Bully for Brontosaurus (25 page)

Read Bully for Brontosaurus Online

Authors: Stephen Jay Gould

Camper therefore decided to abandon the overarching attempts that had always devolved into nonsense and to concentrate instead on something specific that might be defined precisely—the human head.

Again he argues (incorrectly, I think, but I am explicating, not judging) that common standards exist and that, in particular, we all agree about the maximal beauty of Grecian statuary:

We will not find a single person who does not regard the head of Apollo or Venus as possessing a superior Beauty, and who does not view these heads as infinitely superior to those of the most beautiful men and women [of our day].

Since the Greek achievement involved abstraction, not portraiture, some secret knowledge must have allowed them to improve the actual human form. Camper longed to recover their rule book. He did not doubt that the great sculptures of antiquity had proceeded by mathematical formulas, not simple intuition—for proportion and harmony, geometrically expressed, were hallmarks of Greek thought. Camper would, therefore, try to infer their physical rules of ratios and angles: “It is difficult to imitate the truly sublime beauty that characterizes Antiquity until we have discovered the true physical reasons on which it was founded.”

Camper therefore devised an ingenious method of inference (also a good illustration of the primary counterintuitive principle that marks true excellence in science). When faced with a grand (but intractable) issue—like

the

definition of beauty—don’t seek the ultimate, general solution; find a corner that can be defined precisely and, as our new cliché proclaims, go for it. He decided to draw, in profile and with great precision, a range of human heads spanning nations and ages. He would then characterize these heads by various angles and ratios, trying to establish simple gradations from what we regard as least to most pleasing. He would then extrapolate this gradient in the “more pleasing” direction to construct idealized heads that exaggerate those features regarded as most beautiful in actual people. Perhaps the Greeks had sculpted their deities in the same manner.

With this background, we can grasp Camper’s own interpretation of the facial angle. Camper held that modern humans range from 70 degrees to somewhere between 80 and 90 degrees in this measure. He also made two other observations: first, that monkeys and other “brutes” maintained lower angles in proportion to their rank in the scale of nature (monkeys lower than apes, dogs lower than monkeys, and birds lower than dogs); second, that higher angles characterize smaller faces tucked below a more bulging cranium—a sign of mental nobility on the ancient theme of more is better.

Having established this range of improvement for living creatures, Camper extrapolated his facial angle in the favorable direction toward higher values.

Voilà

. He had found the secret. The beautiful skulls of antiquity had achieved their pleasing proportions by exaggerating the facial angle beyond values attained by real people. Camper could even define the distinctions that had eluded experts and made for such difficulty in attempts to copy and define. Romans, he found, preferred an angle of 95 degrees, but the ancient Greek sculptors all used 100 degrees as their ideal—and this difference explains both our ease in distinguishing Greek originals from Roman copies and our aesthetic preference for Greek statuary. (Proportion, he also argued, is always a balance between too little and too much. We cannot extrapolate the facial angle forever. At values of more than 100 degrees, a human skull begins to look displeasing and eventually monstrous—as in individuals afflicted with hydrocephalus. The peculiar genius of the Greeks, Camper argued, lay in their precise understanding of the facial angle. The great Athenian sculptors could push its value right to the edge, where maximal beauty switches to deformity. The Romans had not been so brave, and they paid the aesthetic price.)

Thus, Camper felt that he had broken the code of antiquity and offered a precise definition of beauty (at least for the human head): “What constitutes a beautiful face? I answer, a disposition of traits such that the facial line makes an angle of 100 degrees with the horizontal.” Camper had defined an abstraction, but he had worked by extrapolation from nature. He ended his treatise with pride in this achievement: “I have tried to establish on the foundation of Nature herself, the true character of Beauty in faces and heads.”

This context explains why the later use of facial angles for racist rankings represents such a departure from Camper’s convictions and concerns. To be sure, two aspects of Camper’s work could be invoked to support these later interpretations, particularly in quotes taken out of context. First, he did, and without any explicit justification, make aesthetic judgments about the relative beauty of races—never doubting that Nordic Europeans must top the scale objectively and never considering that other folks might advocate different standards. “A Lapplander,” he writes, “has always been regarded, and without exception throughout the world, as more ugly than a Persian or a Georgian.” (One wonders if anyone had ever sent a packet of questionnaires to the Scandinavian tundra; Camper, in any case at least, does not confine his accusations of ugliness to non-Caucasians.)

