Capitol Men (63 page)

Authors: Philip Dray

Civil rights workers soon discovered that Reconstruction had left behind not only a constitutional blueprint of sorts but also some very useful tools. Its commitment to black education and equal rights was echoed in the NAACP Legal Defense Fund's breakthrough in

Brown.

The founding in the 1860s of black colleges such as Alcorn, the Hampton Institute, and Fisk, as well as the political empowerment of the black church, largely provided the modern movement's initial intellectual and spiritual energy as well as its legions of youthful foot soldiers. The language and even some of the tactics of the struggle surrounding the Civil Rights Act of 1875 returned to life in the Montgomery boycott and in the lunch counter sit-in movement that flowered in North Carolina in the early spring of 1960; that movement became, overnight, a national phenomenon as masses of young protesters integrated restaurants, department stores, and even public swimming pools. The next year CORE activists known as Freedom Riders broke down segregation on interstate bus lines. Resistance was strong and often bloody, and the jailing and beating of civil rights "agitators" frequent. The steadfastedness of the activists, however, abetted by public support, a largely sympathetic national media, and eventual congressional and Justice Department action, combined ultimately to break the Southern opposition.

Voting rights guaranteed by the Fifteenth Amendment and the Enforcement Acts provided a basis for the voter registration campaigns that swept Mississippi and Alabama in the 1960s, as young workers from the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) fanned out across rural hamlets where the nefarious "understanding clause" of late-nineteenth-century origin, and various other impediments, still kept would-be voters from the polls. In many areas black voting had become so depressed over the years that it existed only in historical memory; civil rights volunteers met longtime residents of the Black Belt who were unsure what the term even meant.

SNCC workers encouraged and helped educate black residents to appear before the registrars who had long intimidated them. At one point an SNCC researcher discovered an obscure Mississippi law dating from Reconstruction, originally meant to protect disenfranchised Confederates, that allowed for "unacceptable" votes to be tallied as a protest in the hope of being considered at a later time. The inspired result was the Mississippi Freedom Vote of 1963, in which civil rights workers held a mock election of disenfranchised blacks, calling the nation's attention to the injustice of Southern suffrage laws and laying the groundwork for the Freedom Summer of 1964. A federal reaffirmation of Americans' un-hindered right to the franchise arrived with the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which did away with the "understanding clause," poll taxes, and other longstanding schemes of disenfranchisement.

Perhaps the most striking example of Reconstruction measures being revived for modern purposes involved the Enforcement Acts. When concerted NAACP efforts at securing a federal anti-lynching law died in Congress in the two decades after World War I, the Justice Department's newly created Civil Rights Division began considering other means of challenging racial violence, including the use of long-dormant anti-Klan conspiracy laws. By prohibiting mob violence carried out in concert with the police, or "under color of law," the laws once aimed at the Reconstruction Klan, government attorneys believed, could be adapted to prosecute contemporary lynchings and murders. Unfortunately, getting Southern federal judges and grand juries to cooperate proved difficult, and the Justice Department brought several such cases before finally, in the 1960s, working closely with the FBI, it won its first convictions against Southern terrorists. The most notable courtroom

victories were related to the 1964 Klan-and-police conspiracy killings of the civil rights workers Andrew Goodman, Michael Schwerner, and James Chaney in Mississippi and the shooting death of Viola Liuzzo, a white Northern woman murdered while assisting in the March on Selma in 1965.

Reconstruction, after slumbering for decades in the attic of American history, was thus able to play a key, if belated, role in dragging the old Confederacy into the twentieth century. The fortresslike mindset the region had developed in response to emancipation and Reconstruction, and the warped antics of segregation's modern defenders, crude figures such as the Birmingham police commissioner Eugene "Bull" Connor and the Mississippi governor Ross Barnett, appeared particularly base and anachronistic when exposed in the glare of network news cameras or in the pages of

Life

magazine. Their white-supremacist ranting and demagoguery, and tactics such as siccing police dogs and playing fire hoses on black citizens, contrasted starkly with the moral decency of the civil rights cause itself.

Of course, as in the first Reconstruction, not all was smooth sailing. Some changesâdesegregation in restaurants, in hotels, and on busesâcame fairly readily; some, such as voting rights, required years of determined effort; others proved more or less intractable. Despite the victory over segregation and the passage of new laws such as the Civil Rights Act of 1964, there remained a painful gap between white and black Americans in income, employment, education, and housingâproblems not easily remedied. And in another echo of Reconstruction, the ensuing frustration among reformers undercut the movement's idealism, and by 1966 dissent rankled among civil rights workers; some threw their support behind Black Nationalism. Martin Luther King Jr. and other leaders were led to rethink their strategies and begin addressing poverty and labor issues at the grassroots level.

