City of Fortune: How Venice Won and Lost a Naval Empire (35 page)

Read City of Fortune: How Venice Won and Lost a Naval Empire Online

Authors: Roger Crowley

Tags: #History, #Medieval, #Europe, #General

The methods it used to annex new possessions were highly flexible: a mixture of patient diplomacy and short sharp applications of military force. Where the city had obtained an empire by job lot after 1204, these new acquisitions were piecemeal. Ambassadors were despatched to guarantee the safety of a Greek port or a Dalmatian island; an absentee landlord could be tempted to sell up for ready cash; a couple of armed galleys might persuade an embattled Catalan adventurer it was time to go home or swing a factional dispute in a Croatian port; a wavering Venetian heiress might be ‘encouraged’ to marry a suitable Venetian lord or to bestow her inheritance directly on the Republic. If its techniques were patient and variable, the Republic’s underlying policy was frighteningly consistent: to obtain, at the lowest cost, desirable forts, ports and defensive zones for the honour and profit of the city. ‘Our agenda in the maritime parts’, the senate declared in 1441 like a corporation setting out its strategic plan, ‘considers our state and the conservation of our city and commerce.’

Sometimes cities submitted to Venice voluntarily to avoid unwelcome pressures from the Ottomans or Genoese. In each case Venice ran the slide rule of cost–benefit analysis over the application, like merchants eyeing the goods. Did the city have a secure harbour? Good water sources for provisioning ships? An agricultural hinterland? A compliant population? What were its defences like? Did it control a strategic strait? And negatively, what would be the loss if it fell to a hostile power? Cattaro, on the Dalmatian coast, made six requests to submit before the Republic agreed. Patras applied seven times. On each occasion the senators listened gravely and shook their heads. When it came to outright purchase they waited for the stock to fall. Ladislas of Hungary offered his claim to Dalmatia in 1408 for three hundred thousand florins. The following year, with his cities in revolt, Venice sealed it for one hundred thousand. And sometimes the choice

was money or compulsion; the carrot and the stick were applied in equal measure. By patience, bargaining, intimidation and outright force, Venice extended the Stato da Mar.

One by one the red-roofed ports, green islands and miniature cities of Dalmatia and the Albanian coast dropped, almost effortlessly, into its hands: Sebenico and Brazza, Trau and Spalato, the islands of Lesina and Curzola, famous for shipbuilding and sailors, ‘as bright and clean as a beautiful jewel’. The key to the whole system was Zara, over which Venice had struggled to maintain its dominance for four hundred years. Now it submitted to Venice by free will, with cries of ‘Long live St Mark!’ To be quite certain, its troublesome noble families were moved to Venice, then offered positions in other cities along the coast. Once again the doge could style himself lord of Dalmatia. Only Ragusa, proudly independent, escaped permanently the embrace of St Mark.

The value of this coast was inestimable. Venetian galley fleets could thread their way up the sheltered channels of its coast; protected by its chain of islands from the Adriatic’s unpredictable winds – the sirocco, the

bora

and the

maestrale

– they could put in at its secure harbours. The Republic’s ships would be built from Dalmatian pine and rowed or sailed by Dalmatian crews. Manpower was as important as wood, and the maritime skills of the eastern shore of the Adriatic would be at the disposal of Venice for as long as the Republic lasted.

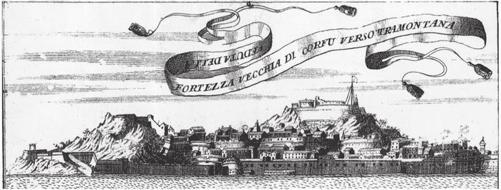

If Zara was important, the acquisition of Corfu was more so. They bought the island from the king of Naples in 1386 for thirty thousand ducats and with the ready acceptance of its populace, ‘considering the tempest of the times and the instability of human affairs’. Corfu was the missing link in a chain of bases. The island – which Villehardouin had found ‘very rich and plenteous’ when the crusaders stopped there in 1203 – occupied an emotional place in the city’s history. Here the Venetians had lost thousands of men in sea battles against the Normans in the eleventh century; they were gifted it in 1204, held it briefly, then lost it again. Its position, guarding the mouth of the Adriatic, also

provided critical oversight of the east–west traffic between Italy and Greece. Across the straits, Venice acquired the Albanian port of Durazzo, rich in running water and green forests, and Butrinto just ten miles away. This triangle of bases controlled the Albanian coast and the seaway to Venice.