Second, Camper did provide an ordering of human races by facial angle—and in the usual direction of later racist rankings, with Africans at the bottom, Orientals in the middle, and Europeans on top. He also did not fail to note that this ordering placed Africans closest to apes and Europeans nearest to Greek gods. In discussing the observed range of facial angles (70 to 100 degrees in statues and actual heads), Camper notes that “It [this range] constitutes the entire gradation from the head of the Negro to the sublime beauty of the Greek of Antiquity.” Extrapolating further, Camper writes:

As the facial line moves back [for a small face tucked under bulging skull] I produce a head of Antiquity; as I bring it forward [for a larger, projecting face] I produce the head of a Negro. If I bring it still further forward, the head of a monkey results, more forward still, and I get a dog, and finally a woodcock; this, now, is the primary basis of my edifice.

(Our deprecations never cease. The French word for woodcock—

bécasse

—also refers to a stupid woman in modern French slang.)

I will not defend Camper’s view of human variation any more than I would pillory Lincoln for racism or Darwin for sexism (though both are guilty by modern standards). Camper lived in a different world, and we cannot single him out for judgment when he idly repeats the commonplaces of his age (nor, in general, may we evaluate the past by the present, if we hope to understand our forebears).

Camper’s comments on racial rankings are fleeting and stated

en passant

. He makes no major point of African distinctions except to suggest that artists might now render the black Magus correctly in painting the Epiphany. He does not harp upon differences among human groups and entirely avoids the favorite theme of all later writings in craniometric racism—finer scale distinctions between “inferior” and “superior” Europeans. His text contains not a whiff or hint of any suggestion that low facial angles imply anything about moral worth or intellect. He charges Africans with nothing but maximal departure from ideal beauty. Moreover, and most important, Camper’s clearly stated views on the nature of human variability preclude, necessarily and a priori, any equation of difference with innate inferiority. This is the key point that later commentators have missed because we have lost Camper’s world view and cannot interpret his text without recovering the larger structure of his ideas.

We now live in a Darwinian world of variation, shadings, and continuity. For us, variation among human groups is fundamental, both as an intrinsic property of nature and as a potential substratum for more substantial change. We see no difference in principle between variation within a species and established differences between species—for one can become the other via natural selection. Given this potential continuity, both kinds of variation may record an underlying and basically similar genetic inheritance. To us, therefore, linear rankings (like Camper’s for the facial angle) quite properly smack of racism.

But Camper dwelt in the pre-Darwinian world of typology. Species were fixed and created entities. Differences among species recorded their fundamental natures. But variation within a species could only be viewed as a series of reversible “accidents” (departures from a species’ essence) imposed by a variety of factors, including climate, food, habits, or direct manipulation. If all humans represented but a single species, then our variation could only be superficial and accidental in this Platonic sense. Physical differences could not be tokens of innate inferiority. (By “accidental,” Camper and his contemporaries did not mean capricious or devoid of immediate import in heredity. They knew that black parents had black children. Rather, they argued that these traits, impressed into heredity by climate or food, had no fixed status and could be easily modified by new conditions of life. They were often wrong, of course, but that’s not the point.)

Therefore, to understand Camper’s views about human variability, we must first learn whether he regarded all humans as members of one species or as products of several separate creations (a popular position known at the time as polygeny). Camper recognized these terms of the argument and came down strongly and incisively for human unity as a single species (monogeny). In designating races by the technical term “variety,” Camper used the jargon of his day to underscore his conviction that our differences are accidental and imposed departures from an essence shared by all; our races are not separated by differences fixed in heredity. “Blacks, mulattos, and whites are not diverse species of men, but only varieties of the human species. Our skin is constituted exactly like that of the colored nations; we are therefore only less black than they.” We cannot even know, Camper adds, whether Adam and Eve were created white or black since transitions between superficial varieties can occur so easily (an attack on those who viewed blacks as degenerate and Adam and Eve as necessarily created in Caucasian perfection):

Whether Adam and Eve were created white or black is an entirely indifferent issue without consequences, since the passage from white to black, considerable though it be, operates as easily as that from black to white.

