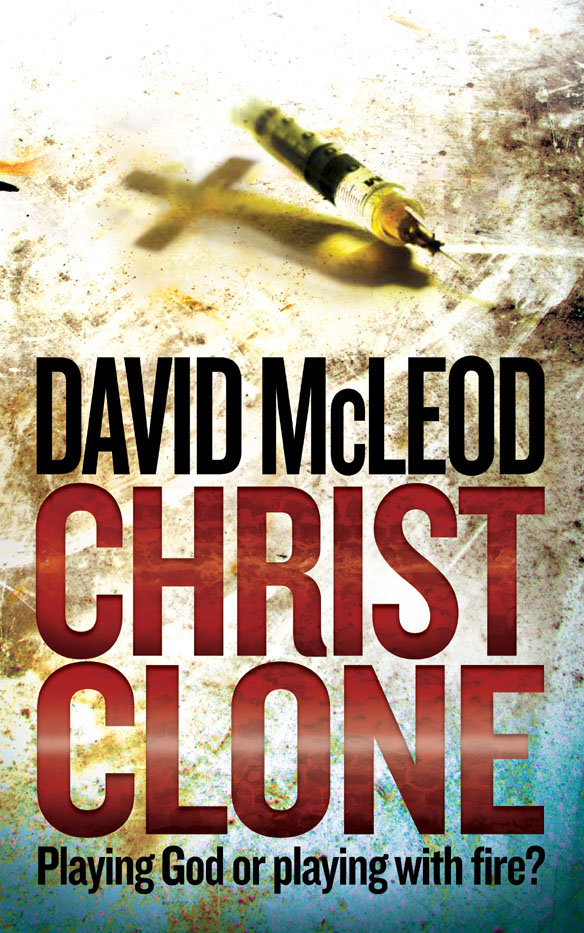

Christ Clone

Authors: David McLeod

- Title Page

- About the Author

- Acknowledgements

- Copyright Page

- Prologue

- Chapter 1

- Chapter 2

- Chapter 3

- Chapter 4

- Chapter 5

- Chapter 6

- Chapter 7

- Chapter 8

- Chapter 9

- Chapter 10

- Chapter 11

- Chapter 12

- Chapter 13

- Chapter 14

- Chapter 15

- Chapter 16

- Chapter 17

- Chapter 18

- Chapter 19

- Chapter 20

- Chapter 21

- Chapter 22

- Chapter 23

- Chapter 24

- Chapter 25

- Chapter 26

- Chapter 27

- Chapter 28

- Chapter 29

- Chapter 30

- Chapter 31

- Chapter 32

- Chapter 33

- Chapter 34

- Chapter 35

- Chapter 36

- Chapter 37

- Chapter 38

- Chapter 39

- Chapter 40

- Chapter 41

- Chapter 42

- Chapter 43

- Chapter 44

- Chapter 45

- Chapter 46

- Chapter 47

- Chapter 48

- Chapter 49

- Chapter 50

- Chapter 51

- Chapter 52

- Chapter 53

- Chapter 54

- Chapter 55

David McLeod

Born in Swindon, England, in 1967, David McLeod studied

electronics at Highbury and Brunel technical colleges but subsequently

worked mainly in sales and management positions. He

travelled extensively through Europe and the United States before

moving to New Zealand in 1994. He is an avid reader of fiction

and keen movie watcher. He visits his family in the UK annually,

stopping off at new destinations on the way. This is his first

novel.

With thanks to family, friends and Judi for their

assistance, support and belief

This eBook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author's and publisher's rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

ISBN 978 1869792336

Version 1.0

A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of New Zealand.

AN ARROW BOOK

published by

Random House New Zealand

18 Poland Road, Glenfield, Auckland, New Zealand

www.randomhouse.co.nz

Random House International

Random House

20 Vauxhall Bridge Road

London, SW1V 2SA

United Kingdom

Random House Australia (Pty) Ltd

20 Alfred Street, Milsons Point, Sydney,

New South Wales 2061, Australia

Random House South Africa Pty Ltd

Isle of Houghton

Corner Boundary Road and Carse O'Gowrie

Houghton 2198, South Africa

Random House Publishers India Private Ltd

301 World Trade Tower, Hotel Intercontinental Grand Complex,

Barakhamba Lane, New Delhi 110 001, India

First published 2008

© 2008 David McLeod

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

ISBN: 978 1869792336

Version 1.0

This electronic book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

Design: Katy Yiakmis

Cover illustration: PurestockX.com

Cover design: Matthew Trbuhovic, Third Eye Design

G

OLGOTHA

(S

KULL

H

ILL

), J

ERUSALEM

A

NNO

D

OMINI

33

The burning mid-afternoon sun bears down on Golgotha. The barren hill is situated just outside Jerusalem's city walls — walls that were put in place to protect the city from the rest of the world, keeping the good within and evil from entering.

