Captive Secrets (37 page)

Authors: Fern Michaels

He wanted this marriage even less than Gretchen didâif that was possible. He had never had much use for the Spanish. Furthermore, Gretchen's words now came back to taunt him. He too had heard of the piety of Spanish women, that they hung a rosary about their necks and prayed constantly to God to see them through their wifely “duty.” Would this one do that? Then perhaps it would be just as well if she were as homely as he suspected. She would doubtless smell of an unwashed body beneath her many layers of clothing and more than likely reek of garlic. Perhaps her father had merely wanted her out of his sight . . .

As his horse cantered along toward home, Regan turned his thoughts to the Javanese women he found so entrancing. Their comely looks, the clean and fresh scent of the sea hanging about them like an aura . . .

They

at least appreciated a man. They sought his favors and actually thanked him for “honoring” them.

They

at least appreciated a man. They sought his favors and actually thanked him for “honoring” them.

Ha. He knew that it was mainly because they felt it to be good luck to sleep with a white man; nevertheless, they were so uncomplicated . . so refreshing . . .

Like Tita . . .

He decided he would not bed the Spanish woman if he didn't like her looks. He would lock her away in the chapel and forget about her. Then it immediately dawned upon him that he did not have a chapel. He must see that one was built immediately!

What a far cry from Gretchen Señorita Córdez was sure to be. Brutal, fiery Gretchen, who had long wanted to marry him. As if he would marry her! She amused him, pleasured him, but he would never take her to wife. She was useful when his pent-up frustrations and hatreds began to get the better of him. Gretchen could take it, and could mete out some furies of her own! He laughed at himself as his horse quickened its pace, instinctively knowing it was nearing home.

He ought to pack off Señorita Córdez to Chaezar Alvarez, he thought. To that damned Spaniard!

Chaezar Alvarez held much the same position for the Spanish-Portuguese Crown in the Indies as Vincent van der Rhys had once held for the Dutch East India Company. Now Regan occupied that position. Based in Batavia, both men were responsible for the trade of their respective nations among the vast archipelagoâSumatra, Celebes, Borneo, Timor, Bali, New Guinea, and thousands of smaller islands, as well as Javaâsometimes called the Spice Islands. Theirs were positions of great responsibility: charting courses, warehousing cargoes, cataloging every yard of silk and pound of spice . . . in addition to keeping diplomatic channels open with the many inland chiefs and sultans.

Before Regan's father had come to take up his post on Java some twenty years before, the Dutch had not been faring well against the Spanish and Portuguese. The Netherlanders were too businesslike and aggressive to suit the gentle ways of the natives, whereas the Hispanic traders, educated by more than a century of world exploration, took the time to bring gifts and make friends with the tribes of the various islands. But the Dutch were determined to beat the Spanish and Portuguese at their own game. The efficient but personable Vincent van der Rhys, an established D.E.I. official in Amsterdam for some years, was sent out to manage the East Indian trade. A highly popular man and a born adapter, he succeeded marvelously well in his new post.

But Vincent van der Rhys's early days on Java had been lonely ones. Not only had his only child, Regan, been left behind with an aunt in Amsterdam in order to complete his education, but Irish-born Maureen, Vincent's ailing wife, had died en route to the islands. The middle-aged Dutchman was left only with his task of diplomat/trader. Nevertheless, a few years after his arrival in Java it became clear to all that the Dutch dominated the Spice Island trade at last.

Seventeen-year-old Regan van der Rhys sailed into what was later to be known as Batavia four years after his father, and set himself to the task of learning the business. At about that time a slick, sophisticated Spaniard only a few years older than Regan arrived in the harbor: Chaezar Alvarez, son of an impoverished Malágan don.

Regan had never liked the darkly handsome Chaezar, but the ratio of Europeans to native islanders in Batavia was so low that it behooved the small trading colonyâofficials of the two Crowns, sea captains, and merchants, and their wivesâto band together, if not for safety, at least for social commerce and friendship in this island paradise so far from their homelands. Such friendships as did develop, however, did not begin until after business hours, for the days were spent in an aggressive competition for trade.