Misinterpretation may be more common than accuracy, but a misreading precisely opposite to an author’s true intent may still excite our interest for its sheer perversity. When, in order to grasp this inversion, we must stretch our minds and learn to understand some fossil systems of thinking, then we may convert a simple correction to a generality worthy of note. Poor Petrus Camper. He became the semiofficial grandpappy of the quantitative approach to scientific racism, yet his own concept of human variability precluded judgments about innate worth a priori. He developed a measure later used to make invidious distinctions among actual groups of people, but he pressed his own invention to the service of abstract beauty. He became a villain of science when he tried to establish criteria for art. Camper got a bad posthumous shake on earth; I only hope that he met the right deity on high (facial angle of 100 degrees, naturally), the God of Isaiah, who also equated beauty with number and proportion—he “who hath measured the waters in the hollow of his hand, and meted out heaven with the span.”

EVERY PROFESSION

has its version: Some speak of “Sod’s law” others of “Murphy’s law.” The formulations vary, but all make the same point—if anything bad can happen, it will. Such universality of attribution can only arise for one reason—the principle is true (even though we know that it isn’t).

The fieldworker’s version is simply stated: You always find the most interesting specimens at the very last moment, just when you absolutely must leave. The effect of this phenomenon can easily be quantified. It operates weakly for localities near home and easily revisited and ever more strongly for distant and exotic regions requiring great effort and expense for future expeditions. Everyone has experienced this law of nature. I once spent two weeks on Great Abaco, visiting every nook and cranny of the island and assiduously proving that two supposed species of

Cerion

(my favorite land snail) really belonged to one variable group. On the last morning, as the plane began to load, we drove to the only unexamined place, an isolated corner of the island with the improbable name Hole-in-the-Wall. There we found hundreds of large white snails, members of the second species.

Each profession treasures a classic, or canonical, version of the basic story. The paleontological “standard,” known to all my colleagues as a favorite campfire tale and anecdote for introductory classes, achieves its top billing by joining the most famous geologist of his era with the most important fossils of any time. The story, I have just discovered, is also entirely false (more than a bit embarrassing since I cited the usual version to begin an earlier essay in this series).

Charles Doolittle Walcott (1850–1927) was both the world’s leading expert on Cambrian rocks and fossils (the crucial time for the initial flowering of multicellular life) and the most powerful scientific administrator in America. Walcott, who knew every president from Teddy Roosevelt to Calvin Coolidge, and who persuaded Andrew Carnegie to establish the Carnegie Institute of Washington, had little formal education and began his career as a fieldworker for the United States Geological Survey. He rose to chief, and resigned in 1907 to become secretary (their name for boss) of the Smithsonian Institution. Walcott had his finger, more accurately his fist, in every important scientific pot in Washington.

Walcott loved the Canadian Rockies and, continuing well into his seventies, spent nearly every summer in tents and on horseback, collecting fossils and indulging his favorite hobby of panoramic photography. In 1909, Walcott made his greatest discovery in Middle Cambrian rocks exposed on the western flank of the ridge connecting Mount Field and Mount Wapta in eastern British Columbia.

The fossil record is, almost exclusively, a tale told by the hard parts of organisms. Soft anatomy quickly disaggregates and decays, leaving bones and shells behind. For two basic reasons, we cannot gain an adequate appreciation for the full range of ancient life from these usual remains. First, most organisms contain no hard parts at all, and we miss them entirely. Second, hard parts, especially superficial coverings, often tell us very little about the animal within or underneath. What could you learn about the anatomy of a snail from the shell alone?

Paleontologists therefore treasure the exceedingly rare soft-bodied faunas occasionally preserved when a series of unusual circumstances coincide—rapid burial, oxygen-free environments devoid of bacteria or scavengers, and little subsequent disturbance of sediments.

Walcott’s 1909 discovery—called the Burgess Shale—surpasses all others in significance because he found an exquisite fauna of soft-bodied organisms from the most crucial of all times. About 570 million years ago, virtually all modern phyla of animals made their first appearance in an episode called “the Cambrian explosion” to honor its geological rapidity. The Burgess Shale dates from a time just afterward and offers our only insight into the true range of diversity generated by this most prolific of all evolutionary events.