The fortress of Corfu

Corfu itself, verdant, mountainous, watered by the winter rains, became the command centre of Venice’s naval system and its choice posting. They called it ‘Our Door’ and stationed a permanent galley fleet in its secure port under the captain of the Gulf; in times of danger his authority would be trumped by the all-powerful captain of the sea, whose arrival was announced with belligerent banners and the blare of trumpets. All passing Venetian ships were mandated to make a four-hour stopover at Corfu to exchange news. They came gladly, seeing the outline of the great island floating up out of the calm sea, like a first apprehension of Venice itself. Corfu provided fresh water and the delights of port. The prostitutes of the town were renowned, both for their favours and the ‘French disease’; and sailors on the homeward run, being pious as well as frail, also stopped further up the coast at the shrine of Our Lady of Kassiopi to give thanks for the voyage.

The Ionian islands south from Corfu were added in this new wave of empire: verdant Santa Maura, craggy Kefallonia, and ‘Zante,

fior di Levante

’ (Flower of the Levant) in the Italian rhyme. Lepanto, a strategic port tucked into the Gulf of Corinth and potentially attractive to the Ottomans, was taken by despatching

the captain of the Gulf with five galleys and emphatic orders to storm or buy the place. Faced with the choice of decapitation or a safe conduct and 1,500 ducats a year, its Albanian lord went quietly.

The gold rush of new acquisitions stretched round the entire coast of Greece. Zonchio, a well-protected harbour close to Modon, was bought in 1414; Naplion and Argos in the Gulf of Argos came by bribery; Salonica begged for protection from the Turks in 1423. Shrewd in their moves and cognisant of their manpower shortages, untempted by feudal ambition and landed titles in a landscape that yielded so little, the senate refused the submission of inland Attica. What mattered and only mattered was the sea.

Further south, the barren islands of the Cyclades, offered to Venetian privateers after 1204, had become an increasing problem. The Republic had repeated difficulties with their overlords, by turns treacherous, tyrannical, even mad. Turkish, Genoese and Catalan pirates also plundered the islands, abducted their populations and rendered the sea lanes unsafe. As early as 1326, a chronicler wrote that ‘the Turks specially infest these islands … and if help is not forthcoming they will be lost’. The Florentine priest Buondelmonti spent four years in the Aegean in the early 1400s and travelled ‘in fear and great anxiety’. He found the islands wretched beyond belief. Naxos and Siphnos lacked any sizeable male population; Seriphos, he declared, offered ‘nothing but calamity’, where the people ‘lived like brutes’. On Ios the whole population retreated into the castle each night for fear of raiders. The people of Tinos tried to abandon their island altogether. The Aegean looked to the Republic for protection, ‘seeing that no lordship under heaven is so just and good as that of Venice’. The Republic started to reabsorb these islands, but as ever its approach was fiercely pragmatic.

*

The empire that Venice acquired in this second wave of colonial expansion was held together by muscular sea power. To its triangle of priceless keystones – Modon–Coron, Crete and Negroponte – was now added Corfu. But beyond, the Stato da Mar was a shifting,

supple matrix of interchanging locations, flexible as a steel net. The Venetians lived permanently with impermanence and many of their possessions came and went, like the moods of the sea. At one time or another they occupied a hundred sites in continental Greece; most of the Aegean islands passed through their hands. Some slipped from their grasp only to be regathered. Others were quite ephemeral. They held the rock of Monemvasia, shaped like a miniature Gibraltar, on and off for over a century and they were in and out of Athens. They had a foothold there in the 1390s, when they watched Spanish adventurers stripping the silver plates from the Parthenon doors, then ruled it themselves for six years. Fifty years later they were offered it again, but by then it was too late.

Nowhere exemplified reversals of colonial fortune as sharply as Tana, on the northern shores of the Black Sea. After Venice was ousted by the Mongols in 1348, a merchant settlement was restored in 1350 and maintained for half a century. But Tana was so far away that news was slow to reach the centre. The galley fleets made their annual visit then vanished again over the sea’s rim. Silence gripped the outpost for long months. When Andrea Giustinian was sent to Tana in 1396, he was staggered to discover nothing there – no people, no standing buildings – just the charred remains of habitations and the eerie crying of birds over the River Don. The whole settlement had gone down in fire and blood before an assault by Tamburlaine, the Mongol warlord, the previous year. In 1397 Giustinian appealed to the local Tatar lords for permission to build a new, fortified settlement. Venice simply started again. Tana was that important.