While no one can question the overwhelming success of the civil rights movement or doubt the ways in which it irrevocably transformed America, its legacy, like that of Reconstruction, has also involved a conservative backlash. Politically, since the late 1960s, conservative forces have played skillfully upon Southern whites' traditional views on racial matters to solidify electoral support across the region. Nationwide, forced school desegregation (busing), preferences in employment and education (affirmative action), and welfare have all undergone judicial and legislative retrenchment, while fundamental challenges such as economic disparity between the races, inequality of opportunity,

and bias in America's systems of justice and law enforcement continue unresolved.

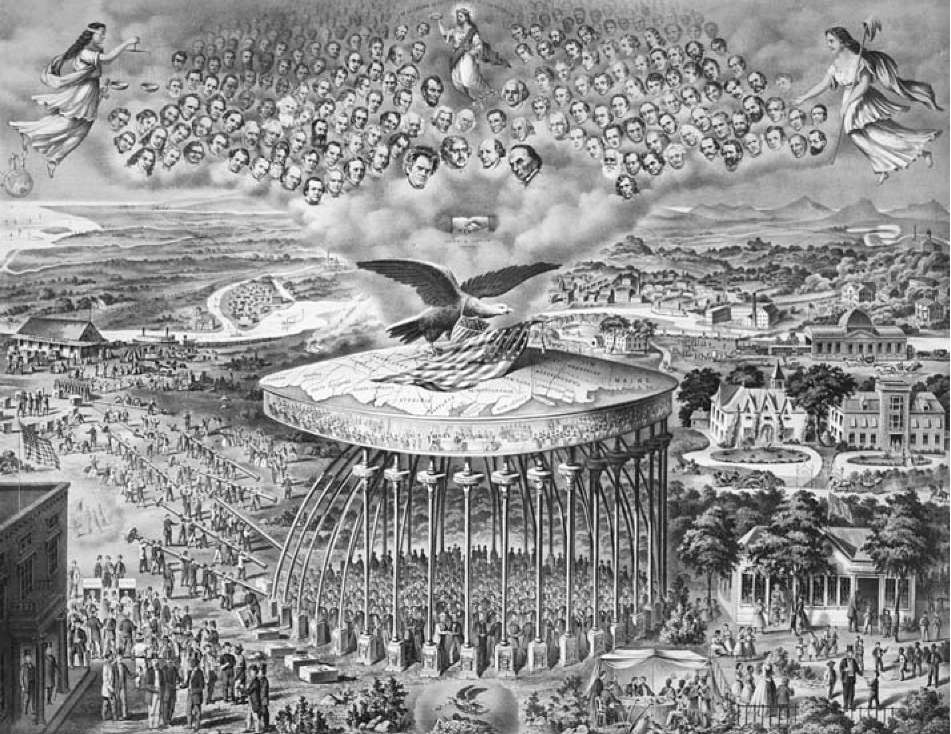

One of the most dramatic allegorical images of Reconstruction America is captured in the 1867 Horatio Bateman lithograph of the republic as a giant pavilion being renovated. Against a background of men and women mingling in peaceful village squares and along city streets, the pavilion's timbers of

SLAVERY

are carted away, to be replaced by new ones representing

JUSTICE, DEMOCRACY,

and

GOOD GOVERNMENT;

overhead a cloud of spirits includes Lincoln, Washington, Webster, and Calhoun, all of them gazing down with approval.

HORATIO BATEMAN'S RECONSTRUCTION LITHOGRAPH

When the actual edifice of Reconstruction fell, however, the hovering angels of the country's destiny hurriedly disappeared, leaving the mortals below to make good their own escape. Franklin Moses Jr., the "Robber Governor" who had raised the Confederate flag over Fort Sumter but then disgracefully used the South Carolina treasury to pay off his horseracing debts, became a drug addict and later went north to peddle sordid "inside" tales of Southern Reconstruction to big-city newspapers; his actions so mortified his family that they changed their name. Three of Daniel Chamberlain's children had perished by 1887 when his wife, Alice, died, leaving him the sole parent to his young son Waldo, who succumbed to illness in 1902 at the age of sixteen. Vanquished and alone, Chamberlain, who suffered from ailments he linked to his stressful years as governor of South Carolina, spent his remaining years traveling in an elusive search for health, and died in Charlottesville, Virginia, in 1907. Henry Clay Warmoth, the carpetbagger governor of Louisiana who, despite having been born in Illinois, always claimed that he was at heart a Southerner, remained in his adopted state to operate a successful sugar plantation.

