Chicken Soup for the Kid’s Soul (4 page)

Read Chicken Soup for the Kid’s Soul Online

Authors: Jack Canfield

L

ove is something eternal.

Vincent van Gogh

Dad brought him home from a fishing trip in the mountains, full of cockleburs and so thin you could count every rib.

“Good gracious,” Mom said. “He’s filthy!”

“No, he isn’t! He’s Rusty,” said John, my eight-year-old brother. “Can we keep him? Please . . . please . . . please.”

“He’s going to be a big dog,” Dad warned, lifting a mudencrusted paw. “Probably why he was abandoned.”

“What kind of dog?” I asked. It was impossible to get close to this smelly creature.

“Mostly German shepherd,” Dad said. “He’s in bad shape, John. He may not make it.”

John was gently picking out cockleburs.

“I’ll take care of Rusty. Honest, I will.”

Mom gave in, as she usually did with John. My little brother had a mild form of hemophilia. Four years earlier, he’d almost bled to death from a routine tonsillectomy. We’d all been careful with him since then.

“All right, John,” Dad said. “We’ll keep Rusty. But he’s your responsibility.”

“Deal!”

And that’s how Rusty came to live with us. He was John’s dog from that very first moment, though he tolerated the rest of us.

John kept his word. He fed, watered, medicated and groomed the scruffy-looking animal every day. I think he liked taking care of something rather than being taken care of.

Over the summer, Rusty grew into a big, handsome dog. He and John were constant companions. Wherever John went, Rusty was by his side. When school began, Rusty would walk John the six blocks to elementary school, then come home. Every school day at three o’clock, rain or shine, Rusty would wait for John at the playground.

“There goes Rusty,” the neighbors would say. “Must be close to three. You can set your watch by that dog.”

Telling time wasn’t the only amazing thing about Rusty. Somehow, he sensed that John shouldn’t roughhouse like the other boys. He was very protective. When the neighborhood bully taunted my undersized brother, Rusty’s hackles rose, and a deep, menacing growl came from his throat. The heckling ceased after one encounter. And when John and his best friend Bobby wrestled, Rusty monitored their play with a watchful eye. If John were on top, fine. If Bobby got John down, Rusty would lope over, grab Bobby’s collar and pull him off. Bobby and John thought this game great fun. They staged fights quite often, much to Mother’s dismay.

“You’re going to get hurt, John!” she would scold. “And you aren’t being fair to Rusty.”

John didn’t like being restricted. He hated being careful— being different. “It’s just a game, Mom. Shoot, even Rusty knows that. Don’t you, boy?” Rusty would cock his head and give John a happy smile.

In the spring, John got an afternoon paper route. He’d come home from school, fold his papers and take off on his bike to deliver them. He always took the same streets, in the same order. Of course, Rusty delivered papers, too.

One day, for no particular reason, John changed his route. Instead of turning left on a street as he usually did, he turned right. Thump! . . . Crash! . . . A screech of brakes . . . Rusty sailed through the air.

Someone called us about the accident. I had to pry John from Rusty’s lifeless body so that Dad could bring Rusty home.

“It’s my fault,” John said over and over. “Rusty thought the car was gonna hit me. He thought it was another game.”

“The only game Rusty was playing was the game of love,” Dad said. “You both played it well.”

John sniffled. “Huh?”

“You were there for Rusty when he needed you. He was there for you when he thought you needed him. That’s the game of love.”

“I want him back,” John wailed. “My Rusty’s gone!”

“No, he isn’t,” Dad said, hugging John and me. “Rusty will stay in your memories forever.”

And he has.

Lou Kassem

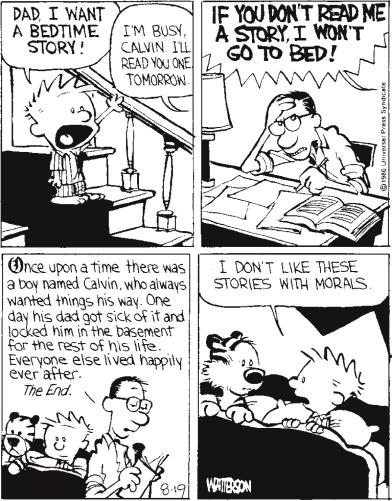

©CALVIN AND HOBBES. Distributed by Universal Press Syndicate. Reprinted with permission. All rights reserved.