Three crosses stand erect on top of the hill, casting short shadows on the arid ground. Each cross holds the failing body of a man sentenced to death — his crime proclaimed on a plaque above him for all to see.

One plaque reads FVR (thief), another has MVRDRATOR (murderer); the plaque on top of the middle cross reads INRI — an acronym for

IESVS NAZARENVS REX IVDAEORVM (Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews). A third of the way up the main trunk of this wooden cross are two blackened and bloody feet, one placed in front of the other in the position of a ballet dancer's

en pointe

. These feet, however, will never dance for they have been fixed in place with an iron nail that pierces the flesh, shattering the bones inside. Behind the wound, the thirsty wood of the cross has turned red as it absorbs the blood seeping from the wound. The man's chest is pulled taut, his arms spread wide as though in a welcoming gesture, his hands nailed to the crossbeam.

Every breath he takes inflicts agony; his heart is at bursting point from the pressure it is under. A crown of thorns rammed onto his head has made deep open cuts from which thick red rivulets have run down his face and congealed.

Below his cross a small crowd has assembled, some standing, some sitting. Their mockery has subsided, and a low mumble of talk can be heard along with the gentle sobs of a few. Among the crowd a bearded man stands still and silent. He is clothed in a dirty brown robe and wears dusty sandals. His head is tilted back as he stares up at the cross.

His lips are dry and cracked, and his mouth is open. His breathing is troubled and wheezy, evidence of the later stages of tuberculosis. The glaring sun is starting to burn the corneas of his eyes but he knows the sight before him will leave a deeper scar on his mind, erasing the discomfort he is feeling now.

'What have they done to you?' he whispers. 'Why are you here?

Have you achieved what you set out to do?' There are so many questions he wants to ask, but it is too late for answers now and he can only regret his lack of courage when the time was right.

The man on the cross is drifting in and out of consciousness; his head is hanging and the whites of his eyes are showing. As he regains consciousness, the colour in his eyes returns but he struggles to focus.

He seems to be responding to the man on the cross to his left; he whispers hoarsely to his fellow-sufferer, 'Verily I say to thee, today thou shalt be with me in paradise.' With all the strength he can muster, he lifts his head and looks skyward.

Witnessing his movement, silence falls on the small group of people below. There is a soft, rasping sound as the man on the central cross tries to lubricate his parched throat. The eyes of the group are fixed on him as his feeble voice strives to make itself heard. 'Forgive them,

Father, for they know not what they do.'

A dark cloud creeps across the sky and eclipses the sun; its presence casts a band of black shadow over the hill. As it does, so the last of

Jesus' life slips away, his head coming to rest on his blistered and lacerated chest.

A Roman centurion walks between the crosses with a sea sponge soaked in vinegar impaled on his spear. Coming to the cross of Jesus, the soldier presses the sponge into the bloody face. The lifeless body refuses to drink; the head bobs with each prod of the sponge. The soldier removes the sponge from the pole, exposing the vicious spearhead beneath, and he forces its sharp steel tip under Jesus' ribcage to confirm his death. As he pulls the spear from the body, there is the sound of wood snapping. The spearhead breaks from the standard and drops to the ground. Leaving the spearhead where it has fallen, the soldier moves on.

L

OS

A

NGELES

A

FEW YEARS FROM NOW

The Dog Box was an apt name for the small bar in the downtown area of Los Angeles. Apt because of its location in the gloomy basement of a building at the top of a dogleg road. The minute signage by the steps leading down to it was easy to miss, making it a haven for people who wanted to forget and be forgotten.

Michael Malone sat at the bar which ran the length of the room.

Malone wasn't bad-looking for forty-three, though years of alcohol abuse and lack of sunlight had bleached his skin and made him look older. The odours of stale beer and cigarette smoke permeated the room. The clientele was unhappy about the no-smoking regulations and the management didn't enforce them. A chat show was playing quietly on the TV behind the bar but no one was paying attention; people were there to drink, and they were there to forget.

