Capitol Men (23 page)

Authors: Philip Dray

The rise of the Liberal Republicans promised to make the election of 1872 the first, since the inception of the party a generation before, characterized by splits and oppositions among party members, which rendered Sumner's assaults on Grant all the more dangerous. As Sydney Howard Gay, a black New Yorker, reminded Sumner, "We believe, as Frederick Douglass has said, that 'The Republican Party is the deck; all the rest is the sea.' We do not propose to go overboard. We have been drifting astern of civilization, hanging on by a rope, for several generations, and have had enough of it." Discussing the president's alleged offenses, Gay offered that they were "infinitely small when weighed against his services to the Republic and to my race," adding, "The

nepotism

which assumes such formidable dimensions in your eyes seems in

ours a small blemish when we remember the cruel

despotism

from which this man was the chosen instrument to deliver us."

South Carolina's black congressman Robert Brown Elliott, in an address honoring the tenth anniversary of emancipation in the District of Columbia, seemed to pick up on Gay's theme, warning that the Republicans could not afford the luxury of overconfidence. Speaking on the historical precariousness of social and political progress, he cautioned against faith in the belief that "revolutions never go backward." The Jews, he explained, were led from Egypt after 430 years of slavery, but within a few generations they were enslaved again by the Assyrians and Babylonians. The French staged a noble revolution, but it devoured them, so that they again had an emperor. The Declaration of Independence had vowed all men were created equal, but only eleven years later the Constitution preserved the concept of men as property. Thus, Elliott said, "It will be seen that we hold our rights by no perpetual or irrevocable charter. They are confronted by constant hazards. The enemies of the ancient Israelites, the Egyptian monarch, with his multitude of horsemen and chariots, were buried in the waters of the Red Sea, while our foes have crossed with us. Yet, perhaps by the inscrutable order of Providence, the very dangers that menace our rights are intended to admonish us to be vigilant in guarding them."

Sumner, however, proved impervious to all counsel and advice and broke with the traditional Republican Party to endorse for president the Liberal Republican candidate Horace Greeley, editor of the

New York Tribune.

As many had feared, Greeley's candidacy was also backed by the Democrats, who had not bothered to nominate a candidate of their own. A bookish, awkward-looking man with huge white whiskers and a "big round face of infantile mildness," Greeley was an unlikely choice for high office, and Sumner's endorsement only further rankled and confused the Republican faithful. Greeley had supported emancipation and was friendly to the plight of the freedmen, but his views were eccentric; he had at various times been a booster for socialism, feminism, spiritualism, and vegetarianism, and was hardly a longtime abolitionist, as Sumner now claimed. "I need not tell you, my friends, what Horace Greeley is," Wendell Phillips assured Boston's African American community. "A trimmer by nature and purpose, he has abused even an American politician's privilege of trading principles for success ... You and I know well when

abolitionist

was a term of reproach how timidly he held up his skirts about him, careful to put a wide distance between himself and us."

The doubts about Greeley soon were reflected in the difficult fusion of Liberal Republicans and Southern Democrats. There was no real cohesion between the two factions, no plan to win a unified campaign. The Liberals were motivated primarily by their anger with Grant over spoils, corruption, the Ku Klux Klan Act, and Santo Domingo, and the Democrats by the desire to reassert states' rights. Nor did Greeley lose any time in demonstrating his unsuitability as a candidate. In a speaking tour that swept through New England, the eastern seaboard, and the Midwest, he appeared disorganized, wandered off topic, shuffled his papers, became defensive when challenged, and overall cut a poor figure. The demanding schedule of the tourâat one point he made twenty-two speeches in a single dayâno doubt also took a toll on the sixty-two-year-old candidate. By the time he limped back to the relative safety of New York, the nation's press was comparing the experience to Andy Johnson's dismal "Swing Around the Circle" of 1866 and praising President Grant as statesmanlike for wisely staying off the campaign trail.

