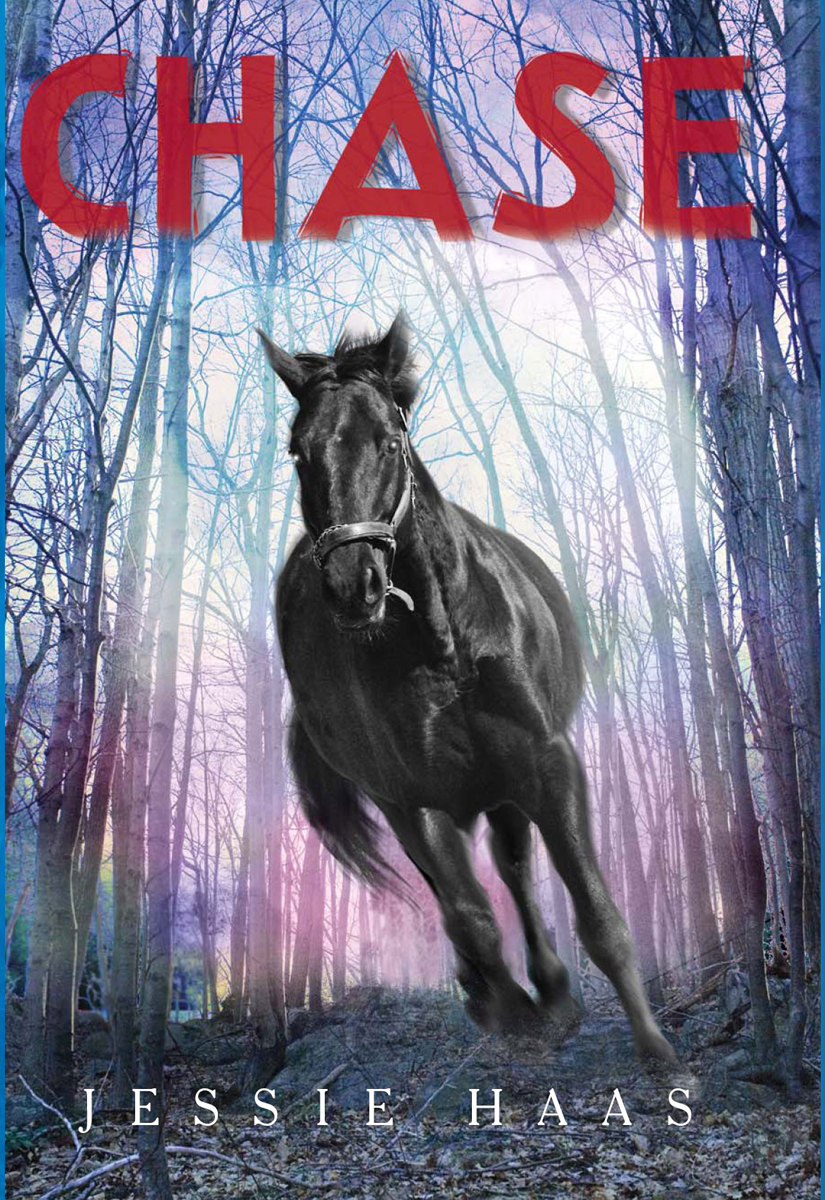

Chase

Authors: Jessie Haas

Chase

For the Monday Night Group: Pam Becker, Erica Breen,

Jay Callahan, Michael J. Daley, John Steven Gurney,

Erin Heidorn, Andra Horton, J. D. McNeil,

Rose-Marie Provencher, Jean Rice Shaw, Jeanne Walsh,

and the late Seth Wheeler

and for Rebecca Davis

1.

Engelbreit

2.

Widow's Row

3.

The Dog Hole

4.

Jimmy

5.

Drove

6.

Dennis

7.

Dark Horse

8.

Train to Meet

9.

Hold or Fold

10.

Lining Out

11.

Water

12.

Out

13.

Pursuit

14.

Alone

15.

Follower

16.

Phin Again

17.

The Last Egg

18.

Beaver Dam

19.

Thin Dark Line

20.

Beechnuts

21.

A Man Complete

22.

Dead-and-Alive

23.

Match Light

24.

Bloodhound

25.

The Transparent Eye

26.

On the Way

27.

Blood Money

E

NGELBREIT

P

hin surfaced from the book with a start and sat listening; for what, he wasn't sure.

It was hours later, the lamp pale and unneeded, the sky blue, with a glowing red-orange streak at the horizon. Engelbreit was sleeping late this morning. Dawn usually found him up and breakfasting, then off to the mine to meet the incoming shift. In these troubled times it was best to be on hand early, to smell out whatever mischief had brewed overnight.

