Read Catastrophe: An Investigation Into the Origins of the Modern World Online

Authors: David Keys

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Eurasian History, #Asian History, #Geology, #Geopolitics, #European History, #Science, #World History, #Retail, #Amazon.com, #History

Catastrophe: An Investigation Into the Origins of the Modern World (24 page)

And in Shaanxi province, “the land within the Passes,”

The Annals of

the Western Wei

in the

Bei shi

state that there was “a great famine,” and that “the people practiced cannibalism and 70 to 80 percent of the population died.”

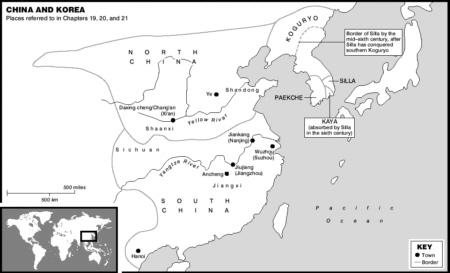

“In the following year [in March], because there had been hail and drought in nine provinces, there was a great famine and as the people fled [in search of food] I begged [the emperor] that the [state] granaries should be open to give relief,” wrote a senior government official, as the climatic dislocation continued. In the summer of 538 in what is now the province of Shandong there was a massive flood. The waters rose so high that “the toads and frogs were croaking from the trees.”

2

The climatic chaos and its resultant agricultural failures appear to have had two immediate political consequences. First, the emperor of southern China tried to invoke the powers of heaven to improve the situation.³ He decided that he personally would carry out the state’s major annual agricultural religious ritual, the ceremonial plowing of the imperial wheat field.

In this ritual, in March the emperor personally plowed the first furrow in the field. The three highest governmental officials then did the next nine furrows (three each), followed by other top officials, who did five each. Selected commoners did the rest. The ritual plowing was preceded by a grain offering to a Chinese-style agriculture god, the Divine Husbandman, who they believed had long ago given the knowledge of agriculture to the Chinese people.

The imperial plowing ritual had fallen into disuse for most of the fifth century and was performed only infrequently in the first third of the sixth century. Then in 535 climatic disaster and crop failure seem to have forced the southern authorities to make it an annual ritual, and it was held each year from then until 541, excepting 539. They had to be seen by the population to be doing something to remedy a situation in which tens of thousands of people—perhaps even hundreds of thousands—were dying.

The second political consequence of the famine was far more serious. The crop failures and the result of social dislocation and poverty undermined the economy of the southern Chinese state. The tax system virtually collapsed, presumably because there was no surplus wealth to collect. The 538 tax amnesty—introduced in twelve provinces because of famine deaths—was repeated in 541, but this time throughout southern China and for a period of five years. After that it was extended three more times, until 551.

The initial reason for the collapse of the tax system was certainly the poverty caused by the famine, but other related causes lay behind the constant renewal of the amnesty. As poverty persisted and the lack of tax revenue destroyed the government’s ability to rule effectively, popular revolts began to break out.

4

Three are known—one ethnic, one probably partly religious, and one political—but there were probably others of which no record survives.

The ethnic revolt almost certainly owed its genesis to the weakened state of central government at this juncture. Its epicenter was the Hanoi area of Vietnam, which was then part of the southern Chinese state. Under the leadership of a commoner called Li Fen (probably a Sinicized Vietnamese), the rebels defeated the local Chinese governor in 541 and then two years later humbled an army led by a member of the emperor’s family, the Prince of Linyi. Soon the rebel leader, buoyed with confidence, started calling himself emperor. With central government massively weakened in financial terms, it took another two years to suppress the revolt. But eventually—in 546—Li Fen was captured and thrown into a cave, where presumably he perished.

The second revolt was briefer but, in a way, perhaps more serious than the Vietnamese uprising. It broke out in 542, engulfed an area only three hundred miles southwest of the capital, near the city of Ancheng, and owed its origins to the famine in two ways. Like the Vietnamese insurrection, the Ancheng rebels almost certainly took advantage of the tax-starved central government’s weakness. Perhaps more significant, the rebels probably saw the famine and the ensuing poverty in millenarian religious terms.

In conventional Buddhist belief, the next Buddha—the Maitreya—will return to save the world when the last Buddha’s message of ethical enlightenment has been forgotten and the world is again totally steeped in evil. This “second coming” is not thought of as being imminent. It is something that will be necessary only thousands of years hence. But in nonconventional “heretical” Buddhism—the so-called Left Way—the Maitreya was expected rather sooner. It is likely that the Ancheng rebels included just such messianic radicals who regarded the increased levels of poverty and suffering as evidence that the world had entered a period of darkness and decay and that the coming of their Messiah was imminent. They may well have seen their revolt as preparing the way for their savior.

