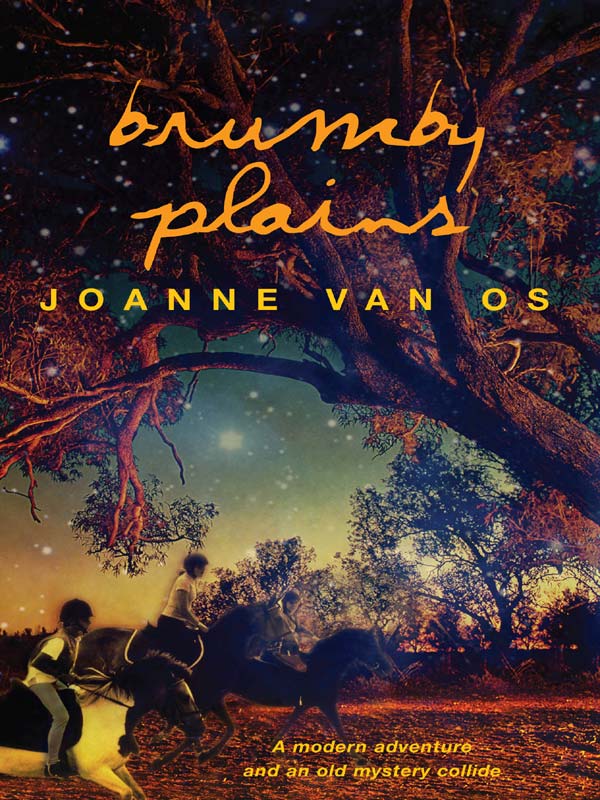

Brumby Plains

Authors: Joanne Van Os

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted by any person or entity, including internet search engines or retailers, in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including printing, photocopying (except under the statutory exceptions provisions of the Australian

Copyright Act 1968

), recording, scanning or by any information storage and retrieval system without the prior written permission of Random House Australia. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author's and publisher's rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

Brumby Plains

ePub ISBN 9781742745329

Random House Australia Pty Ltd

Level 3, 100 Pacific Highway, North Sydney, NSW 2060

http://www.randomhouse.com.au

Sydney New York Toronto

London Auckland Johannesburg

First published by Random House Australia in 2006

Copyright © Joanne van Os 2006

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be

reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted

in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical,

photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

National Library of Australia

Cataloguing-in-Publication Entry

van Os, Joanne.

Brumby Plains.

For confident readers aged 9+.

ISBN 978 1 74166 147 7.

ISBN 1 74166 147 1.

I. Title.

A823.4

Cover photography by Getty Images and Ellie Exarchos

Cover design by Ellie Exarchos

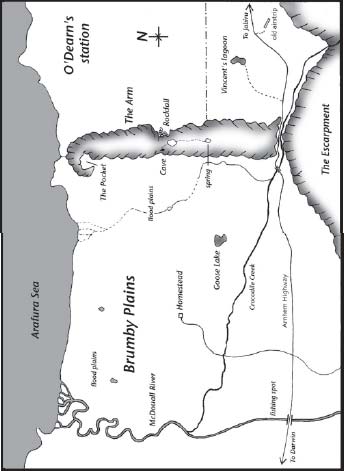

Internal illustrations of the banded fruit dove and map by Joanne van Os

For Ali van Os

The Aboriginal references in this story have been drawn from my own experiences over a long association with the Northern Territory and its people. The actual people, clans and names are entirely fictional, and are not based on any real group, current or historical. The geography of the area in which Brumby Plains is situated is also imaginary, created out of the various places in the Northern Territory's Top End in which I have lived.

The child was running for his life. His feet were a blur over the uneven ground as he dodged and weaved his way through the tangled scrub. Although branches snatched at his skin and tore at his hair, he was oblivious to everything but the terror that drove him on.

His right arm dangled limply by his side, blood dripping from an ugly gash that ran from his elbow to his wrist. He tripped, sprawling full length

among the roots of a big tree, and lay there momentarily stunned and gasping for breath. Then, with a strangled sob, he scrambled to his feet, and began to run as he had never run before.

