City of Fortune: How Venice Won and Lost a Naval Empire (3 page)

Read City of Fortune: How Venice Won and Lost a Naval Empire Online

Authors: Roger Crowley

Tags: #History, #Medieval, #Europe, #General

Since by the Grace of God our city has grown and increased by the labours of merchants creating traffic and profits for us in diverse parts of the world by land and sea and this is our life and that of our sons, because we cannot live otherwise and know not how except by trade, therefore we must be vigilant in all our thoughts and endeavours, as our predecessors were, to make provision in every way lest so much wealth and treasure should disappear.

Its gloomy conclusion echoes a manic-depressive streak in the Venetian soul. The city’s prosperity rested on nothing tangible – no land holdings, no natural resources, no agricultural production or large population. There was literally no solid ground underfoot. Physical survival depended on a fragile ecological balance. Venice was perhaps the first virtual economy, whose vitality baffled outsiders. It harvested nothing but barren gold and lived in perpetual fear that if its trade routes were severed, the whole magnificent edifice might simply collapse.

There is a moment when the departing vessels shrink to vanishing point, and the watchers on the quay turn back to normal life.

Sailors resume their tasks; stevedores heft bales and roll barrels; gondoliers paddle on; priests hurry to the next service; black-robed senators return to the weighty cares of state; the cutpurse makes off with his takings. And the ships surge out into the Adriatic.

Petrarch watched until he could see no more. ‘When my eyes could no longer follow the ships through the darkness, I picked up my pen again, shaken and deeply moved.’

It had been arrival however, rather than departure, which launched the Stato da Mar. A hundred and sixty years earlier, in Lent 1201, six French knights were rowed across the lagoon to Venice. They had come about a crusade.

PART I

OPPORTUNITY: MERCHANT CRUSADERS

1000–1204

Lords of Dalmatia

1000–1198

The Adriatic Sea is the liquid reflection of Italy, a tapering channel some 480 miles long and a hundred wide, pinched tighter at its southern point where it flows into the Ionian past the island of Corfu. At its most northern point, in the enormous curved bay called the Gulf of Venice, the water is a curious blue-green. Here the River Po churns out tons of alluvial material from the distant Alps, which settle to form haunting stretches of lagoon and marsh. So great is the volume of these glacial deposits that the Po Delta is advancing fifteen feet a year and the ancient port of Adria, after which the sea is named, now lies fourteen miles inland.

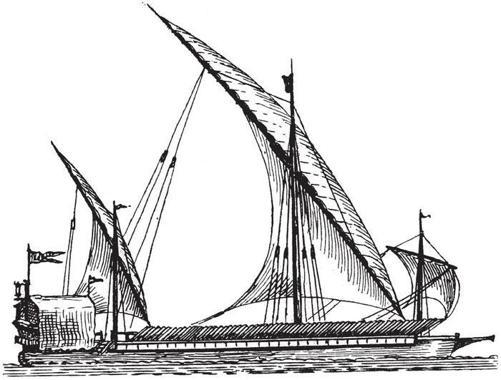

Geology has made its two coasts quite distinct. The western, Italian shore is a curved, low-lying beach, which provides poor harbours but ideal landing spots for would-be invaders. Sail due east and your vessel will snub against limestone. The shores of Dalmatia and Albania are a four-hundred-mile stretch as the crow flies, but so deeply crenellated with sheltering coves, indents, offshore islands, reefs and shoals that they comprise two thousand miles of intricate coast. Here are the sea’s natural anchorages, which may shelter a whole fleet or conceal an ambush. Behind, sometimes stepped back by coastal plain, sometimes hard down on the sea, stand the abrupt white limestone mountains that barricade the sea from the upland Balkans. The Adriatic is the frontier between two worlds.

For thousands of years – from the early Bronze Age until well after the Portuguese rounded Africa – this fault line was a

marine highway linking central Europe with the eastern Mediterranean, and a portal for world trade. Ships passed up and down the sheltering Dalmatian shore with the goods of Arabia, Germany, Italy, the Black Sea, India and the furthest East. Over the centuries they carried Baltic amber to the burial chamber of Tutankhamun; blue faience beads from Mycenae to Stonehenge; Cornish tin to the smelters of the Levant; the spices of Malacca to the courts of France; Cotswold wool to the merchants of Cairo. Timber, slaves, cotton, copper, weapons, seeds, stories, inventions and ideas sailed up and down these coasts. ‘It is astonishing’, wrote a thirteenth-century Arab traveller about the cities of the Rhine, ‘that although this place is in the far west, there are spices there which are to be found only in the Far East – pepper, ginger, cloves, spikenard, costus and galanga, all in enormous quantities.’ They came up the Adriatic. This was the point where hundreds of arterial routes converged. From Britain and the North Sea, down the River Rhine, along beaten tracks through the Teutonic forests, across Alpine passes, mule trains threaded their way to the top of the gulf, where the merchandise of the East also landed. Here goods were transshipped and ports flourished. First Greek Adria, then Roman Aquileia, finally Venice. In the Adriatic site is everything: Adria silted up; Aquileia, on the coastal plain, was flattened by Attila the Hun in 452; Venice prospered in the aftermath because it was unreachable. Its smattering of low-lying muddy islets set in a malarial lagoon was separated from the mainland by a few precious miles of shallow water. This unpromising place would become the entrepôt and interpreter of worlds, the Adriatic its passport.