Regan's distaste for Chaezar Alvarez was based less on his Dutch dislike of the Spaniard's affected grandeur and suave pretense than on the iniquitous role Alvarez had played in ruining Vincent van der Rhys . . .

In 1615, when Regan's son was four years old, he embarked with the child and his wife, Tita, on a voyage homeâto the Netherlands. It was to be a sentimental journey as well as one made for business reasons of his father's; it was to be a voyage of discovery and enlightenment for Tita and their child. But it was never to be completed. Before their ship, the

Tita,

captained by an old friend of Vincent van der Rhys, reached Capetown for reprovisioning, it was attacked by a shipful of Spanish-speaking pirates. Tita was murdered before Regan's own eyes, by the quick thrust of a Spanish broadsword, and the last time he saw his sonâbefore he himself was prostrated by the butt of a Hispanic musketâthe screaming boy's chubby hands were gripping the ship's wheel as a filthy bandanaed heathen lifted him to his battle-bloodied shoulders. Regan's memories of those scenes were indelible. As indelible as his enduring puzzlement that he, of all the crew, should have been singled out for survivalâprovided, indeed, with food and drink and set adrift in the ship's dinghy while the other passengers and the captain, dead or dying, were pitched overboard mercilessly. Someday, perhaps, he would learn the reason.

Tita,

captained by an old friend of Vincent van der Rhys, reached Capetown for reprovisioning, it was attacked by a shipful of Spanish-speaking pirates. Tita was murdered before Regan's own eyes, by the quick thrust of a Spanish broadsword, and the last time he saw his sonâbefore he himself was prostrated by the butt of a Hispanic musketâthe screaming boy's chubby hands were gripping the ship's wheel as a filthy bandanaed heathen lifted him to his battle-bloodied shoulders. Regan's memories of those scenes were indelible. As indelible as his enduring puzzlement that he, of all the crew, should have been singled out for survivalâprovided, indeed, with food and drink and set adrift in the ship's dinghy while the other passengers and the captain, dead or dying, were pitched overboard mercilessly. Someday, perhaps, he would learn the reason.

Two days later, or threeâfor his memory of the hours adrift was unclear now, eight long years afterâRegan had the good fortune to be spotted by a brigantine, again Spanish, but one of the merchant ships out of Java and bound for Cadiz. His good fortune lasted only until he was aboard-ships. Accused of being one of the crew of a recently demolished Dutch pirateer which had preyed on Portuguese and Spanish vessels approaching the African coast, he was manacled, impressed in the gallows of the ship, and taken to Spainâwhere, imprisoned without trial, he spent almost six years in a hellhole of a dungeon in Seville.

For nearly five years, the grief-stricken D.E.I. Chief Pensioner had given his son up for deadâbutchered along with Tita and his grandson. Until, one day, a merchant ship out of Rotterdam reached Batavia with the news that a Dutchman of Regan's description was an inmate at one of Philip III's infamous prisons in Seville or Cádizâhe was not certain which.

The news, however vague, aroused the elder van der Rhys. Further inquiries, made warily by one of his captains who, anchored at Cádiz for imaginary repairs and unnecessary reprovisioning, elucidated that a “VanderrÃ,” as the contact called him, was prisoner in Seville. And that, yes, the man was probably twenty-eight or ânine and blond-headed.

On receipt of this further information, Vincent van der Rhys made an unpleasant but necessary visit to the offices of the Spanish Crown in Batavia.

Yes, Chaezar Alvarez said, he would do all that he could; he was only too happy to know that his competitor's son still lived. But, he went on, inviting the aging Dutchman to a velvet-upholstered chair, there would be expenses . . . strings to pull . . . And, what was more, he confided to van der Rhys, Spanish trade had been hurt substantially over the past few years by the competence and persistence of the Dutch, and he, Chaezar, would welcome some of that trade. Or some of the profit from that trade. It would enhance his own position with his masters in Spain, might earn him a promotion, a return to the homeland . . .