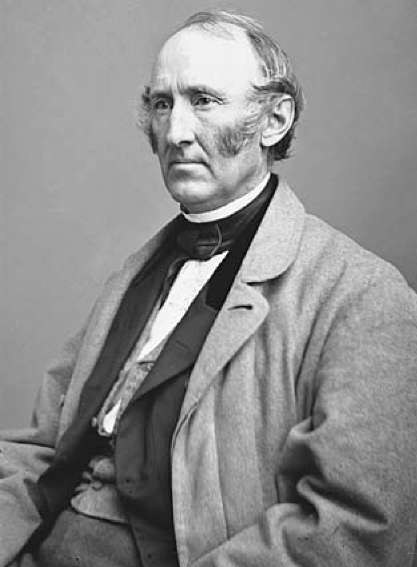

WENDELL PHILLIPS

Among the allies Grant had retained, few proved as valuable as the cartoonist for

Harper's Weekly.

After the election of 1868, Grant had credited his victory in part to "the pencil of Thomas Nast," but it was the 1872 contest that saw Nast at the height of his influence on national politics. The artist had deeply admired Abraham Lincoln, but he idolized Grant, whom he saw as a homespun American version of the Italian patriot general Giuseppe Garibaldi, whose insurrectionary campaigns across Italy Nast had covered as a young artist and reporter. The Liberal Republicans, on the other hand, he viewed as betrayers of the war's great sacrifice, and Greeley's exhortation to his Southern Democrat partners that the war's former adversaries "Clasp Hands over the Bloody Chasm" was, in Nast's view, infamous. In a series of cartoons lampooning the slogan, Nast showed Greeley physically propping up a badly wounded freedman and encouraging him to accept the greeting

of a white desperado standing on the other side of a pile of black corpses; another depicted the editor extending his hand southward over the graves of the thirteen thousand Union soldiers who had perished at Andersonville.

Nast's other caricatures of the campaign itself were equally devastating: Schurz as a demented pianist-composer writing the same piece over and over; Sumner as a Roman senator breaking his bow as he tries to shoot one last arrow; Columbia using the shield of Truth to protect Grant from Liberal arrows. Nast at one point depicted Greeley as a Ku Klux Klansman, and not having an image handy of Greeley's running mate, the little-known Missouri governor B. Gratz Brown, drew him as a label stuck to Greeley's jacket, reading "...and Gratz Brown," perfectly lampooning Brown's insignificance and the general hopelessness of the ticket. Another cartoon presented a comatose Greeley being carried on a hospital litter, with the caption "We are on the Home Stretch." So deadly were Nast's efforts throughout the campaign that

Leslie's Illustrated,

a competitor of

Harper's,

sent abroad for a renowned cartoonist from London to possibly counter him; but the effort was futile. Horace Greeley was a target who only seemed to grow larger, Thomas Nast was at the top of his game, and it appeared certain that Ulysses'S. Grant, "the Man on Horseback," would continue to ride in command.

In his new role as the lieutenant governor of Louisiana, Pinchback embarked on a speaking tour of his own that summer of 1872, visiting Maine on behalf of the Republican congressman James Blaine, who was up for reelection. It was a way for Pinchback to shore up his recognition and support among national Republicans and a chance for the party to show off one of its rising Southern stars at a time when confidence in Southern Republicanism was desperately needed. But the journey led to one of the strangest cloak-and-dagger escapades in American political history, and rather than demonstrate Pinchback's readiness for the national political stage, it revealed his provincialism.

At home in Louisiana, where both the national and state campaigns were competitive, Pinchback supported President Grant's reelection, breaking with Warmoth, who aligned himself with the Liberal Republican-Democratic ticket. This brought a sudden thaw in Pinchback's relations with the Grant-oriented Customhouse faction; the state Republican convention even offered to place his name in nomination for governor. Pinchback declined, pointing out that a black gubernatorial candidate on the ballot would only scare more white Republicans into

the camp of Horace Greeley. The Republicans ultimately settled on a state ticket of William Pitt Kellogg for governor, C. C. Antoine for lieutenant governor, and Pinchback for congressman at large.