There once was a little girl named Cindy. Cindy’s father worked six days a week, and often came home tired from the office. Her mother worked equally hard, doing the cleaning, the cooking and the many tasks needed to run a family. Theirs was a good family, living a good life. Only one thing was missing, but Cindy didn’t even realize it.

One day, when she was nine, she went on her first sleepover. She stayed with her friend Debbie. At bedtime, Debbie’s mother tucked the girls into bed. She kissed them both good night.

“Love you,” said Debbie’s mother.

“Love you, too,” murmured Debbie.

Cindy was so amazed that she couldn’t sleep. No one had ever kissed her good night. No one had ever kissed her at all. No one had ever told her that they loved her. All night long, she lay there, thinking over and over,

This is the way it should be.

When she went home, her parents seemed pleased to see her.

“Did you have fun at Debbie’s house?” asked her mother.

“The house felt awfully quiet without you,” said her father.

Cindy didn’t answer. She ran up to her room. She hated them both. Why had they never kissed her? Why had they never hugged her or told her they loved her? Didn’t they love her?

She wished she could run away. She wished she could live with Debbie’s mother. Maybe there had been a mistake and these weren’t her real parents. Maybe Debbie’s mother was her real mother.

That night before bed, she went to her parents.

“Well, good night then,” she said. Her father looked up from his paper.

“Good night,” he said.

Her mother put down her sewing and smiled. “Good night, Cindy.”

No one made a move. Cindy couldn’t stand it any longer.

“Why don’t you ever kiss me?” she asked.

Her mother looked flustered. “Well,” she stammered, “because, I guess . . . because no one ever kissed

me

when

I

was little. That’s just the way it was.”

Cindy cried herself to sleep. For many days she was angry. Finally she decided to run away. She would go to Debbie’s house and live with them. She would never go back to the parents who didn’t love her.

She packed her backpack and left without a word. But once she got to Debbie’s house, she couldn’t go in. She decided that no one would believe her. No one would let her live with Debbie’s parents. She gave up her plan and walked away.

Everything felt bleak and hopeless and awful. She would never have a family like Debbie’s. She was stuck forever with the worst, most loveless parents in the world.

Instead of going home, she went to a park and sat on a park bench. She sat there for a long time, thinking, until it grew dark. All of a sudden, she saw the way. This plan would work. She would make it work.

When she walked into her house, her father was on the phone. He hung up immediately. Her mother was sitting with an anxious expression on her face. The moment Cindy walked in, her mother called out, “Where have you been? We’ve been worried to death!”

Cindy didn’t answer. Instead she walked up to her mother, gave her a kiss right on the cheek and said, “I love you, Mom.” Her mother was so startled that she couldn’t speak. Cindy marched up to her dad. She gave him a hug. “Good night, Dad,” she said. “I love you.” And then she went to bed, leaving her speechless parents in the kitchen.

The next morning when she came down to breakfast, she gave her mother a kiss. She gave her father a kiss. At the bus stop, she stood on tiptoe and kissed her mother.

“Bye, Mom,” she said. “I love you.”

And that’s what Cindy did, every day of every week of every month. Sometimes her parents drew back from her, stiff and awkward. Sometimes they laughed about it. But they never returned the kiss. But Cindy didn’t stop. She had made her plan. She kept right at it. Then, one evening, she forgot to kiss her mother before bed. A short time later, the door of her room opened. Her mother came in.

“Where’s my kiss, then?” she asked, pretending to be cross.

Cindy sat up. “Oh, I forgot,” she said. She kissed her mother.

“I love you, Mom.” She lay down again. “Good night,” she said and closed her eyes. But her mother didn’t leave. Finally she spoke.

“I love you, too,” her mother said. Then her mother bent down and kissed Cindy, right on the cheek. “And don’t ever forget my kiss again,” she said, pretending to be stern.

Cindy laughed. “I won’t,” she said. And she didn’t.

Many years later, Cindy had a child of her own, and she kissed that baby until, as she put it, “Her little cheeks were red.”

And every time she went home, the first thing her mother would say to her was, “Where’s my kiss, then?” And when it was time to leave, she’d say, “I love you. You know that, don’t you?”

“Yes, Mom,” Cindy would say. “I’ve always known that.”

M. A. Urquhart

Adapted from an Ann Landers column

There isn’t much that I can do,

But I can share an hour with you,

And I can share a joke with you. . . .

As on our way we go.

Maude V. Preston

Every Saturday, Grandpa and I walk to the nursing home a few blocks away from our house. We go to visit many of the old and sick people who live there because they can’t take care of themselves anymore.