Malone ordered another whisky to chase his half-empty beer.

'There ya go, Father,' the barman said as he filled Malone's shot glass. Malone loathed being called Father. He'd resigned from the priesthood a long time ago, but years of disputing his status with the barman hadn't made any difference, so he just accepted the drink.

Malone raised his drink to no one in particular and took a slug.

The warming liquid slipped gently down his throat to his belly, sending reassuring signals to his head. He looked at the losers lined up along the bar and was pleased not to be one of them. Two of them were trying to outdo one another with drunken lavatory humour.

'One time, when I went to the john I was surrounded by flies. They were all round my head. Wherever I looked, there they were. I swatted at them but I couldn't hit any. You know what? Turned out I was so drunk I was seeing stars, not flies.' Both men laughed.

'I can top that,' the other yelled excitedly. 'Once I was so drunk that when I came back to the bar after I'd been to relieve myself, everyone pointed at my pants. I'd pissed myself, and my shirt-tail was through my fly. I'd pulled my shirt through my fly thinking it was my dick, and held onto it as I pissed down my leg!'

Even Malone laughed at that. But almost immediately his mood turned melancholy again, and he returned to a world of his own where alcohol had numbed the pain of the past he carried with him always.

As he took another long slug of Scotch, he thought about his wife and how she'd been taken from him. He thought about his daughter and wished, as he had a million times before, that he knew where she was or what had happened to her. Finally, he thought about his own life and how much it had changed. Once a respectable priest and a loving husband and father, he was now just another drunk in a bar.

Snapping out of his thoughts, Malone lifted his glass and proposed another toast — to no one in particular. 'Here's to sobriety. May it never darken my door again!'

A grey-faced man returning from the restroom slapped Malone on the back and sat on a stool next to him. Before long they were deep in conversation, not necessarily with each other, but they both had points that needed to be reinforced by raising their voices and clinking their glasses together. These moments of connection were followed by long periods of silence and reflection.

The chat show on the TV behind the bar finished and was replaced by the day's news. The lead story showed a distraught couple being interviewed; the red-eyed husband and his wife were sitting too close to each other, holding hands. A drawing of a beige van flashed onto the screen and on the side of the van was the name, About Plumbing.

This caught Malone's attention.

'Quick, turn up the sound!' Malone snapped at the barman.

'What?'

'Turn up the fucking sound!' Malone yelled.

The barman grabbed the remote and flicked up the volume.

The reporter had returned to the couple and was asking more questions about their missing daughter.

A pretty Hispanic girl's face was filling the screen. Malone froze at the sight of her name — Mary Salinas — below the image.

'What's the matter? You look like you've seen a ghost,' the barman said. He actually seemed concerned.

'I've got to go!' Malone threw a fifty on the bar and raced outside, where he hailed a cab and gave the driver his home address.

Malone hated his home in Mission, East Los Angeles. Mission: what a joke, he'd often thought — what purpose could existence have in store for him now? One drunken night he'd renamed the house

'Casa de la Morte'; he figured it was a more appropriate name for what had been a gift from his wife's parents. Once, it had represented family love and support but what remained had no more love or life left in it than a derelict pier sagging into the sea. Once a place of joy and healing, it was begging now for someone to come along and put it out of its misery.

He sat at his kitchen bench and filled a dirty glass with Scotch. The sunlight on the cab ride home had hurt his eyes, and he was starting to feel a hangover coming on; he took a couple of Excedrin and washed them down with the Scotch. He clutched a picture of his daughter and, as the tablets took effect, he mumbled the name Mary. His eyes stared off into space. His mind reached back to a life that, though it was only five years ago, seemed so alien to him now he struggled to believe it had ever been his . . .

***

Malone was with his fifteen-year-old daughter at this same kitchen bench. His wife was making breakfast pancakes and he was reading the morning paper. He was wearing his clerical collar. The sweet smell of frying batter combined with that of freshly-brewed coffee to fill the room.

'Daddy, what does the Lord think about presents?'

He looked up. 'Is that giving or receiving?' he asked.

'Receiving of course, silly!'

Putting on his best sermonising voice, he replied: 'Well, my child, the lord of this house — who as you know is your mother — has presented you with scrumptious pancakes that I think are very good to receive. But the trouble with some gifts is they overstay their welcome.'