But Engelbreit was only just stirring in his blankets. That must be the sound that had startled Phin. Then why was he still listening? Why was he thinking of his mother?

He glanced down at the great poem he'd been so deep in moments ago. They'd never shared

Leaves of Grass.

It was two weeks after her death that he'd discovered Engelbreit and his books.

There were twenty-two of them on the shelf next to the table. Four had to do with coal and engineering, but there were novels, history, and poetry, too. Engelbreit wouldn't loan them. He'd caught Phin reading a novel left on the bench outside his door. “Come anytime,” he'd said. “If I'm asleep, don't wake me. Just light the lamp and read.”

For ten months now Phin had come almost every night. It felt more like home than the empty room behind Murray's Tavern. He missed her less here, and more.

Isn't this beautiful?

he kept wanting to ask her; or

What do you think?

And he'd look up from the page and remember.

But this wasn't one of those times. He didn't feel sorrowful, justâuneasy.

He leaned to blow out the lamp as Engelbreit rose, shoved his feet into his boots, and opened the front door wide. The sun was just coming up.

Engelbreit went out, dipped water from the barrel, and washed his face and hands. He came back in, leaving the door open. It was early autumn. The breeze brought a spicy smell from beyond the coalfields.

“Do you ever sleep, boy?” He rubbed his palms over his face; broad, bearded, maned like a lion. His calm blue eyes looked curiously at Phin, who shrugged. Sleep was hard to come by at a saloon. Sometimes he slept in the early morning, when things got quiet, or he'd slip away to the stable and bed down in the hay. Engelbreit didn't know that, and he didn't know much about Engelbreit. What they spoke of when they got the chance was books, and they didn't get the chance often.

Engelbreit drove his men like a demon, so the talk ran at Murray's. Phin had seen him come home, this demon, as soaked with sweat as any black-faced miner; throw himself on the bed and lie there wide-eyed, too exhausted to sleep. He'd seen him at his figures, shaking his head. The numbers didn't come out right. Working like a demon wasn't enough, for him or anyone else these days.

Engelbreit bent to kindle a fire in the stove. The sun struck a golden spear through the doorway. “Have some breakfast, since you're here?”

Just then a shadow crossed the sunbeam on the floor, then two more shadows. Shoulders. Hats. Like dark dolls the shapes lengthened over the clean-swept boards. Phin looked around.

Ned Plume came first, walking straight to the door with

a revolver in his hand. He carried it down by his side, casual as a man with a dinner pail. He was tall and straight and his shoulders swung easily. The two behind were nervous and had been drinking.

There was time for one word. “Sleepers,” Phin said, and Engelbreit turned from his breakfast.

Turned slowly. It was already too late. His eyes were fearless, and Plume raised the gun and fired. Red blossomed on Engelbreit's shirt and he fell back. When his head struck the iron stove, the look in his eyes didn't change. He was already gone.

Â

Phin had seen dead men. In coal country in 1875, you did.

But Engelbreit. The sun through the open doorway, bright rose of red on his shirt. Engelbreit's calm eyesâ

The next shot would slam into Phin. He refused to turn and see it. Engelbreit's face would be his last sight on earthâ

Footsteps, a rustle of clothing. Hands grabbed his upper arms, hard and hot as iron from the forge. He was jerked around to face Ned Plume.

The morning light gilded Plume's face. He looked handsome and noble, like a dime-novel hero, as he raised his gun again.

Phin swooped out of his body to a high corner of the ceiling. He saw the gun leveled at him, a shabby boy with a mended tear in the top of his cap. The boy looked calm, as detached as Engelbreit. Plume squared his jaw, squared it again, and his knuckle whitened on the trigger.

Abruptly he dropped his gun hand to his side. “This one I can't do.”

Phin fell back into his body, a shrinking prison of fear. “He knows something,” said the man holding him. “âSleepers,' he said.”

But everyone knew the Sleepers. You pretended not to, but you did. And working at Murray'sâan Irish tavern, in an Irish mine townâyou'd have to be blind and deaf not to. The SleepersâMolly Maguires, Ancient Order of Hibernians, to give them their other namesâwere the Irish defense force. Or they were a band of thugs; opinion was divided, even among the Irish.

Phin knew about the secret passwords and handshakes; about the coffin notices, threats with black coffins drawn on them to scare off oppressive bosses. He knew about the body masters who headed each local group. He knew about the gunmen. But everyone was aware of those things. He'd known everything, and nothing; certainly nothing worth dying for, until now.