“Whoever visits the sick gives them life,” Grandpa always says.

First we visit Mrs. Sokol. I call her “The Cook.” She likes to talk about the time when she was a well-known cook back in Russia. People would come from miles around, just to taste her famous chicken soup.

Next we visit Mr. Meyer. I call him “The Joke Man.” We sit around his coffee table, and he tells us jokes. Some are very funny. Some aren’t. And some I don’t get. He laughs at his own jokes, shaking up and down and turning red in the face. Grandpa and I can’t help but laugh along with him, even when the jokes aren’t very funny.

Next door is Mr. Lipman. I call him “The Singer” because he loves to sing for us. Whenever he does, his beautiful voice fills the air, clear and strong and so full of energy that we always sing along with him.

We visit Mrs. Kagan, “The Grandmother,” who shows us pictures of her grandchildren. They’re all over the room, in frames, in albums and even taped to the walls.

Mrs. Schrieber’s room is filled with memories, memories that come alive as she tells us stories of her own experiences during the old days. I call her “The Memory Lady.”

Then there’s Mr. Krull, “The Quiet Man.” He doesn’t have very much to say; he just listens when Grandpa or I talk to him. He nods and smiles, and tells us to come again next week. That’s what everyone says to Grandpa and me, even the woman in charge, behind the desk.

Every week we do come again, even in the rain. We walk together to visit our friends: The Cook, The Joke Man, The Singer, The Grandmother, The Memory Lady and The Quiet Man.

One day Grandpa got very sick and had to go to the hospital. The doctors said they didn’t think he would ever get better.

Saturday came, and it was time to visit the nursing home. How could I go visiting without Grandpa? Then I remembered what Grandpa once told me: “Nothing should stand in the way of doing a good deed.” So I went alone.

Everyone was happy to see me. They were surprised when they didn’t see Grandpa. When I told them that he was sick and in the hospital, they could tell I was sad.

“Everything is in God’s hands,” they told me. “Do your best and God will do the rest.”

The Cook went on to reveal some of her secret ingredients. The Joke Man told me his latest jokes. The Singer sang a song especially for me. The Grandmother showed me more pictures. The Memory Lady shared more of her memories. When I visited The Quiet Man, I asked him lots of questions. When I ran out of questions, I talked about what I had learned in school.

After a while, I said good-bye to everyone, even the woman in charge, behind the desk.

“Thank you for coming,” she said. “May your grandfather have a complete recovery.”

A few days later, Grandpa was still in the hospital. He was not eating, he could not sit up and he could barely speak. I went to the corner of the room so Grandpa wouldn’t see me cry. My mother took my place by the bed and held Grandpa’s hand. The room was dim and very quiet.

Suddenly the nurse came into the room and said, “You have some visitors.”

“Is this the place with the party?” I heard a familiar voice ask.

I looked up. It was The Joke Man. Behind him were the Cook, The Singer, The Grandmother, The Memory Lady, The Quiet Man and even the woman in charge, behind the desk.

The Cook told Grandpa about all the great food that she would cook for him once he got well. She had even brought him a hot bowl of homemade chicken soup.

“Chicken soup? What this man needs is a pastrami sandwich,” said The Joke Man as he let out one of his deep, rich laughs.

Everyone laughed with him. Then he told us some new jokes. By the time he was finished, everyone had to use tissues to dry their eyes from laughing so hard.

Next, The Grandmother showed Grandpa a get-well card made by two of her granddaughters. On the front of one card was a picture of a clown holding balloons. “Get well soon!” was scribbled in crayon on the inside.

The Singer started singing, and we all sang along with him. The Memory Lady told us how Grandpa once came to visit her in a snowstorm, just to bring her some roses for her birthday.

Before I knew it, visiting hours were up. Everyone said a short prayer for Grandpa. Then they said good-bye and told him that they would see him again soon.

That evening, Grandpa called the nurse in and said he was hungry. Soon he began to sit up. Finally he was able to get out of bed. Each day, Grandpa felt better and better, and he grew stronger and stronger. Soon he was able to go home.

The doctors were shocked. They said his recovery was a medical miracle. But I knew the truth: His friends’ visit had made him well.

Grandpa is better now. Every Saturday, without fail, we walk together to visit our friends: The Cook, The Joke Man, The Singer, The Grandmother, The Memory Lady, The Quiet Man . . . and the woman in charge, behind the desk.

Debbie Herman