Chicken Soup for the Soul: Children with Special Needs (19 page)

Read Chicken Soup for the Soul: Children with Special Needs Online

Authors: Jack Canfield

Then I got married, moved away, and had children. In some ways, I had left my military childhood behind. I no longer knew exactly when my dad was out on detachment or home with Mom. In 1994, Colonel Tace died of a massive heart attack while serving overseas and never came home.

No one could have anticipated the strength and support of the greater military family that would keep them going. No one could have anticipated the way Marc would rise to the occasion and become the father figure for his family. And no one anticipated—although we should have—the way the Marines would take care of their own and embrace Marc and his family.

Last week, more than ten years after Colonel Tace’s death, it was that same strength and support that cradled Mrs. Tace when she laid Marc to rest next to his dad.

With an American flag in one hand and the Marine Corps flag in the other, Mrs. Tace kissed her son’s coffin and told him, “Don’t be afraid. I’m here with you.” Then, coincidentally, a military jet from nearby Naval Air Station Oceana screeched overhead, rustling the flaps of the tent where we stood. I imagined Col. Tace, from somewhere up above, smiling at the timing of those jets. I thought,

Leave it to a Marine to arrange a flyby for his son’s funeral.

On June 19, muscular dystrophy finally took Marc Tace’s life, just a few months shy of his thirtieth birthday. Yet in some way, death also freed Marc because the morning Mrs. Tace found her son lying still in his bed wasn’t any ordinary day. No, the day Marc slipped from this life to the next, to find what he’d been waiting for, was Father’s Day.

And so it was, on the day set aside for fathers and their children, Marc went home to be with his dad, where this time the Marine stood waiting for his son. Semper Fi.

Sarah Smiley

Sarah Smiley

is the author of

Shore Duty,

a syndicated newspaper column, and the book,

Going Overboard.

Sarah’s book was optioned by Kelsey Grammer’s company, Grammnet, and Paramount Television. It is now in development to be a half-hour sitcom for CBS. To learn more about Sarah, please visit

www.sarahsmiley.com

.

I

was one of the “puzzle children” myself—a dyslexic . . . And I still have a hard time reading today. Accept the fact that you have a problem. Refuse to feel sorry for yourself. You have a challenge; never quit!

Nelson Rockefeller

It was October 25, 1881, in Malaga, Spain. Two men sat comfortably chatting, waiting for the birth of a baby upstairs. When the midwife came in, she looked troubled, and when she started to speak, she cast her glance toward the floor. “I’m sorry, the baby was stillborn.”

One of the men, the baby’s uncle and a physician, put down his cigar and got up. He walked quickly up the stairs. He picked up his tiny nephew, unmoving and blue. Without hesitation, he brought the lifeless infant close to his face as if to kiss him and breathed into his mouth. The first breath that filled the baby’s tiny lungs was still heavily scented with cigar smoke.

The baby’s mother had already entered the dark recesses of her grief as she looked on in fear and wonder as her son took a struggling breath. Could she dare to hope that her baby might yet be saved? She had hoped for a healthy child, one who would live a full and normal life. She still wanted that. The story of the doctor who breathed life into a dead baby spread around the city. Some said it was unholy; others thought it might have been a miracle. Many thought it was foolish. Was it right to interfere with nature? Did the uncle’s rash actions just delay the inevitable? Would this infant ever grow into a normal human being or contribute to society? Might it have been better to accept fate and simply let nature take its course? Yet, when the next day came, the baby was still breathing.

Soon, days became weeks, and weeks became years. Eventually, he learned to walk and talk, and to do many of the same things that other children do. He even learned to draw and paint. Of course, some people laughed when he would put the eyes in the wrong place or make silly mistakes on other details, but other people actually thought his drawings were quite good.

As it turned out, the uncle’s action had only delayed the inevitable, and eventually the baby whose life was saved in the fall of 1881 died in 1973, but the art that Pablo Picasso created lives on.

Some people claim that his lifelong love for cigars started with that first breath. Picasso’s story is about an uncle’s hope. In a moment in which others might have only seen despair, Picasso’s uncle had a moment of hope. His family was rewarded with a healthy child, and Picasso’s genius transformed the world of art. It shows that great things can come from what seem like catastrophic beginnings, and a moment of hope can transform the world.

Dick Sobsey

Dick Sobsey

is director of the JP Das Developmental Disabilities Centre and the John Dossetor Health Ethics Centre in Edmonton, Canada. Like Pablo Picasso, Dick was diagnosed later in life as having dyslexia. Unlike Picasso, he has no artistic talent and very little affection for cigars.

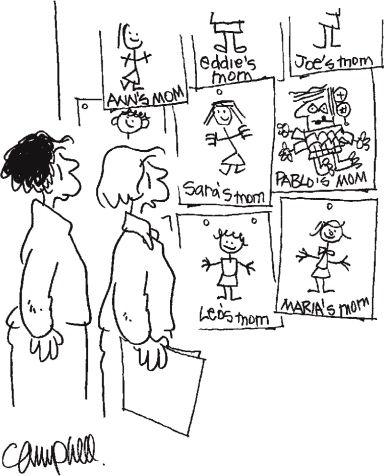

“I really hope Mrs. Picasso comes to Parents’ Night.”

Reprinted by permission of Martha F. Campbell. ©2006 Martha Campbell.