Sam yawned hugely and looked at the schoolroom clock again. Still more than an hour to go before morning tea. He could hear his brother on the radio at the other end of the room, answering a question from his teacher, his voice rising with the effort to be heard through the static. The heat was mounting in the caravan that served as their classroom, and it was only 9 am.

Just as he was trying to decide whether to pretend

to be sick, or simply to fall asleep over his desk, the door opened and his father's tall figure compressed itself into the van.

âG'day, Sam. Workin' you too hard, are we?' His father grinned at his sleepy face. âWhere's George?'

The governess poked her head round the radio room door. âHi, Mac. We're just finishing George's lesson here â won't be long.'

Mac nodded and looked back at Sam. âReckon you could tear yourself away from your books for a bit and come and give us a hand?'

Sam had his books away in three seconds flat and was out the door and halfway to the ute before his father had finished speaking. He perched in the open tray back not quite believing his good luck as his father and younger brother George emerged from the caravan. George grinned up at him, and clambered into the truck with a look on his face that matched Sam's. Their father gunned the engine, and they left the schoolroom behind in a cloud of dust.

âWhat's up?' George shouted into Sam's ear.

âDunno! Maybe they haven't finished the muster yet. Anyway, who cares?'

The boys clung to the railing in the back and swayed with the bumps and the jolts. Sam, at thirteen, was tall and skinny. His hair was bleached almost white by the sun, and his grey eyes often disappeared under a deep frown. Sam was a worrier. If there was anything that could ever possibly go wrong, it would. Or so he believed. He worried about schoolwork, he worried about accidents, he worried about storms and cyclones and freak asteroids hitting his family's house.

His brother George was totally the opposite. Nothing worried George, except maybe missing out on dessert. He was two years younger than Sam, and had red hair and freckles and green eyes, but without the temper that is supposed to go with them. He was shorter and stockier, and wasn't afraid of anything. When Sam was worrying about the Mir space station crashing on their house the year before, George was working out how much money he could make from selling bits as souvenirs in the event that it did hit their house.

But right now, having just escaped from a few hours of correspondence lessons, even Sam could find nothing to worry about. Their father, Mac â

short for Angus McAllister â was hurtling across the grassy flood plains in an old four-wheel drive utility towards a line of trees. George nudged Sam and pointed at a knot of men and machinery in front of the trees. They were clustered around the big red International truck which was leaning drunkenly to one side, its stock crate almost touching the ground. It was hopelessly bogged and, in trying to get out, its driver had churned the ground around the wheels into black porridge.

Three buffalo bulls were jammed together in the low side of the crate. They bleated and called mournfully as they tried to climb out from under each other, their weight adding to the task of extracting the truck. Logs had been cut and wedged under the wheels but were disappearing in the mud.

âThere's some shackles and a spanner in the glove box â grab them and bring them over here,' Mac said as he dragged a coil of wire rope from under Sam and George's feet.

They followed Mac to the truck. The other three men had parked their bullcatchers in a line in front of the stock truck, and had hooked them up to each other with tow ropes, like train carriages. Mac

shifted his own ute so that it was pointed at the cabin door of the truck, and attached the wire rope from its bullbar to the top of the stock crate.

âRight, Sam! You hop in the ute and back up until the wire rope is tight, and keep pulling backwards as we pull the truck forward. It'll jerk a bit but just keep pulling backwards.'

Sam looked extremely nervous, but did as he was told. George climbed in beside him, and they watched as the other vehicles began to strain to pull the truck forward. Sam concentrated on not stalling the engine. He could feel the ute start to buck and slip as it pulled against the cable. His knuckles turned white on the steering wheel, but he kept it going, his mouth dry and his stomach in a big knot. Suddenly the truck gave a heave and Sam's ute jerked backwards, jerked again, and was pulled sideways as the truck lurched up and forwards. Someone unhooked Sam's ute and the snake of roaring machinery dragged the big red truck to safety.

âHey, man, good one!' Sam was clapped on the back by a couple of the men as he and George trotted over to the truck, now safely on dry, hard ground.