Walcott, committed to a conventional view of slow and steady progress in increasing complexity and diversity, completely misinterpreted the Burgess animals. He shoehorned them all into modern groups, interpreting the entire fauna as a set of simpler precursors for later forms. A comprehensive restudy during the past twenty years has inverted Walcott’s view and taught us the most surprising thing we know about the history of life: The fossils from this one small quarry in British Columbia exceed, in anatomical diversity, all modern organisms in the world’s oceans today. Some fifteen to twenty Burgess creatures cannot be placed into any modern phylum and represent unique forms of life, failed experiments in metazoan design. Within known groups, the Burgess range far exceeds what prevails today. Taxonomists have described almost a million living species of arthropods, but all can be placed into three great groups—insects and their relatives, spiders and their kin, and crustaceans. In Walcott’s single Canadian quarry, vastly fewer species include about twenty more basic anatomical designs! The history of life is a tale of decimation and later stabilization of few surviving anatomies, not a story of steady expansion and progress.

But this is another story for another time (see my book

Wonderful Life

, 1989). I provide this epitome only to emphasize the context for paleontology’s classic instance of Sod’s law. These are no ordinary fossils, and their discoverer was no ordinary man.

I can provide no better narration for the usual version than the basic source itself—the obituary notice for Walcott published by his longtime friend and former research assistant Charles Schuchert, professor of paleontology at Yale. (Schuchert was, by then, the most powerful paleontologist in America, and Yale became the leading center of training for academic paleontology. The same story is told far and wide in basically similar versions, but I suspect that Schuchert was the primary source for canonization and spread. I first learned the tale from my thesis adviser, Norman D. Newell. He heard it from his adviser, Carl Dunbar, also at Yale, who got it directly from Schuchert.) Schuchert wrote in 1928:

One of the most striking of Walcott’s faunal discoveries came at the end of the field season of 1909, when Mrs. Walcott’s horse slid in going down the trail and turned up a slab that at once attracted her husband’s attention. Here was a great treasure—wholly strange Crustacea of Middle Cambrian time—but where in the mountain was the mother rock from which the slab had come? Snow was even then falling, and the solving of the riddle had to be left to another season, but next year the Walcotts were back again on Mount Wapta, and eventually the slab was traced to a layer of shale—later called the Burgess shale—3,000 feet above the town of Field, British Columbia, and 8,000 feet above the sea.

Stories are subject to a kind of natural selection. As they propagate in the retelling and mutate by embellishment, most eventually fall by the wayside to extinction from public consciousness. The few survivors hang tough because they speak to deeper themes that stir our souls or tickle our funnybones. The Burgess legend is a particularly good story because it moves from tension to resolution, and enfolds within its basically simple structure two of the greatest themes in conventional narration—serendipity and industry leading to its just reward. We would never have known about the Burgess if Mrs. Walcott’s horse hadn’t slipped going downslope on the very last day of the field season (as night descended and snow fell, to provide a dramatic backdrop of last-minute chanciness). So Walcott bides his time for a year in considerable anxiety. But he is a good geologist and knows how to find his quarry (literally in this case). He returns the next summer and finally locates the Burgess Shale by hard work and geological skill. He starts with the dislodged block and traces it patiently upslope until he finds the mother lode. Schuchert doesn’t mention a time, but most versions state that Walcott spent a week or more trying to locate the source. Walcott’s son Sidney, reminiscing sixty years later, wrote in 1971: “We worked our way up, trying to find the bed of rock from which our original find had been dislodged. A week later and some 750 feet higher we decided that we had found the site.”

I can imagine two basic reasons for the survival and propagation of this canonical story. First, it is simply too good a tale to pass into oblivion. When both good luck and honest labor combine to produce victory, we all feel grateful to discover that fortune occasionally smiles, and uplifted to learn that effort brings reward. Second, the story might be true. And if dramatic and factual value actually coincide, then we have a real winner.

I had always grasped the drama and never doubted the veracity (the story is plausible, after all). But in 1988, while spending several days in the Walcott archives at the Smithsonian Institution, I discovered that all key points of the story are false. I found that some of my colleagues had also tracked down the smoking gun before me, for the relevant pages of Walcott’s diary had been earmarked and photographed before.

Walcott, the great conservative administrator, left a precious gift to future historians by his assiduous recordkeeping. He never missed a day of writing in his diary. Even at the very worst moment of his life, July 11, 1911, he made the following, crisply factual entry about his wife: “Helena killed at Bridgeport Conn. by train being smashed up at 2:30

A.M.

Did not hear of it until 3

P.M.