T

here is no chance, no destiny, no fate that

can circumvent or hinder or control the

firm resolve of a determined soul.

Ella Wheeler Wilcox

G

od

is

the answer. What is the question?

Jay Robb

Duringmy pregnancy there had been no sign of anything wrong with the baby. I took my vitamins, ate lots of fruits and vegetables, and did my stretching exercises. I expected everything would go as smoothly as they had when my first son was born: an easy delivery and a “perfect” child.

In the delivery room, squeezing my husband’s hand and hearing our baby’s first cry, I was not prepared for what followed. The look on the nurse’s face expressed her alarm as clearly as her words: “Mrs. Gardner, something’s wrong here!” I looked in horror as she pulled back the blanket to show our son’s face: one eye sealed shut; the other a milky mass; no bridge to his nose, and a face that looked crushed. Although I knew I should take him in my arms, I couldn’t. I just couldn’t. He was whisked away by the nurse as I was wheeled to the recovery room.

I lay on the hard hospital bed, the tightly pulled curtain shutting out the world. Still, I could hear other new mothers cooing to their babies. I heard one bemoan, “Not another boy!” and I was filled with jealous rage.

I thought of all the dreams I’d had for this child, of cuddling with him, of reading to him from brightly colored picture books, of his singing or painting or playing the piano like his older brother Jamaal—of his eyes, like Jamaal’s, studying the keys.

Instead, my baby was blind and painful to look at.

Slowly, deliberately I walked to the phone and dialed my mom. My agony poured out between sobs: “It’s a boy. His eyes won’t open. His face is deformed. Mom, what am I going to do?”

“You will bring him home. You will bring him home and nurture him,” she replied simply, firmly.

A nurse appeared at my side, led me to a rocker, and placed a small, blanketed bundle in my arms. Taking a deep breath, I looked down at my son. I had hoped he would look different—but he didn’t. His forehead protruded. Under the sealed eyelid, an eyeball was missing, the other was spaced far from it. His bridgeless nose was bent to the side of his face. The doctors called it

hypertelorism.

I didn’t know what to call it.

As we rocked, my mom’s words echoed in my ears. I began to talk to him. “Hello, Jermaine,” I said. “That’s your name. I am your mommy, and I love you. I’m sorry I waited so long to come to you and to hold you. Please forgive me. You have a big brother and a wonderful father who also love you. I promise to work hard to make your life the best it can be. Your grandpa has a lovely voice, and can play the piano and sing. I can give you music.”

Yes,

I thought,

that I can do. That I will do!

Over the next few months, my husband and I poured our energies into filling up the darkness in Jermaine’s life. One of us carried him in his Snugli or backpack at all times, constantly talking or singing to him. We inundated himwithmusic—mostly classical, some Lionel Richie, some Stevie Wonder. His four-year-old brother was already taking piano lessons, and whenever he practiced, I sat next to him on the piano bench with his little brother on my lap. After a while, I began strapping Jermaine into his high chair next to Jamaal when Jamaal practiced.

However, I seldom took Jermaine out of the house because I couldn’t stand anyone staring at my baby. Since blind infants cannot mimic a smile they cannot see, they often do

not smile. It hurt that I got no smiles from Jermaine.

Every day my younger sister, Keetie, called, reminding me that God had a plan for each of us.

One day, Jamaal was practicing the piano, playing “Lightly Row” again and again, his little brother secure in his high chair next to him. Jamaal had just finished practicing and had come downstairs where my husband and I were sitting, when we heard a familiar

plink plunk-plunk, plink plunk-plunk

floating down the stairs. I looked at my husband, and he looked at me. It couldn’t be Jamaal. He was jumping up and down on our bed. We stared at each other for a second, then tore upstairs!

At the piano, head thrown back, a first-ever smile splitting his face, Jermaine was playing “Lightly Row”! The right keys, the right rhythm, the right everything!

In response to my husband’s immediate and astonished, amazing-news phone calls, the house filled with family and friends within an hour. I sat Jermaine at the piano in his high chair, as we all stood around expectantly.

Nothing.

I hummed “Lightly Row” and played a few notes. Jermaine sat silent, his hands motionless.

“It was just a fluke,” my husband said.

“No,” I replied unabashed. “It couldn’t have been.” I was certain our eight-and-a-half-month-old son had perfectly replicated a tune.

Two weeks later, he did it again, this time playing another piece his older brother had practiced. I ran to the piano and listened as the notes became firmer and the tune melded into its correct form.

From then on, there was no stopping Jermaine. He demanded to be at the piano from morning until bedtime. I often fed him at the piano, wiping strained applesauce off the keys. At first, he only played Jamaal’s practice songs . . . and then he played Lionel Richie’s “Hello” after hearing it on the tape recorder. At eighteen months, he played the left-hand part of Beethoven’s “Moonlight Sonata” while my sister played the right-hand part. When he gave his first concert, I crawled under the piano to work the foot pedals his little legs could not possibly reach.

By the time he was out of diapers, I was desperate to find him a good piano teacher. I sought out a teacher at the Maryland School for the Blind and called, explaining that Jermaine was already playing the piano.

“How old is he?” the teacher asked.

“Two and a half,” I replied.

“A child that age is too young to start piano lessons,” he said disapprovingly, just as strains of “Moonlight Sonata” filtered in from the other room.