Sam felt sick. Anything could have happened! What if he'd pulled too hard and the truck had fallen over the other way? Or if the rope had snapped and lashed back at Sam and George in the ute â they could have been dead! Or if â

âGood on you, Sam,' his father said and shook his shoulder as if he knew exactly what Sam was thinking. âNow, do I have to take you guys back to the schoolroom, or do you want to come and catch a few buffaloes?'

They spent the rest of the day clearing out a newly fenced paddock of its last feral buffalo. It had been mustered with helicopters the day before and most of the animals had been run in to the yards already. A few wily beasts had managed to escape capture but today they were being hunted down one by one. Mac and the men drove around the eight square kilometre paddock in four vehicles, scanning constantly for any sign of the quarry. Every now and then a buffalo would be sighted, and the bullcatchers would swing into action. They were modified short wheel base Toyotas â no doors, roof or windscreen â with a heavy bullbar and a mechanical contraption on the driver's side called a bionic arm.

Sam and George were riding with their father in pursuit of a big black bull. The vehicle bounced and swerved over the uneven ground, narrowly avoiding wallows and ploughing through small anthills and bushes. The buffalo was good on his feet and stayed out of reach, picking the most difficult terrain for them to follow him through. He angled and headed for the timber â once he reached the trees it would be much harder for the vehicle to keep up with him, and almost impossible to catch him in the bionic arm. Just as it looked like he would beat them, a second catcher blazed by them and cut between the trees and the bull, forcing the animal to veer back to the open plain. The bullcatcher shouldered the bull around, keeping him on a steady line as Mac moved up alongside, the bionic arm raised and his hand on the control button.

âGotcha!' yelled Sam and George, as the steel arm swung down and around the massive neck, pinning the buffalo to the side bar and slowing it down to a lumbering, protesting trot.

The two catchers pulled up and the driver of the second one, a young ringer named Marty, leapt out with a thick length of rope which he looped around

the buffalo's great black horns, deftly avoiding its attempts to hook him with one of them. The buffalo tried to shake itself free, rocking the Toyota like a leaf on a tree, but the bionic arm held it secure and finally it stood defeated, head down and sides heaving.

âNice bull, Mac! I think that's the last one of that mob. Johnno got his, and Terry's loading the other two now.'

Marty took off his cap and rubbed his head. Angus McAllister took a swig from the water bottle George passed him, and handed it over to Marty.

âThat's it, then,' Mac said. âWe've caught every buffalo we can find. You blokes take this lot back to the yards now, and the boys and I will have a last look at the Pocket before it gets dark.'

A short while later, Sam and George were speeding along a track with their father to the most easterly corner of the station. Brumby Plains was some two hundred kilometres east of Darwin, the capital of the Northern Territory, and ran from the edge of the Arnhem Land escarpment on its southern boundary to the tropical sea in the north, a distance of about forty kilometres. The Arm, as

it was called, formed the eastern boundary of the station, separating Brumby Plains from their unpleasant neighbours, the O'Dearns, more effectively than any fence. It was a high sandstone ridge that ran north from the main escarpment, like an arm pointing to the sea. The ridge was a long narrow heap of weathered sandstone, fissured and worn over millions of years into a maze of startling shapes â unsupported columns, pillars, stacks of rocks like a giant baby's building blocks, shapes that looked like heads and faces and animals. Where the Arm reached the sea, it curled back in on itself, almost enclosing a couple of hundred hectares of the flood plain like a natural paddock. It was a good hiding place for buffalo, and the grass was sweet.

They approached the entrance of the Pocket slowly, walked the last few hundred metres so as not to alert any buffalo that might be there, and climbed up the rocks near the opening. The little plain stretched out silently before them, long shadows from the surrounding walls already touching the far side of the clearing.

âDoesn't look like anything's here, Dad,' Sam whispered.

âNo, it doesn't. The helicopter definitely moved everything out yesterday. That's good. Less for us to tidy up now. Okay, guys, let's go home. I don't know about you but I'm starving!'