“You do it,” Plume said. The hands holding Phin jerked. Plume laughed. “Not so easy, is it? But here's a planâ”

“Who is the kid?” a voice outside asked.

“Mary Chase's boy. Works for Murray,” Plume said. “English.”

“Mary was Irish, I thought.”

“The father was English.”

“No matter,” Plume said. “Didn't we walk in here, boysâto discuss our legitimate grievances!âand find Engelbreit dead and this lad tossing the place!” As he spoke, Plume moved casually through the little room, yanking open a drawer and scooping out the clothing, kicking over a chair. “No one more shocked than ourselves, mind”âhe cleared the books from the shelf in one long sweepâ“and we restrained ourselves from stringing him up, and decided we'd turn him over to the constable.”

A Sleeper. The constable was a Sleeper.

“Engelbreit was liked upstairs,” said the voice outside the door. “Lot of vigilante talk. Maybe the lad won't live till his trial.”

“Maybe not.” Plume turned toward the door. “Bring him. They've ignored the shot as long as they can, on the Street. They're coming.”

The iron hands loosened, shifting to grip the back of Phin's jacket.

Phin didn't think, just twisted out of the loose-fitting garment and dived across the table. He kicked the book and the lamp fell and he went through the window, finding his feet while glass still clinked to the ground. Around the corner, tearing the window sash off his neck. A shot. Anotherâ

His legs pumped and his loose shirt flapped against his ribs. Wind droned in his ears, a hollow sound like a set of pipes. Faster than he'd ever run, but it felt slow. He saw everything clearly, as if with his whole body, not just his eyes. A pigpen built of fresh slabs; the pitch dripped like honey, glistening in the sunlight. A woman threw a basin of water out her back door in a gleaming pewter arc. Did he touch the ground, even? He didn't feel his feet, didn't feel anything or fully snap into his body again, until he reached the yard of Murray's Tavern.

Two habitual drunks snored in their habitual corners. Duff Murray stood in the doorway, scratching his bristled jowl and then scratching under his shirt. His eyes were small and red-rimmed, and blinked resentfully at the sun.

Phin half fell to a stop. He'd come here because it was

home, but it was the wrong place. He turned his head, ready to run. Murray's big hand shot out, swift as a frog snapping a fly, and caught him by the shirt.

“Wood,” he said. “Wash.” As well as spirits and games of chance, Murray's offered rooms and breakfasts and clothes laundered, a dozen useful ways for a boy to earn his keep.

Phin tried to speak. His dry lips couldn't form the words. He licked them with a dry tongue.

“They shot him!”

“Engelbreit.” Murray's red eyes were unmoving. “How does that concern me?”

Fear congealed like cold grease around Phin's bones. He hadn't said who was shot, but Murray knew.

“Theyâ” he said.

Murray said nothing.

“They'llâswear it off on me. I'll hang.”

Murray's face didn't change. “You were where you didn't belong, boy. Else how would you know about it.”

The heap of clothing in the corner near the door stirred. That was Jim Kane, who by afternoon would be up and sauntering around, bright-eyed, and who by evening could dance a jig and sing a tune with the best of them, until he collapsed again about two in the morning. Usually he slept till noon, but their voices were disturbing him.

When he awoke, he'd see Phinâand Jim Kane would sell anything to anyone for the price of a drink.

“Please,” Phin said.

The ugly face didn't soften, but the grip on Phin's shirt slowly did. “One favor,” Murray said finally. “For your mother's memory. I haven't seen you.” He spun Phin around as lightly as he'd spin a glass onto the bar, and twitched him free.

W

IDOW'S

R

OW

H

e'd run the breath out of his body, the bones out of his legs. He stumbled around the corner, blundered into a fence, leaned there, heaving for breath, trying to hear above the blood pounding in his ears.

The ground shook; a charge going off underground. The shift had started workâso they didn't know yet. That meant Mahoney didn't know, either. The Sleeper constable always managed to be below when Sleeper mischief was afoot.

Phin pushed off from the fence, driving himself on, past plank houses, plank fences, bare dirt yards and scrubby trees, a back garden, a tethered goatâ

“Phin?”

A woman's voice. He stopped, legs braced wide to hold himself up, and turned blindly.

“Phin Chase, what are you up to?” Beautiful red-haired Margaret Wimsy stood at the doorway of her cabin, fastening up a morning glory vine. “Come here!” she said.

He heard hoofbeats now, distant but coming this way. He wanted to run,

must

run. Yet he walked toward Margaret through the syrupy, resistant air. His head felt an immense distance from his feet.