Left for Bridgeport 5:35

P.M.

” (Walcott was meticulous, but please do not think him callous. Overcome with grief the next day, he wrote on July 12: “My love—my wife—my comrade for 24 years. I thank God I had her for that time. Her untimely fate I cannot now understand.”)

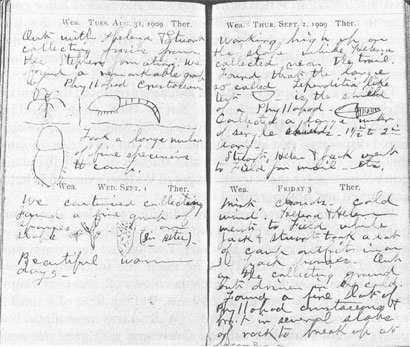

Walcott’s diary for the close of the 1909 field season neatly dismisses part one of the canonical tale. Walcott found the first soft-bodied fossils on Burgess ridge either on August 30 or 31. His entry for August 30 reads:

Out collecting on the Stephen formation [the unit that includes what Walcott later called the Burgess Shale] all day. Found many interesting fossils on the west slope of the ridge between Mounts Field and Wapta [the right locality for the Burgess Shale]. Helena, Helen, Arthur, and Stuart [his wife, daughter, assistant, and son] came up with remainder of outfit at 4

P.M.

On the next day, they had clearly discovered a rich assemblage of soft-bodied fossils. Walcott’s quick sketches (see figure) are so clear that I can identify the three genera he depicts

—Marrella

(upper left), the most common Burgess fossil and one of the unique arthropods beyond the range of modern designs;

Waptia

, a bivalved arthropod (upper right); and the peculiar trilobite

Naraoia

(lower left). Walcott wrote: “Out with Helena and Stuart collecting fossils from the Stephen formation. We found a remarkable group of Phyllopod crustaceans. Took a large number of fine specimens to camp.”

The smoking gun for exploding a Burgess Shale legend. Walcott’s diary for the end of August and the beginning of September, 1909. He collected for an entire week in good weather.

SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION

.

What about the horse slipping and the snow falling? If this incident occurred at all, we must mark the date as August 30, when Walcott’s family came up the slope to meet him in the late afternoon. They might have turned up the slab as they descended for the night, returning the next morning to find the specimens that Walcott drew on August 31. This reconstruction gains some support from a letter that Walcott wrote to Marr (for whom he later named the “lace crab”

Marrella

) in October 1909:

When we were collecting from the Middle Cambrian, a stray slab of shale brought down by a snow slide showed a fine Phyllopod crustacean on a broken edge. Mrs. W. and I worked on that slab from 8 in the morning until 6 in the evening and took back with us the finest collection of Phyllopod crustaceans that I have ever seen.

(Phyllopod, or “leaf-footed,” is an old name for marine arthropods with rows of lacy gills, often used for swimming, on one branch of their legs.)

Transformation can be subtle. A snow slide becomes a snowstorm, and the night before a happy day in the field becomes a forced and hurried end to an entire season. But far more important, Walcott’s field season did not finish with the discoveries of August 30 and 31. The party remained on Burgess ridge until September 7! Walcott was thrilled by his discovery and collected with avidity every day thereafter. The diaries breathe not a single word about snow, and Walcott assiduously reported the weather in every entry. His happy week brought nothing but praise for Mother Nature. On September 1 he wrote: “Beautiful warm days.”

Finally, I strongly suspect that Walcott located the source for his stray block during the last week of his 1909 field season—at least the basic area of outcrop, if not the very richest layers. On September 1, the day after he drew the three arthropods, Walcott wrote: “We continued collecting. Found a fine group of sponges on slope (

in situ

) [meaning undisturbed and in their original position].” Sponges, containing some hard parts, extend beyond the richest layers of soft-bodied preservation, but the best specimens come from the strata of the Burgess mother lode. On each subsequent day, Walcott found abundant soft-bodied specimens, and his descriptions do not read like the work of a man encountering a lucky stray block here and there. On September 2, he discovers that the supposed shell of an ostracode really houses the body of a Phyllopod: “Working high up on the slope while Helena collected near the trail. Found that the large so-called Leperditia-like test is the shield of a Phyllopod.” The Burgess quarry is “high up on the slope,” while stray blocks would slide down toward the trail.