But in the centre of the eastern Mediterranean, Venice ran an imperial system of incomparable efficiency. Throughout the region, wherever the flag of St Mark was flown, the propaganda symbols of Venetian power – economic, military and cultural – were visible: in the image of the lion, carved into harbour walls and above the dark gateways of forts and blockhouses, growling at would-be enemies, offering peace to friends; in the bright roundels of its gold ducats, on which the doge kneels before the saint himself, whose purity

and credibility undermined all its rivals; in the regular sweep of its war fleets and the spectacle of its merchant convoys; in the sight of its black-clad merchants pricing commodities in the Venetian dialect; in its ceremonies and the celebration of feast days; in its imperial architecture. The Venetians were omnipresent.

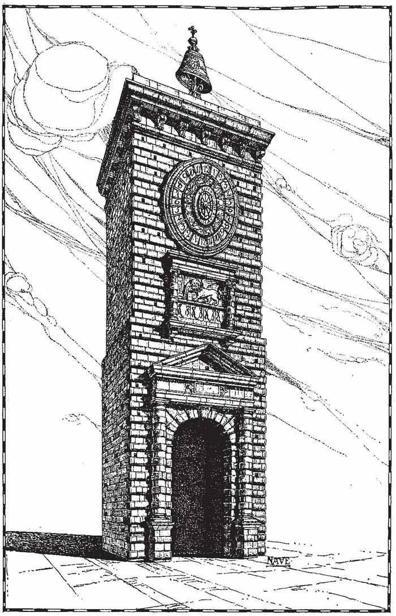

The city exported itself across the sea. Candia was styled

alias civitas Venetiarum apud Levantem

, ‘another city of the Venetians in the Levant’ – a second Venice – and it replicated its buildings and its emblems of power. There was the Piazza San Marco, faced by the Church of St Mark, a clock tower flying the saint’s flag, which like the bells of the campanile in Venice signalled the start and end of the working day, and the ducal palace and the loggia for conducting business and the buying and selling of goods. Two columns stood beside the palace for the execution of criminals, echoing those on the Venetian waterfront, reminding citizens and subjects alike that the writ of exemplary Venetian justice ran in the world. Here the Venetian state was reproduced in miniature: the chamber for weighing wholesale commodities using Venetian weights and measures, the offices dealing with criminal and commercial law, the antechambers and sub-departments of the Cretan administration, similar to those of the doge’s palace. Through half-closed eyes a travelling merchant could believe himself transported to some reflection of Venice, remade in the brilliant air of the Levant, like an image by Carpaccio repainting Venice on the shores of Egypt, or an English church in the Raj. Outsiders remarked on this trick of the light. ‘If a man be in any territory of theirs,’ wrote the Spanish traveller Tafur, ‘although at the ends of the earth, it seems as if he were in Venice itself.’ When he stopped at Curzola, on the Dalmatian coast, he found that even the local inhabitants had fallen under the Venetian sway: ‘The men dress in public like the Venetians and almost all of them know the Italian language.’ Constantinople, Beirut, Acre, Tyre and Negroponte all had a church of St Mark at one time or another.

Imperial monuments: the clock tower at Retimo

Such features made the travelling merchant or the colonial administrator feel that he occupied his own world; they fended

off homesickness and projected Venetian power to their subjects, be they speakers of Greek, Albanian or Serbo-Croat. This was reinforced by the ritual elements of Venetian ceremonial. The formally orchestrated ceremonies so carefully detailed in fifteenth-century paintings were exported to the colonies. The arrival of a new duke of Crete, stepping from his galley to an announcement of trumpets under a red silk umbrella, met at the sea gate by his predecessor and walked in solemn procession up

the main street to the cathedral and the anointment with holy water and incense – these were highly scripted demonstrations of Venetian glory. The stately processions, the banners of St Mark and the patron saints, the oaths of loyalty, submission and service to the Republic by subject peoples, the singing of the Lauds service in praise of the duke on the great feast days of the Christian year – these rituals fused secular and religious power in displays of splendour and awe. The pilgrim Canon Pietro Casola witnessed such ceremonial at a handover of the Cretan administration in 1494, which was ‘so magnificent that I seemed to be in Venice on a great festival’.