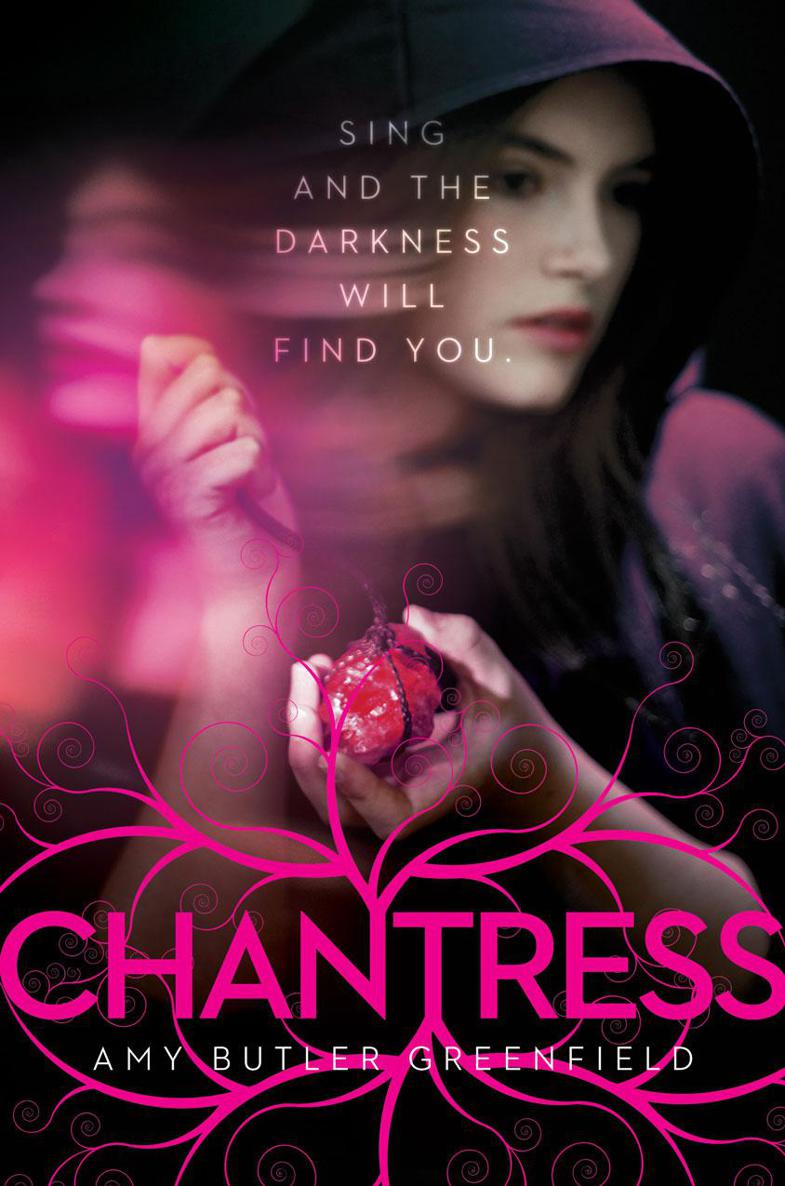

Chantress

Authors: Amy Butler Greenfield

Thank you for downloading this eBook.

Find out about free book giveaways, exclusive content, and amazing sweepstakes! Plus get updates on your favorite books, authors, and more when you join the Simon & Schuster Teen mailing list.

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com/teen

Chapter Six:

A Small but Convincing Display

Chapter Fourteen:

The Apothecary’s Shop

Chapter Fifteen:

The Invisible College

Chapter Sixteen:

A Meeting of Minds

Chapter Seventeen:

A Step Too Far

Chapter Twenty-One:

Plans and Questions

Chapter Twenty-Two:

Under the Ground

Chapter Twenty-Five:

Explorations

Chapter Twenty-Seven:

An Old Song and a New One

Chapter Twenty-Eight:

Playing with Fire

Chapter Twenty-Nine:

Revelations

Chapter Thirty-One:

The Delegation

Chapter Thirty-Two:

A Question of Power

Chapter Thirty-Seven:

The Truth

Chapter Thirty-Eight:

At the Heart of Fear

Chapter Thirty-Nine:

The Reckoning

FOR T., WHO SINGS HER OWN SONGS

Chantress

[a. OF.

chanteresse

, fem. of

chantere

,

-eor

, singer: see CHANTER and -ESS.]