On his way back from New England, Pinchback stopped in New York City, staying at the popular Fifth Avenue Hotel, headquarters of the Republican National Committee and a favorite political gathering place where President Grant was known to keep a suite of rooms. To his surprise, Pinchback learned that one of his fellow guests was none other than Governor Warmoth, who invited his lieutenant to join him in his room that night for a late supper. Pinchback agreed, then went to meet vice presidential candidate Henry Wilson of Massachusetts, who at the Republican national convention in June had been nominated to replace Schuyler Colfax, and William E. Chandler, secretary of the Republican National Committee. When Chandler asked what the party's chances were of carrying Louisiana, Pinchback confessed they were poor. He explained that because of his state's archaic election laws, the voting process could easily be abused, almost certainly resulting in diminished black voter turnout and fewer votes recorded for Grant. So harmful were the regulations, Pinchback said, that the state legislature had recently passed new laws to reform the process and make it more difficult to commit election fraud; Warmoth, however, had refused to sign the reforms into law.

Listening to Pinchback's explanation, Chandler suddenly had an idea: since Warmoth was planning to tarry in New York awhile, and Pinchback was headed home, what if Pinchback were to hurry back to Louisiana and, invoking his status as acting governor while Warmoth was out of the state, sign the election reform bills into law? Wilson and Chandler emphasized that Louisiana's eight electoral votes might be key to a Republican victory for the national ticket and that it would be a "grand thing" if Pinchback were to undertake such a mission. The ambitious Pinchback instantly recognized an opportunity to play hero to both the party leadership and President Grant. "If the success of the Republican party is at stake, I dare do anything that will save it," declared Pinchback, and agreed to start for Louisiana at once. There was a small technicality, howeverâthe promise Pinchback had made earlier to have dinner with Warmoth. To avoid leading the governor to suspect that his lieutenant governor had left town, Pinchback parked his trunk, with his name written on it, outside his hotel room. If Warmoth passed by, he would assume that Pinchback was still in the city and had simply become distracted and forgotten their dinner arrangement.

At first the plan worked. Pinchback failed to appear at Warmoth's room, but Warmoth thought little of it and went to bed, figuring his dinner guest had found something more entertaining to do in the big city. Pinchback had conspired with his friend Henry Corbin, the editor of the

Louisianian,

to seek out Warmoth the next day and make his apologies, explaining that Pinchback had been called away at the last minute to give a speech. But Warmoth, upon going downstairs the next morning, encountered not Corbin but another of Pinchback's friends, A. B. Harris, a state senator from Louisiana. Pinchback had lacked the time to let Harris in on the scheme, and when Warmoth inquired after Pinchback, Harris replied that he had not seen him since the prior afternoon. Warmoth, thinking this information a bit odd, thanked him and walked away.

Pinchback, meanwhile, having left New York by the first train available, had gone to Pittsburgh, then on to Cincinnati, and encountered an exasperating six-hour layover at each stop. The only consolation was that he had not heard from William Chandler back in New York, who had promised to telegraph immediately if Warmoth was seen starting toward Louisiana. Exhausted already from the trip, but fairly confident that Warmoth was not on his trail, Pinchback at last boarded a train for New Orleans, nestled into a comfortable berth, and went to sleep.

Several hours and many miles later he was awakened by someone shining a light in his eyes. "Are you Governor Pinchback?" a voice asked.

"I am that man."

"Then I am directed to inform you that there is a telegram awaiting you in the telegraph office, which the operator is directed to deliver only to you in person."

"Where are we?" Pinchback asked.

"Canton, Mississippi."

Sure that this would be a message from Chandler, Pinchback threw on some clothes and hurried off the train and into the tiny office. Once inside, it seemed to take a very long time for the operator to locate the envelope bearing the telegram. When he finally handed it over, Pinchback opened it, but there was nothing inside except a blank piece of paper. Pinchback, confused and still not fully awake, was struggling to make sense of the situation when he realized that, outside, his train was starting to move. At that moment, as one New Orleans newspaper related, "the consciousness flashed upon the sagacious Pinch that he was sold." He leapt to the office door and found it locked; he rushed to a window and tried to yank it open, but it also was closed tight. Returning

to the door, he banged on it loudly enough to attract the attention of someone on the platform, but by the time he was released, the red lanterns on the rear of his train were vanishing around a bend, a quarter-mile away.