*

From the start the Venetians were different. The first, rather idyllic snapshot we have of them, from the Byzantine legate Cassiodorus in 523, suggests a unique way of life, independent and democratic:

You possess many vessels … [and] … you live like seabirds, with your homes dispersed … across the surface of the water. The solidity of the earth on which they rest is secured only by osier and wattle; yet you do not hesitate to oppose so frail a bulwark to the wildness of the sea. Your people have one great wealth – the fish which suffices for them all. Among you there is no difference between rich and poor; your food is the same, your houses are alike. Envy, which rules the rest of the world, is unknown to you. All your energies are spent on your salt-fields; in them indeed lies your prosperity, and your power to purchase those things which you have not. For though there may be men who have little need of gold, yet none live who desire not salt.

The Venetians were already carriers and suppliers of other men’s needs. Theirs was a city grown hydroponically, conjured out of marsh, existing perilously on oak palings sunk in mud. It was fragile to the sea’s whim, impermanent. Beyond the mullet and eels of the lagoon, and its saltpans, it produced nothing – no wheat, no timber, little meat. It was terribly vulnerable to famine; its sole skills were navigation and the carrying of goods. The quality of its ships was critical.

Before Venice became the wonder of the world, it was a curiosity; its social structure enigmatic and its strategies distrusted. Without land there could be no feudal system, no clear division between knight and serf. Without agriculture, money was its barter. Their nobles would be merchant princes who could command a fleet and calculate profit to the nearest

grosso

. The difficulties of life bound all its people together in an act of patriotic solidarity that required self-discipline and a measure of equality – like the crew of a ship all subject to the perils of the deep.

Geographical position, livelihood, political institutions and religious affiliations marked Venice out. It lived between two worlds: the land and the sea, the east and the west, yet belonging to neither. It grew up a subject of the Greek-speaking emperors in Constantinople and drew its art, its ceremonial and its trade from the Byzantine world. Yet the Venetians were also Latin Catholics, nominal subjects to the pope, Byzantium’s anti-Christ. Between

such opposing forces they struggled to maintain a particular freedom. The Venetians repeatedly defied the pope, who responded by excommunicating the whole city. They resisted tyrannous solutions to government and constructed for themselves a republic, led by a doge, whom they shackled with so many restraints that he could receive no gift from foreigners more substantial than a pot of herbs. They were intolerant of over-ambitious nobles and defeated admirals, whom they exiled or executed, and devised a voting system to check corruption as labyrinthine as the shifting channels of their lagoon.

The tenor of their relations with the wider world was set early. The city wished to trade wherever profit was to be made without favour or fear. This was their rationale and their creed and they pleaded it as a special case. It earned them widespread distrust. ‘They said many things to excuse themselves … which I do not recollect,’ spat a fourteenth-century churchman after watching the Republic wriggle free of yet another treaty (though he could undoubtedly remember the details painfully well), ‘excepting that they are a quintessence and will belong neither to the Church nor to the emperor, nor to the sea nor to the land.’ They were in trouble with both Byzantine emperors and popes as early as the ninth century for selling war materials to Muslim Egypt, and whilst purportedly complying with a trade ban with Islam around 828, they managed to spirit away the body of St Mark from Alexandria under the noses of Muslim customs officials, hidden in a barrel of pork. Their standard let-out was commercial necessity: ‘because we cannot live otherwise and know not how except by trade’. Alone in all the world, Venice was organised for economic ends.

By the tenth century they were selling oriental goods of extraordinary rarity at the important fairs at Pavia on the River Po: Russian ermine, purple cloth from Syria, silk from Constantinople. One monkish chronicler had seen the emperor Charlemagne looking drab beside his retinue in oriental cloth bought there from Venetian merchants. (Particularly singled out for clerical

tut-tutting was a multicoloured fabric interwoven with the figures of birds – evidently an item of outrageous foreign luxury.) To the Muslims they traded back timber and slaves, literally Slavs until that people became Christians. Venice was by now well placed at the head of the Adriatic to become the pivot of trade, and on the round turning of the millennium, Ascension Day in the year 1000, Doge Pietro Orseolo II, a man who ‘excelled almost all the ancient doges in knowledge of mankind’, set sail on an expedition that would launch the Republic’s ascent to wealth, power and maritime glory.

On the threshold of the new era the city stood finely poised between danger and opportunity. Venice was not yet the compact mirage of dazzling stone that it would later become, though its population was already substantial. No splendid palazzi flanked the great S-bend of the Grand Canal. The city of wonder, flamboyance and sin, of carnival masks and public spectacle lay centuries ahead. Instead low wooden houses, wharves and warehouses fronted the water. Venice comprised less a unity than a succession of separate islets with patches of undrained marsh and open spaces among the parish settlements, where people grew vegetables, kept pigs and cows and tended vines. The Church of St Mark, a plain predecessor of the extraordinary basilica, had recently been badly burned and patched up after political turmoil that left a doge dead in its porch; the square in front of it was beaten earth, divided by a canal and partially given over to orchard. Sea-going vessels that had sailed to Syria and Egypt crowded the commercial heart of the city, the Rivo Alto – the Rialto. Everywhere masts and spars protruded above the buildings.