1.

female magician, sorceress, enchantress.

2.

A female chanter or singer; a singing woman; a songstress.

—Oxford English Dictionary

† † †

A dangerous disease requires a desperate remedy.

—attributed to Guy Fawkes (1570–1606)

THE SINGING

I was digging in the garden when I heard it: a strange, wild singing on the wind.

I sat back on my heels, a carrot dropping from my mud-splattered hands.

No one sang here. Not on this island.

Perhaps I’d misheard—

No, there it was again: a lilting line, distant but clear. It lasted hardly longer than a heartbeat, but it left me certain of one thing: It was more than a gull’s cry I’d heard. It was a song.

But who was singing it?

I glanced over my shoulder at Norrie, hunched over a cabbage bed, a gray frizzle poking out from under her linen cap. As far as I knew, she was the only other inhabitant of this lonely Atlantic island, but it couldn’t have been Norrie I had heard. For if there was one rule that my guardian set above all others, it was this one: There must be no singing. Ever.

Sing and the darkness will find you.

We were still dripping from the shipwreck when Norrie first told me this. She had repeated it often since then, but there was no need. The terror in her eyes that first time had silenced me immediately—that and my own grief, so deep I was drowning in it. The sea had taken my mother and had almost taken me. That was enough darkness to last me a lifetime; I had no desire to court more.

Not that I could recall very much about the shipwreck itself. Even the ship that had carried us off from England seven years ago had left no impression on me. Was it stout or shaky, that vessel? Had it foundered on rocks? Had storms broken its masts? I did not know. We had boarded that ship in 1660, when I had been eight years of age. Surely eight was old enough to remember? Yet my only recollections of that night came in broken fragments, slivers that were more sensation than sense. The sopping scratchiness of wet wool against my cheeks. The bitter sea wind snarling my hair into salty whips. The chill of the dark water as I slipped through it.

“Hush, child,” Norrie would say whenever I dared mention any of this. “It was a long time ago, and a terrible night, and you were very young. The least said about it, the better.”

“But my mother—”

“She’s lost to us, lamb, lost to the wind and the waves.” Norrie’s face would always pucker in sadness as she said this, before her voice grew brisk. “It’s just the two of us now, and we must make the best of it.”

When Norrie took that tone, there was no refusing her. So

make the best of it we did, and if life on our island was not easy, it was far from desolate.

But we never sang. We never even whistled or hummed. We had no music of any kind. And if anyone had asked me, I would have said I did not miss it at all . . . .

Until now.

It was as if the singing had pierced a hole in me, a hole only it could fill. I sat silent, listening hard. Withered stalks rustled in the warm October sunlight. Gulls shrilled as they swooped toward the bluffs. And then, on the wind, I heard it again, the barest edge of a tune, almost as if the sea itself were singing—

“Lucy!”

I jumped.

From two rows away, Norrie waved her wooden trowel in her gnarled hand. “What’s wrong with you, child? I’ve harvested a whole basket of cabbages in the time it’s taken you to root out three carrots.”

It didn’t matter that I stood half a head taller than Norrie did, or that I thought of myself as nearly grown—she still called me

child

. But I was too used to it to bristle. Instead, I looked down at my meager takings. If Norrie had heard the music, surely she would have mentioned it. Since she hadn’t, I wasn’t going to. I didn’t care to have her scolding me, yet again, for having too much imagination and not enough sense. Was the singing real? I was almost willing to swear it was . . . but not quite. Not to Norrie.

“Well, Lucy, what is it?” Norrie knocked the dirt from her trowel. “Are you ill?”