“Take this to Murray's for me, will you?” She handed him a package, wrapped in newspaper and tied with a piece of tired ribbon. “Tell Murray put it in a safe place.” Turning back to her flowers, she spoke over her shoulder. “A fine, careless man, Ned Plume, but he'd skin a flea for its hide and tallow. Must have a lot on his mind this morning, leaving his wallet here!”

His wallet.

Plume's

wallet.

Fear-sweat dampened Phin's face. He ducked his head to hide it. Did she know what Plume had on his mind?

Could

she know, and handle her flowers so carelessly?

Her voice came as if from a distance. “Tell Ned I said you're to have a penny for your trouble. Put that away now. Don't carry it out in the open.”

No. Not out in the open. Phin slid the package into his pocket.

“Cool morning to go without a jacket, Phinny!”

He risked a glance at her face. Not motherly, Margaret, but she'd been his mother's friend, and she looked out for him, though it didn't come naturally. A moment more and she'd notice the state he was in. He turned numbly, and heard her close her door.

Was the wallet full of money? Did she care?

She might not. Like a queen out of the old tales, Margaret Wimsy did as she liked. Drank at Murray's; decent women didn't. Chose her own man, and chose again if another pleased her better. Last year when Ned Plume came to Bittsville, he became Margaret's at once. Phin remembered the clash of their eyes across the smoky room, the challenge flung down and accepted. They were like a pair of eaglesânothing soft about their love. “There must be more to him than meets the eye,” Phin's mother had said. “She's no fool, Margaretâbut I still think she could do better.” Maybe, but not here in coal country. Ned Plume was top Sleeper gunman. His belongings were safe anywhere in Bittsville; no one would filch so much as a cigarette paper.

Phin had his whole wallet.

The thought kicked him forward in a wavering run, angling among the fences and back sheds, ever farther from the Street. The ground boomed and jumped beneath him, the breaker growled, and under those sounds came the hoofbeats, closer, slowing as if they were right among the houses. Phin swerved uphill, into the narrow lane of Widow's Row, forcing himself to walk.

Here the morning was loud with goats and babies, women talking, children shouting. The houses were tiny and leaned toward each other in a gossipy way across rickety fences. Miners' widows and orphans lived here. During the war, when he was small, Phin and his mother had too.

His father was still alive then, but he'd been marched away with six other Bittsville miners, to fight in a Union regiment. For two years Phin's mother waited. Then one day she told Nan Lundy, “He'll not come home.”

“You've heard nothing.”

“I've heard.” She'd had a hundred nightmares about him, she said, and then one quiet little dream like a telegram that she knew was true. And it must have been, because he never did come back.

The hoofbeats were louder. Phin glanced over his shoulder. The houses blocked his view. Hopefully that

worked both ways. He pulled his cap down and hurried on. Though he was vaguely aware of women in doorways, no one called his name. When his mother moved to Murray's, where she could feed her boy on what she earned as a laundress, keep him out of the breaker and the mine, she'd lost most of her respectable friends. Too young, too pretty, to go live in a saloon. Even if she'd been a toothless crone, it would have been a little scandalous. Only Nan Lundy was left, down on her luck these days and living here, in the last shack in Widow's Row, behind the flimsiest gate.

Phin pushed through and shut it behind him, and his legs took a running step all on their own. Just one. There were eyes everywhere, even here in the Lundys' yard. Walk.

The door stood open, daylight being cheaper than lamp oil. Mr. Lundy sat in his chair, knife flashing steadily as he carved a continuous chain out of an ash log. Phin blundered up the path, half falling. Lundy lifted his round dark eyes.

Don't

, the eyes said.

Don't bring trouble to this house.

The clear, silent message shocked Phin awake. Lundy'd been crippled in the mine. With six children to support, his wife wore herself out washing other men's clothes. Phin couldn't add to their burden.

Anyway, hadn't the AOH given the Lundys money, after the accident? The Ancient Order of Hiberniansârespectable, legal, organized for charity and to protect Irish rightsâand connected some way with the Sleepers. Phin had to be careful even here.

“I'm leaving.” His words surprised him. Inside, Mrs. Lundy turned from her enormous heap of laundry. “I stopped to say good-bye.”

“And where, so sudden?” Nan Lundy came out, drying her reddened hands on her apron. “D'you have someone to go to? Did Mary's relatives write?”

It was an old dream of his mother'sâthe letter, and him walking east and taking ship to Ireland. He should see it, his mother said, and England, too, choose for himself, not just stick to the choices his parents had made. Her uncle would come into money someday, and then it might be possible to live in Ireland.