As they turned to leave the ridge Sam felt something roll under the sole of his boot, and glanced down. It was a dark grey, metallic looking object about six inches long, a roughly cylindrical shape with an eye at either end and a lot of scuff marks along its sides. Sam stooped to pick it up and found it was surprisingly heavy.

âLook at this, Dad. It was just here on the ground.'

His father stared at it for a second and frowned. âThat's a pretty big sinker. I wonder how it got here. No one comes here to fish that I know of.'

âThey wouldn't catch many fish up on the ridge,' said Sam.

âMaybe it fell out of the chopper yesterday,' suggested George.

Sam carried it back to the ute, still wondering, while George and his father engaged in animated discussion about what might be on for dinner. Just then they caught sight of a vehicle coming towards them in a cloud of dust.

âLooks like Jerry O'Dearn. What's he want?' muttered their father darkly. Jerry O'Dearn was the neighbour who owned the property on the eastern side of Brumby Plains. Mac scowled as the other vehicle slewed to a stop, spraying them with gravel. Sam dropped the sinker onto the floor of the ute and closed the door.

âOi, McAllister! Whatcha been up to on me boundary?' O'Dearn grunted as he climbed awkwardly out of his ute. He was a big, slovenly man with straggly hair under a dirty cap. As usual he was dressed in a blue singlet and jeans that barely did up under his huge, overhanging belly. He always smelled of stale beer and cigarettes, so Sam and George called him Stinkin' Jerry.

âAs far as I can tell, you're the one who's on someone else's land.' Mac leant against the ute with his arms folded across his chest.

âDon't play smart with me, mate. The boundary fence has been dropped and there's tyre marks all over it. Your catchers have been workin' my bottom paddock, ain't they?' Stinkin' Jerry swelled up like a big toad and his piggy eyes squinted at them.

âBetter be careful who you're accusing, O'Dearn. Stock stealing isn't what we go in for on this side of the Arm. We notified you last week, and we mustered here yesterday. You got any problems, you come up to the yard and check 'em out for yourself,' replied Mac. His eyes narrowed and his mouth formed a thin hard line.

Stinkin' Jerry looked like he wanted to say more, thought the better of it, and lurched back to his ute, hoisting up the back of his jeans as he went. As he opened the door to climb in, he looked back at them and shouted, âDon't be so sure about whose land it is, McAllister!' He laughed a nasty laugh and roared off in another shower of gravel.

âWhose land it is! Who does he think he is?' said Sam angrily.

âYeah, stupid Stinkin' Jerry!' yelled George at the rapidly disappearing vehicle.

âWhat's he talking about, Dad?' Sam asked his father.

Mac just shook his head and turned to get into the ute. Sam thought his father looked a bit pale as well as angry.

The ute headed back up the track towards the

homestead, and when the dust had settled and the engine noise had died away, two figures emerged from the bushes up on top of the ridge.

âJeez, that was close! What if they'd seen us? I told you we shouldn'ta come up here yet!' whined the smaller of the two men. He was weedy and skinny, his pale, unhealthy complexion contrasting starkly with the stringy black hair that hung limply around his pinched face. He was sweating as much from fear as from the heat of the day, and his black T-shirt clung to his back.

His companion was a big man, rough and dangerous looking, with the leathery, deeply creased skin of someone who had spent a lot of time in the bush. He narrowed his eyes at the other man.

âShut yer trap. They won't be back till after the Wet, and we'll be long gone by then,' he growled, hefting a sack onto his back as he spoke. âThis lot's gotta be set up on the waterhole before dark. Get moving.'

Â

The final weeks of school passed slowly and torturously for Sam and George as they counted down the

days to the start of the Christmas holidays. By the beginning of December most of the station work was finished. The last of the buffalo had been mustered off the flood plains into paddocks on higher ground, and the workers were leaving to spend the wet season in other places. George and Sam watched as a bright red Holden utility, laden with swags and saddles and gear and three big men squeezed into the cabin, completed a circuit of the men's quarters and drove out of the homestead yard, arms waving and horn blaring. They wandered back inside to find their mother sitting at the table, a pencil in her mouth and a faraway gaze in her eyes. She came back to earth and smiled at them.