The entry in the

Nan shi

for early 542 is quite terse—it suggests the probable heretical affiliations of the rebels in its note that ‘’the commoner Liu Jinggong from Ancheng commandery, embraced the Left Way and rebelled.” His followers, who numbered tens of thousands, took over some five thousand square miles of what is now northern Jiangxi province. In the end, the emperor’s son, Prince Yi (of whom more later), sent an army that successfully defeated the rebels and captured their leader, Liu Jinggong, who was taken to the capital and beheaded in the city’s central marketplace.

By 546 the country was in such an appalling financial state that the currency began to lose its value. In 547 it was said that more rebellion was brewing. As in other parts of the world, the climatic events of the mid-530s ushered in a period of climatic instability, and in 544, 548, and 549 China was hit by three more droughts.

In the northern Chinese

Bei shi,

a major drought is cited for 548, while

The History of the Southern Dynasties

records extremely serious droughts and subsequent famines in 549 and 550, in which the population was reduced to cannibalism in some areas. The accounts say that in the famine of 549 “people ate each other” in the great city of Jiujiang (now Jiangzhou) on the south bank of the Yangtze, and in 550 “from spring until summer there was a great drought, people ate one another and in the capital [modern Nanjing] it was especially serious.”

As these new droughts raged—and with the government weak and starved of taxes—a third revolt broke out with substantial peasant backing. In 547 a northern Chinese general, Hou Jing, defected to the south, and as a result, the huge tract of northern territory he controlled became at least nominally part of the southern state.

The northern government understandably took immediate action to recover its lost land, and within a year Hou Jing had been defeated, his territory fell again under northern control, and the defeated general fled south. The southern government then made peace with the north, and Hou feared he would be handed over to his former northern colleagues as part of the peace treaty. Faced with such a fate, and knowing the weaknesses of the southern Chinese state, the general rebelled in August 548. His revolt, though caused by the political pressures of the day, would not have stood any chance of success if it had not been for the massively increased levels of poverty and government weakness that were results of the drought and famines.

He openly courted the poverty-stricken rural peasantry and the urban poor, and it is very likely that at least some of his peasant supporters harbored Left Way messianic hopes, as the peasants in Ancheng had six years earlier.

He marched on the southern capital, Jiankang (now Nanjing), and camped outside its massive walls. After a siege of just four months, the city surrendered. The general—who was of Turkic, not Chinese, origin—despised the Chinese aristocracy. Many of the capital’s poorer citizens had escaped from the city and were welcomed by the rebels. Indeed, when the rebels entered Jiankang, they found senior aristocrats starving to death in their palaces and deserted by their retainers, yet still clad in their traditional finery. The emperor himself, now in his eighties, was captured by the rebels, and is said to have been left to starve to death in his imperial palace.

Hou Jing was finally defeated in 552, but the southern state was exhausted and shattered. The general’s revolt had become in many ways a popular revolution against poverty, famine, and traditional aristocratic rule. One of China’s greatest epic poems—

The Lament for the South,

written by a southern civil servant—described in metaphoric terms how the circumstances of the mid-sixth century made disaster inevitable:

We were sailing over leaking-in water,

In a glued-together boat,

Driving runaway horses with rotten reins,

Trying with a worn-out sieve to make the salt lake less brackish.

5

The 520-line epic also described how Hou Jing incited popular revolt and attacked the imperial capital:

He then stirred up the unruly,

And invaded the royal domain,

Halberds hacked the twin towers [of the palace],

Arrows struck the thousand gates.

The defeat of the imperial forces at the siege was a disastrous and bitter experience for the aristocracy, including the author of

The Lament

:

Drums toppled, standards broken,

Riderless horses lost from the troop,

Confused tracks from fleeing chariots,

Brave warriors kept inside the walls,

Wise advisers held their tongues,

As if the [fierce] elephants had fled to the forest,

Or the [ever-resourceful] snake was to flee to its hole.

But catastrophe did not cease at the fall of Jiankang. In a sense, the revolt simply exacerbated it. The Hou Jing rebellion, successful because of the increasing weakness of the state, totally destabilized south China. The rebel victory had created a sort of political vacuum. Because Hou Jing was an outsider, a populist rebel who had no connection to the ruling dynasty and was not even ethnically Chinese, his brief regime was not regarded as having any legitimacy at all. His puppet emperor—a virtual prisoner whom he murdered in the end—must have been seen as no more than a captive marionette.

6

From the day the capital fell to the rebels, a bloody, often multisided civil war broke out within the remnants of the old ruling dynasty. Over the next eight years, south China was to have no less than ten emperors—puppets, children, and assorted megalomaniacs. Usually there were two, sometimes three, claiming to be emperor at any one time, and most ended up as murderers, murder victims, or both. The warlord with the most blood on his hands was one of the previous emperor’s children, Xiao Yi, who killed his nephew and his own brother and drove a second brother to his death. The murderer was then slaughtered by another nephew.

South China broke into three major power centers—Jiankang in the east, Sichuan in the west, and, in the middle, the central Yangtze. While dynastic brother fought dynastic brother in the south, the north Chinese powers of Northern Qi and Western Wei busied themselves grabbing as much southern territory as they could digest.