“No.” If anyone looked ill, it was Norrie. Every year the harvest was more of a struggle for her. It scared me to see her cheeks so mottled, her stout shoulders drooping. I knew she wouldn’t appreciate my saying so, though.

“You’ve been working since sunrise,” I said instead. “Don’t you think you’ve earned a rest?”

“Rest?” Beneath her rumpled cap, Norrie looked scandalized. “On Allhallows’ Eve? Whatever can you be thinking?”

“I only meant—”

“Back to work now, and no more dawdling, please,” Norrie said, her face anxious. “We need those carrots, every single one, if we’re not to go hungry this winter.”

“I’ll get them all,” I promised, hoping to calm her.

Norrie’s brow relaxed a little, but her back was still tense as she bent over her cabbages again.

I wrapped my hands around a frill of carrot and sighed. Allhallows’ Eve, the thirty-first of October—every year I dreaded this day. For if Norrie was strict as a general rule, on Allhallows’ Eve she was at her absolute worst. From dawn to dusk, she worked us half to death, dragging in the last of the harvest and safeguarding the house against the coming night.

“After sunset,” she would say. “That’s when the true danger comes. The spirits walk, and mischief is in the air. We have to protect ourselves.”

Maybe so. But to me the preparations seemed an endless burden, especially as I had never seen any sign of the mischief Norrie talked about.

Unless the singing . . . ?

But no. If singing was what Norrie had meant by mischief, I reasoned, surely she would’ve said so. And anyway, the sun was still golden bright. Rather low in the sky, but a good way from night.

Yet I worked a little harder, if only because I owed it to Norrie. For seven years, she had raised me singlehandedly—not without a fair amount of scolding and sighing, to be sure, but always with real affection. Now that she was growing older and her strength was ebbing, I knew it was up to me to return the favor, and look after her. If she wanted the harvest brought in before nightfall, then we would bring it in.

So I piled the carrots high, and when Norrie next turned to see me, she smiled in satisfaction. But while I worked, my thoughts were my own. With part of my mind, I listened out for the singing. The rest of me wished desperately for a life bigger than carrots and harvests and Norrie’s superstitions.

I knew, none better, that the island had pleasures to offer—the silky white sand of its beaches; hidden coves speckled with shells; sun-drenched mornings at the water’s edge. But they could not compensate for the isolation we endured, or for the relentless drudgery of our daily existence.

Our life in England had not been like this. I remembered a cottage by the sea, bright with my mother’s wools and weaving, where guests told stories by the fire. Before that, I had only a scattered patchwork of memories, but they were colorful and varied: a game of hide-and-seek in a castle’s great hall, a tiny garret room

perched by the River Thames, the green smell of bracken by a forest lodge.

“We moved often in those early years,” was Norrie’s only comment about that time. “Not that I’m blaming your mother, mind you. She had to look out for herself, what with your father dying before you were even born, leaving her all alone. But the Good Lord didn’t mean for a body always to be traveling hither and yon. Best to set yourself down in one place and stick to it, that’s what I say.”

She was as good as her word. She had rooted herself so deeply on the island that I half feared she would refuse rescue if it were offered.

Me, I would swim out to meet the ship. I longed for new sights and adventures, for a life not bounded by the island’s shore. Above all, I longed for freedom—especially as Norrie grew ever more dogmatic about everything from what we had for Sunday breakfast to how many peat bricks we should burn in the fireplace.

With a sigh, I gathered up my carrots. Norrie had countless rules about those, too—not only about how to harvest and sort them but how to store and when to eat them.

A ship

, I found myself praying.

Oh, please send a ship.

But what was the use of praying? I had been waiting and watching and hoping for seven long years, and no ship had ever come.

Seven years, and no rescue in sight. Seven long years on this island. And how many more to follow?

Wincing, I rose and tossed my carrots into the waiting baskets. They thumped as they hit the pile—and that’s when I heard the singing again.

The notes cascaded around me, stronger this time and more urgent. For a reckless moment, I wanted nothing so much as to give voice to the music myself, and sing it back to the wind. But then, like a muzzle, came Norrie’s warning, the endless refrain I’d heard since childhood: