Chatham Dockyard (23 page)

Authors: Philip MacDougall

Paving the way for these later far-reaching changes were a number of adaptations to shipbuilding design and constructional methods that started to be introduced towards the end of the Napoleonic Wars. Among them was a system of strengthening the frame of a ship through the timbers being braced together by trusses laid diagonally, and forming a series of triangles rather than the existing method of laying frame timbers in a square and rectangular pattern. A method invented by Robert Seppings, and brought to perfection following his appointment in 1804 to the office of Master Shipwright at Chatham, its importance was that of countering a tendency for the keels of larger ships to arch. Technically known as ‘hogging’ it resulted from the irregularity, when at sea, of the weight occasioned by greater upward pressure placed on the centre of the keel when compared with the extremities. At Chatham,

Kent

, a seventy-four-gun third rate, while under repair and known for her tendency to warp along the keel, was the first ship to which this method was applied. Later, in 1810, Seppings was given permission to use the same system in

Tremendous

, but this time he also included cross pieces between the various gun ports and additional timbers in the spaces between the lower frames.

Howe

, a 120-gun first rate, launched at Chatham in March 1815, was the first ship laid down and wholly built on the diagonal principle.

Unicom

, a fifth-rate frigate and now a museum ship at Dundee, was launched at Chatham in 1824. The interior of the vessel is of particular importance, revealing the extensive use of iron work to replace knees and other supporting timbers.

A second improvement pioneered by Seppings during his period at Chatham as Master Shipwright was that of giving larger ships a round bow. This had the advantage of improving the strength of the ship while providing an enlarged area of space for the mounting of guns in this, a traditionally under-gunned area of a warship. Following the conclusion of the Napoleonic Wars, most ships under construction and vessels undergoing major repair were provided with this new design feature as laid down in June 1816 by the following instructions issued to the shipwright officers at Chatham:

The Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty having by their Order of the 13th inst. approved of the general adoption of the round stern suggested by Commissioner Seppings in the construction of His Majesty’s ships. These are to direct and acquaint you, pursuant to their Lordships’ directions, to cause all ships of the line and frigates to be built with round sterns accordingly and also to put round sterns to such as may be repaired provided the repair may be such an extent as to justify the alteration. To enable you to do which, drawings are in preparation and will be sent to you for your guidance.

1

By March 1822, a total of fifteen warships had either been newly built or converted at Chatham to the new arrangement. Members of the Board of Admiralty during an inspection of the yard at Chatham, some two years earlier, had made a point of commenting on the conversion of ships to the round stern:

The

Trafalgar

and

Prince Regent

, building in this yard, were inspected, particularly with regard to the formation of their sterns. Some observations were made with regard to the angles, which may be formed in pointing the guns in the after part of both ships, and the advantages of those in the ship with the round stern were very manifest. The ships appeared in excellent condition and the timbers well seasoned.

2

At this period of time, both the Admiralty and Navy Board constantly expressed their concern at the need to examine methods that would not only provide greater strength to ships but also ensure that the timbers employed in their construction were more effectively seasoned and so less likely to be subjected to rot. A flavour of some of the other changes recently introduced into methods of shipbuilding practised at Chatham and the other royal dockyards, can be gained from this communiqué sent by the Navy Board to the Admiralty and explaining that considerable efforts were being made in these two areas of joint concern:

When ships are set up on the slips exposed to the weather, the Spring has been chosen as the best time for commencing operations in planking, the caulking of the wales and bottom has been deferred until the ships have been about to be launched and the painting (except upon the weather works) has been postponed as long as possible. The precaution of a temporary housing in midships and every other means of keeping the ships dry by caulking the topside weather decks &c have also been resorted to.

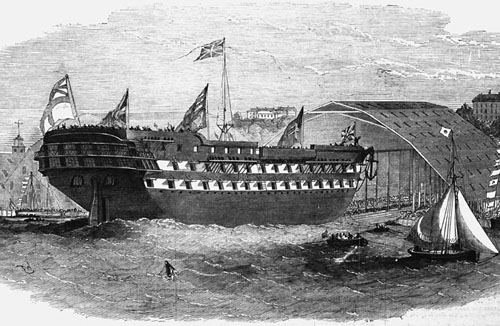

Another change to ships being built at Chatham during the middle years of the nineteenth century was the introduction of steam power, with the lauch of one such vessel,

Cressy

, an eighty-gun screw ship, taking place in July 1853, seen in an illustration that originally appeared in the

Illustrated London News

.

To promote a circulation of air for the seasoning of the timber, a great proportion of the treenails has been omitted as long as possible, some strakes of plank left out, wind sails introduced into the hold and louvred boards fitted in the ships’ ports. The system of covering over the docks and slips, which has been of late partially introduced, will no doubt effectively contribute to the duration of ships built and repaired by sheltering the frames as well as the converted materials and it will not only add to the comfort of the workmen but will also afford considerable facility in building and repairing ships. The rapid decay, which of late years has taken place in many ships built and repaired in the King’s and Merchant Yards, may be attributed to the following causes: the want of a sufficient store of seasoned timber, the scarcity of English oak (a great difficulty which has rendered it necessary to substitute fir timber) and the necessity of fitting newly built and repaired ships for service without allowing sufficient time for seasoning them and also the want of a sufficient number of slips and docks at the dockyards to meet the increased demand for ships of war and to permit the frames &c to stand a sufficient time to season.

Within a few years several important changes have taken place in the mode of constructing ships that we expect will be found not only to give strength to the fabric but prevent premature decay by affording a free circulation of air in the upper parts, but this is not likely to be attended to with the important advantages expected, if care be not taken (when the ships are in commission) to keep the shelf pieces clear and the openings free from dirt, as has been done while they were building.

3

These earlier changes to ship constructional methods, although considered radical at the time, were relatively insignificant when compared with the subsequent introduction of steam machinery into the hulls of warships combined with the eventual replacement of timber hulls with those of iron. In adapting to the use of steam as a motive power for warships, the workforce at Chatham was aided by their accumulated familiarity with the use of steam in certain of the manufacturing areas of the yard. By 1814, as already detailed, it had been introduced into the saw mill with a steam pump also having been introduced into the yard for the purpose of draining an increasing number of dry docks. Furthermore, steam was also being used afloat, steam dredgers now employed in clearing the channels of the river of those fast-accumulating mud shoals.

It was in May 1831 that the first steam vessel was laid down at Chatham, a timber-hulled paddle sloop named

Phoenix

. An event of considerable importance, she was one of four paddle steamers built in the naval dockyards at this time, the four vessels being among the largest and most powerful of the day. Each was the product of a different senior shipwright employed by the Navy Board, with

Phoenix

designed by Robert Seppings who, by that time, was serving out his final years as Surveyor of the Navy. Another former Master Shipwright at Chatham, John Fincham, explained the reasons that lay behind this particular decision to concurrently build four independently designed vessels:

The importance of employing steam-vessels led now to the adoption of measures calculated to improve their character. The Admiralty desired to engage all the talents in the service with the view to this end, and invited the several Master Shipwrights to send in plans which they respectively deemed best suited for steam vessels.

4

To this Fincham added:

It is no disparagement of the talents of their respective constructors to say that these vessels shared in the imperfections which were almost necessary at a time when the conditions of excellence in steam-vessels were only in the course of development; at the same time it is fair and just to say, that they were all useful vessels, and they have been durable and permanent in their usefulness.

5

In having decided that these vessels were to be built in the royal dockyards, the Admiralty was sending out a clear message that the private yards were no longer to have a monopoly in this area of shipbuilding. As for the fitting of engines, Chatham still had a clear area of weakness, newly constructed steamers having often to be towed to one of the several specialist marine engine constructors located along the banks of the river Thames.

Phoenix

, for her part, following her floating out of dry dock in September 1831 was taken to Lambeth where Maudslay, Son & Field were responsible for both constructing and fitting her engine. For this, they charged the Admiralty £10,781 for the machinery and a further £7,968 for its installation, with the total cost of the vessel amounting to £33,463.

From this initial experience, Chatham went on to build a total of nineteen paddle steamers, with the last of these a sixteen-gun sloop named

Tiger

, launched in 1849 and fitted with a 400nhp engine built by John Penn & Son at their Deptford yard. During those years of constructing paddle steamers, Chatham had taken on an increasing amount of work connected with the steam machinery, fitting the engines of some and acquiring the skills to construct and modify boilers and paddle wheels. In addition, the workforce at Chatham oversaw the conducting of trials upon vessels once the machinery had been installed.

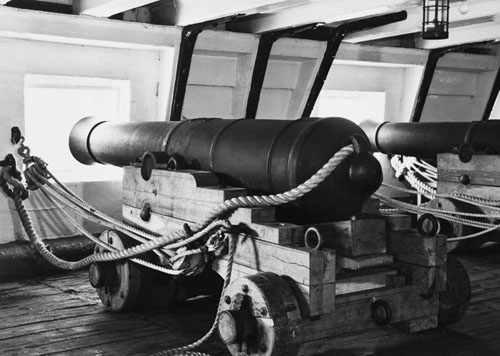

A further important landmark for Chatham was the building of

Bee

, a composite vessel fitted with both paddle wheels and an underwater screw and both working off the same machinery. Launched in February 1842, she was very much an experimental vessel, designed to assess the screw as a means of propelling a vessel through water. While paddle steamers had proved themselves useful, towing large sailing ships in unsuitable winds or for the more rapid carriage of troops and supplies, they had only limited value as warships. Primarily this was because of the large paddle wheels that sat on either side, these having an immense vulnerability to canon fire while also restricting the number of guns that could be fitted. In moving away from the use of paddles and replacing them with an underwater screw, much experimental work was required, with

Bee

having an important part to play in this work. Not only did she permit those who crewed her to learn the characteristics of a screw-propelled ship but she also permitted a direct comparison

to be made between the two types of propellants. Indeed, she had been so designed that paddles and screw could work in opposition, allowing a direct comparison to be undertaken and demonstrating with regards to this particular vessel that the paddle could continue to drive the vessel forward despite the screws running in reverse. According to one more recent commentator, ‘this must surely be the most bizarre trial of all time!’

6