Hundreds of thousands of gold sovereigns and a good portion of the Dutch trade later (Dutch ships were delayed by van der Rhys and reached their rendezvous with island chieftains later than the Spanish and Portuguese merchants), Chaezar Alvarez sent a letter to his godfather, Don Antonio Córdez, in Cádiz, in the hope that the old statesman and shipbuilder might sway Philip . . .

Now, four years later, Regan had repaired his father's losses, his personal fortune, and had reestablished the Dutch East India Company as leader in the Indiesâall the while concealing his father's shady dealings with the Spaniard, Alvarez. But the strain had been too much for the older man. His son regained, his honor and name untarnished, Vincent van der Rhys died.

“Alvarez!” Regan muttered, almost as an oath, as he reached his front gate. He knew Gretchen had amused herself with the slick Spaniard while he sat rotting in that Spanish jail! Alvarez . . . Regan's jaw contracted into tight knots just thinking of that Spanish swine.

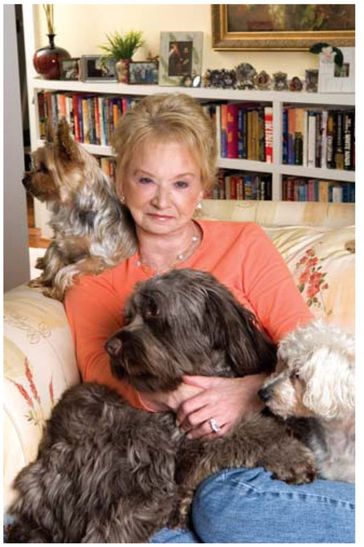

Photo by M21FOT0

©

2006

©

2006

FERN MICHAELS is the

USA Today

and

New York Times

bestselling author of the Sisterhood and

Godmother series,

The Blossom Sisters, Tuesday's Child,

Southern Comfort, Betrayal, Return to Sender

and dozens of other novels and novellas.

USA Today

and

New York Times

bestselling author of the Sisterhood and

Godmother series,

The Blossom Sisters, Tuesday's Child,

Southern Comfort, Betrayal, Return to Sender

and dozens of other novels and novellas.

There are over seventy million copies of her books

in print. Fern Michaels has built and funded several large

day-care centers in her hometown, and is a passionate

animal lover who has outfitted police dogs across the

country with special bulletproof vests. She shares her

home in South Carolina with her four dogs

and a resident ghost named Mary Margaret.

in print. Fern Michaels has built and funded several large

day-care centers in her hometown, and is a passionate

animal lover who has outfitted police dogs across the

country with special bulletproof vests. She shares her

home in South Carolina with her four dogs

and a resident ghost named Mary Margaret.

Â

Visit her website at fernmichaels.com.

Fading into the background isn't the Sisterhood way. Even after all the adventures they've shared, the courageous, close-knit heroines of Fern Michaels'

New York Times

bestselling series are always ready to embrace another challenge . . .

New York Times

bestselling series are always ready to embrace another challenge . . .

Â

All good things must come to an end. But Myra Rutledge isn't ready to put the Sisterhoodâthe stalwart band of friends who've become legendary for meting out their own brand of justiceâbehind her just yet. Though she loves her beautiful home and her husband, Charles, Myra can't deny that she's restless. And as it turns out, she's not the only one longing to dust off her gold shield and get back in action.

Â

When Maggie Spritzer, former editor-in-chief of the Post and an honorary member of the Sisterhood, arrives with a new mission in mind, Myra welcomes her in. Maggie's newshound instincts haven't dulled since she left the

Post,

and she suspects that two Maryland judgesâidentical twins Eunice and Celeste Cipraniâare running a moneymaking racket that sends young offenders to brutal boot camps, often on trumped-up charges.