He grabbed his love handles and they all laughed.

The laughter faded and the image was replaced by one in which he and his wife were seated, holding hands, teary-eyed in front of the

TV cameras pleading for the safe return of their daughter Mary. The discussion was about the last place she'd been seen, and a beige van marked About Plumbing that had been spotted in the area.

Malone's mind began to race, flashes of his quest to find his daughter rushing in and out of his head. He's before the altar of his church, on his knees, praying for her safe return. He's standing at the church lectern, pleading with the congregation to pray for Mary's safety.

Placing posters, with Mary's photo and a phone number to call, in shop windows and on power poles, in fact anywhere there's a space to put them. Driving around the streets, trawling the red-light areas and the seedy underbelly of central Los Angeles. Spending endless, fruitless hours at the police station reception desk.

The memory flashes began to slow, to linger at specific low points.

The anguish of the time he went to the morgue to identify a girl fitting

Mary's description. Standing outside the room, hoping in a way it would be her, that the uncertainty would end. Sobbing with relief and frustration when it wasn't.

Then, unbearably, the loss of his wife a year later. He saw again the cold steel door opening, the tray being slid out and the green sheet pulled back — the sight of her, beaten and barely recognizable. Even now, the memory sent a shiver down his spine. After that, the praying had stopped and the hating had started, followed by the drinking.

As his mind came back to the present, his eyes focused on his daughter's picture again; the tears rolled slowly from his eyes. He took another shot of whiskey and moved into the living room. It was a mess: there were beer cans, clothes, crumpled snack wrappers, and empty pizza boxes everywhere.

His recliner chair had pride of place in front of the television. He'd slept in that chair so many nights the outline of his body was imprinted there. Locating the remote under a discarded sweatshirt, he flicked on the TV and clicked through the cable channels until he found one showing the news.

A robbery in a downtown gas station was being reported. Two men in ski masks had jumped the counter in broad daylight. One of them had forced the attendant to the ground while the other emptied the cash register and the cigarettes into a bag. Before he left, the man who'd been standing over the employee had produced a hammer and shattered the man's hand, yelling something about making sure he wasn't going to call the cops.

This was followed by the story of a house fire in a suburb on the outskirts of Watts. The fire department suspected arson. As the reporter interviewed a fireman at the scene, people behind him were picking through the charred remains of the house. The next story, a car chase on the freeway, had front-row helicopter coverage. It was like

Grand Theft Auto. The stolen red Lincoln zigzagged through traffic, now and then coming close to hitting other vehicles but fortunately the freeway was quiet. The chase ended in the usual fashion — tyre spikes, sparks, loss of control and a brief pursuit on foot. Malone was beginning to remember why he never used to watch the news when the image of the missing Mary appeared behind the presenter. He turned up the volume.

The presenter introduced the story before crossing to the field reporter, who gave an account of the abduction in a more detailed and visual fashion. Then it was back to the studio and an interview with Mary Salinas' parents filmed earlier. Their pleas for the safe return of their daughter were so heart-rending, so familiar, Malone almost had to turn away, but the sketch of the About Plumbing van demanded his attention. Finally the picture of the abducted girl, her name superimposed, filled the screen.

The presenter concluded, 'If you have any information regarding the disappearance of Mary Salinas, please call the following number.'

The 1-800 number replaced Mary's name, and Malone grabbed a pen from the cabinet next to the television and wrote it on his hand.

An expert on abductions was introduced to the viewers. Journalists and TV stations just have to go that one step further for points in the ratings wars, Malone thought.

A middle-aged man — shabbily dressed, an absent-minded professor type — launched into the appalling statistics. 'In America, NISMART estimates there are between three thousand, six hundred and four thousand, two hundred legally defined, non-family abductions of children a year, that's almost five thousand missing and abducted kids each year,' he told the presenter.

The journalist feigned surprise at the numbers.

'Two to three hundred a year are stereotypical kidnappings or long-term abductions, and unfortunately, some of these children are never returned,' the expert added.

The interview continued but Malone had heard enough. What the hell is an expert on abductions anyway? he asked himself as he flicked off the TV and slumped back into his chair. He needed to think, and he needed another drink, but he was painfully aware the two didn't mix. The bottle of Scotch called to him from the kitchen bench, but as he heaved himself out of the chair, the photo of his daughter fell from the arm to land face-up on the ground.

The message was clear. He knew what he had to do.