Mrs. Lundy opened her mouth, took a quick breath as she tried to marshall her questions. Then she glanced sharply at Phin and went to stand by her husband's chair, putting one hand on his shoulder.

Lundy's slow eyes looked Phin up, looked him down. No coat. No bundle. Shirt thin and ragged, breath coming hard, and whatever showed on his face. Phin had no idea

what that was. His mouth felt like it was smiling and his back prickled. He kept twisting to glance over his shoulderâ

“Step inside,” Lundy said. “That piece of bacon, Nan. And cold biscuitâhaven't we got some cold biscuit?”

“Justâ” She didn't finish. Just that for your dinner, is what she would have said.

“Matches,” said Lundy. “On a journey like that, you'll want matches.” He reached down beside his chair and brought up one of the many cylindrical boxes he had carved.

His wife counted out the precious matchsticks, hesitated, her hand hovering over the box, then hastily added two more. Just so she and Phin's mother used to help each other, giving greatly on washerwomen's earnings.

Lundy unfastened the bandanna from his neck. His wife tied it around the biscuits, the matchbox, and a small lump of bacon she'd cut off a not-much-larger chunk. She gave Phin the bundle.

“Cut yourself a stick when you get out into the countryside,” Lundy said. “Got a knife, do you?”

Quickly, so he'd be believed, Phin nodded, glancing over his shoulder again. The Lundys had just one knife. She'd borrowed it from him to cut the bacon.

“Wish you had a bottle for water,” Mrs. Lundy said.

“You'll get thirsty, walking. But Jimmy's got all his father's kit now.”

Jimmy Lundy, swallowed underground; his little brothers swallowed into the breaker building, picking slate out of anthracite coal. If only Phin had been swallowed, too. If only he'd been safe underground this morning.

Dogs barked near the Street, as if at an intruder. Lundy jerked his head toward the back room. It had no door to the outside, but the window was wide open, letting in air and mosquitoes.

Mrs. Lundy darted ahead of Phin and came back carrying Mikkeleen, the littlest boy, pressing his face into her neck so he couldn't see, couldn't tell. “Go,” she mouthed, and leaned to kiss Phin, a hard, dry brush against his cheek. She turned away as Mikkeleen squirmed sleepily.

Phin slipped into the back room and was reaching for the windowsill when a sound froze himâmetal striking stone. Mikkeleen said, “Horsie?”

Phin turned around. Mrs. Lundy stood in the front doorway with Mikkeleen in her arms, filling it, blocking the light.

“I can't come to the gate,” she said loudly. “The child's sick, and my husband as well.” Her tone held the rider at a distance. A little distance; it was a little yard.

“Did a boy come this way?” The voice seemed familiar, but Phin couldn't place it. His life was full of men's voices, calling for drinks or a fresh pack of cards.

Nan Lundy said, “What would a boy be doing abroad, and the sun up already?” The Irish way; answer a question with a question, and you've told no lie. But who could she be talking to?

The man at the gate said, “This boy killed John Engelbreit, the supervisor. Or so they say.”

Her back went rigid. She glanced down at her husband. He nodded, jaw jutting. “We heard shots,” he said in a carrying voice. “What boy?”

“Chase, I think? Works in Murray's.”

Who

was

that? The voice was at once familiar and unknownâlike the whole world, this morning. Reality slipping; the way land went liquid beneath your feet when it was undermined.

“What's your interest?” Mr. Lundy asked.

“Murder's everybody's interest, isn't it? I was told the lad came this way.”

Lundy sat unmoving. From the shadowed inner room, Phin saw his profile and the bulk of his shoulder, edged with light.

“I was told wrong, then?”

“It would seem that way, wouldn't it?”

“How do I get up on that hill behind the houses? Is there a trail through here?”

“And why would you be wanting to ride on that hill at all?” Lundy asked. “Can the beast fly, that you'd risk him falling down one of those holes?”

“He can about fly, right enough,” the man said. A laugh warmed his voice, and for a second Phin almost knew him. “But thanks for the advice.”

The dogs took up their barking again. The children began to shout. As the hoofbeats receded, Phin gripped his bundle in his teeth, scrambled up the wall, and eeled through the window into the blackberry and goldenrod. He was running before he hit the ground.

Mistake. He knew it, but couldn't stop himself. Brambles caught him, clawed and slashed and whipped, but he tore through them, wanting only to get away, far awayâ

Black yawned under him and his foot came down on nothing, down and down and down.