Post,

and she suspects that two Maryland judgesâidentical twins Eunice and Celeste Cipraniâare running a moneymaking racket that sends young offenders to brutal boot camps, often on trumped-up charges.

Â

Soon the Vigilantes are gathering in their war room once more, catching up on the momentous events in each other's lives even as they plan their campaign. The Ciprani twins are powerful and ruthless, and taking them down won't be easy. But with the aid of formidable alliesâincluding former President Martine ConnorâMyra, Annie, Maggie and the gang concoct a scheme that will bring justice to the innocentâand eave the guilty blindsided . . .

From the beloved #1 bestselling sensation Fern Michaels, a haunting portrait of love and warâand the passionate woman swept into an epic journey of desire, heartbreak, and destiny.

Â

Â

Casey Adams, a dedicated nurse, loses her heart overseas

to idealistic officer Mac Carlin, heir to an immense

fortune. Then tragedy strikes. Believing that Casey has

died in an explosion, Mac returns to San Francisco

grief-stricken, to a life he never wanted. But Casey is still

alive, keeping Mac in the dark after learning that he kept

from her a shattering secret. Once home, Casey finds

healing in the hands and heart of a brilliant plastic surgeon

and forges ahead under a new name and with a new career.

But fate charts a collision course for her and Mac, now

a U.S. senator who doesn't recognize the compelling

TV producer getting under his skin. For Casey, this full-

circle journey cannot be denied, no matter what. For only

by reclaiming the woman she was and the life she lost

can she embrace the magic of unexpected love.

to idealistic officer Mac Carlin, heir to an immense

fortune. Then tragedy strikes. Believing that Casey has

died in an explosion, Mac returns to San Francisco

grief-stricken, to a life he never wanted. But Casey is still

alive, keeping Mac in the dark after learning that he kept

from her a shattering secret. Once home, Casey finds

healing in the hands and heart of a brilliant plastic surgeon

and forges ahead under a new name and with a new career.

But fate charts a collision course for her and Mac, now

a U.S. senator who doesn't recognize the compelling

TV producer getting under his skin. For Casey, this full-

circle journey cannot be denied, no matter what. For only

by reclaiming the woman she was and the life she lost

can she embrace the magic of unexpected love.

An unforgettable novel from the national bestselling sensation Fern Michaels, about a young woman's journey into the heart of the unknown . . .

Â

Â

Callie James learned to survive in the squalid back alleys

of Dublin. Tough, spirited, and possessed of a singular

beauty, she was sent to New York to find her fortune.

But everywhere she turned there were men who saw only

what they wanted to see in her. Byrch Kenyon offered

friendship and encouragement, but he also saw the

desirable woman she would one day become.

of Dublin. Tough, spirited, and possessed of a singular

beauty, she was sent to New York to find her fortune.

But everywhere she turned there were men who saw only

what they wanted to see in her. Byrch Kenyon offered

friendship and encouragement, but he also saw the

desirable woman she would one day become.

Rossiter Powers, the rich son of a respected family, saw something else in Callieâand nearly destroyed her. Hugh MacDuff, rich only in love and compassion, did his best to save her. But Callieâstrong, smart and determined to succeedâinsisted on taking charge of her own destiny.

Other books

Seduced At Sunset by Julianne MacLean

Silk Is For Seduction by Loretta Chase

Sophomore Switch by Abby McDonald

Never Never by Kiernan-Lewis, Susan

Genetic Attraction by Tara Lain

Lexington and 42nd (The Off Field Series #1) by Kim Carmody

The Dream Sharing Sourcebook: A Practical Guide to Enhancing Your Personal Relationships by Phyllis R. Koch-Sheras

Kathlyn Trent, Marcus Burton 01 - Valley of the Shadow by Kathryn Le Veque

13 Little Blue Envelopes by Maureen Johnson

Empire of Bones by Liz Williams