Adelbert Ames enjoyed careers as a flour mill owner in Minnesota and a textile mill operator in Massachusetts, while dabbling in numerous inventions, such as pencil sharpeners and extension ladders for fire engines. He returned to military service in the Spanish-American War and retired, a wealthy man, to Florida, where he golfed with John D. Rockefeller and became known, thanks to his longevity, as "the Last General of the Civil War." He died in 1933 at age ninety-seven. Although Ames made many friends among ex-Confederates over the years, his memory was not entirely dear to Mississippians; in 1958 Henry M. "Doc" Fraser, a Dixiecrat who had led the state's walkout from the 1948 national Democratic convention, launched a movement to have Ames's official portrait removed from the capitol in Jackson. "Are the portraits of Hitler, Mussolini, Joe Stalin and others of their ilk hanging in the capitol building in Washington?" Fraser demanded. Governor J. P. Coleman insisted that Ames's portrait remain on display, although he stressed to newsmen that the place where it and other governors' images could be viewed was not a "hall of fame."

Most of the black national political figures of the generation of 1868 had disappeared with far less recognition. Hiram Revels collapsed and died during a church meeting in Aberdeen, Mississippi, in 1901. Joseph Rainey worked as a federal tax agent in Charleston until 1881, failed in business, then fell into poor health and died in 1887. Today his name graces a waterside park in his native Georgetown, South Carolina. The former congressman Alonzo Ransier, who had spoken so eloquently of education's role in sustaining a republican form of government, and who once famously got the better of a white antagonist on the floor of the House of Representatives, worked as a street cleaner in Charleston until his death in 1882. A story was told that Ransier one day found in the gutter an old newspaper that contained an article about him from

the long-ago heyday of his political career. "Hardly can it be supposed that he was without emotion as he crumpled the vagrant sheet, and tossing it into the dust cart went on humbly with his street-cleaning task."

Ransier's journey to obscurity was not unique. The diners at the Jefferson Club, an elite Washington restaurant in the late 1890s, would have been surprised to learn that the courtly black waiter who filled their water glasses, Richard H. Gleaves, had once been the lieutenant governor of South Carolina. He worked as a server at the restaurant, within sight of the U.S. Capitol, until his death in 1907.

Others survived by securing patronage jobs from the Republican Party. In the case of Blanche K. Bruce, the expectation of reward was particularly high; his favor to Garfield at the 1880 Republican National Convention had not been forgotten, and his term in the Senate ended just as Garfield became president in early 1881. Bruce was offered a post as minister to Brazil or a high-ranking position in the post office, both of which he rejected, asking instead to be appointed register of the treasury. Garfield hesitated, telling Bruce that he feared white women in the Treasury Department might resent working under him. Irritated by Garfield's prevarication, Bruce, according to one account, told other Republicans he would "give the story to the country" if so shabby an excuse for denying him the job was sustained. On May 23, 1881, Garfield appointed Bruce register of the treasury, which meant that Bruce's signature would appear on some of the nation's currency, an accomplishment that seemed to impress Bruce as much as his having served in the U.S. Senate. "Who would have thought of this spectacle a score of years ago!" he exclaimed. "This is an incident of interest worthy of a place upon the bright pages of the history of a public man's life."

Although Bruce was satisfied with the appointment, the editor T. Thomas Fortune criticized Garfield for not elevating Bruce to the cabinet. Bruce's great prestige, Fortune complained, "was hid away ... with his hands tied to his sides and his voice effectually stifled. The dignity of the Senatorial office and the faithful adherence, through thick and thin, of a million black voters, were stowed away in the oblivion of one of the bureaus of the Treasury Department."

Fortune's confidence in Bruce was not off the mark. The senator from Mississippi may well have been the most fully formed black politician of Reconstruction, a steady but quiet reformer who pushed hard on occasion, but who learned early how to maneuver and survive among influential whites. Known sometimes as "the Silent Senator," he usually

waited until near the end of a debate so as to have a better "lay of the land" before he went on the record. Perhaps because he spoke up so rarely, his words were that much more effective. No great intellectual like Frederick Douglass nor a firebrand like Ida B. Wells, he nonetheless made a popular tour of the lecture circuit after his Senate term ended (his seat was taken by James Z. George), speaking about the problems and promise of the black race in America and also about the need for equitable treatment for two of America's other minorities, the Indians and the Chinese. It was said that in 1886 he gave one hundred speeches for one hundred dollars apiece.