City of Fortune: How Venice Won and Lost a Naval Empire (42 page)

Read City of Fortune: How Venice Won and Lost a Naval Empire Online

Authors: Roger Crowley

Tags: #History, #Medieval, #Europe, #General

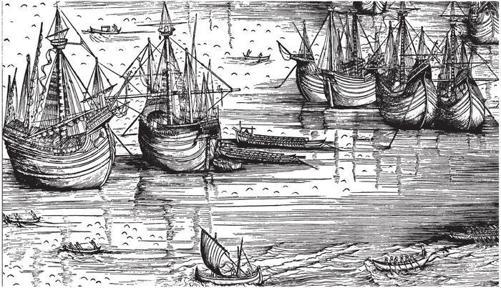

Round ships and galleys in the Basin of St Mark

The arsenal produced not only ships of war but also the state-owned merchant galleys that formed the regular

muda

runs. For Venice, shipping was binary, a deeply understood set of alternatives. There were oared galleys and sailing ships; war galleys and great galleys; private vessels and state-owned ones; armed and disarmed vessels – not so much an opposition between fighting and merchant vessels, because merchant galleys could be used in war, and all ships carried a certain quantity of weapons – more an understanding as to whether a vessel was to sail out with a full complement of men, heavy armour, arquebuses and trained crossbowmen, or not. The state attended closely to their management. A maritime code was first introduced in 1255 and continuously refined. There were laws

about loading, crew sizes, the quantity of arms to be carried, the duties and responsibilities of captains and other sea-going officials, taxes to be paid and the managing of disputes.

Every ship had a specified carrying capacity – calculated by mathematical formula in the fifteenth century – and a load line was marked on its side, a forerunner of the Plimsoll line. Before departure, ships were inspected to ensure that they were legally loaded, with a crew adequate to their size and the requisite quantity of weapons. Such regulations could be minutely fine-tuned according to circumstance; when ships were obliged to carry more arms by the law of 1310, they were permitted to load just one inch deeper; from 1291 hats were ordered to replace hoods as protective military headgear; when it became practice on large sailing ships mechanically to compress lightweight bulky loads, such as cotton, with screws or levers, the dangers of damage both to goods and hull became subject to legislation. Maritime law then distinguished between loading by hand and by screw, with the limits on mechanical loading fixed according to the ship’s age.

The business of the sea was managed as consistently as the Stato da Mar itself – by regulation, continuous oversight and recourse to law. These hallmarks of the Venetian system, widely admired by outsiders for its good order and sense of justice, ran through all its maritime arrangements. They replicated in miniature all the characteristic workings of the whole state and were closely attended to by the doge and ducal council. Sets of elected officials monitored, inspected, organised and fined both the state and the private sectors: they inspected crews, checked cargoes and collected custom and freight dues, rated loading capacities and handled legal disputes between shippers, masters and crew.

State-controlled voyages were organised at the highest level by elected officials of the Great Council, the central governing body of Venice. The

savii

, as they were called, planned the

mude

for the coming year, based on a continuous stream of intelligence about threats of war, the political stability of destinations, the state of markets and food stocks and the level of piracy. Their remit was

wide. They could stipulate fleet sizes, routes, landing stages, durations of stops, freights to be carried and freight rates. Conditions would be most onerous with regard to high-value cargoes – the transportation of cloth, cash, bullion or spices – and the conveying of important state functionaries, ambassadors and foreign dignitaries. No leasing consortium could refuse to load legitimate freight from any merchant. Even after the vessels had been leased, the ships and their crews could be peremptorily requisitioned in the event of war. The state appointed its own official on merchant galleys, the

capitano

, the nautical and military leader of the fleet, tasked with protecting the Republic’s property and the lives of its citizens. Everyone on board down to the lowliest oarsman was contracted to the venture by sworn oath.

*

The regulation, the safety measures, the quality controls in the materials production in the arsenal, the attempts to legislate against human fallibility, fraud, exploitation and greed were founded on long experience of voyaging. The sea was a taskmaster that could turn profit into plunging loss, safety into extreme danger on a shift of the wind. Nothing made the Venetian system shudder more than dramatic cases of failure. In the spring of 1516, the

Magna

, an older merchant galley, was being fitted out for the Alexandria run. From March to July it was in the arsenal undergoing an examination of the hull. There was unanimous agreement that the vessel was dangerous; it needed repairs for which the hiring consortium was reluctant to pay, and they were anxious not to miss the spice fairs. The arsenal authorities finally permitted departure, with the empty assurance that it would be repaired further down the Adriatic at Pola. The

Magna

sailed on past Pola, carrying, amongst other things, a cargo of copper bars that may or may not have overloaded the vessel. It probably had a crew of about two hundred.

On 22 December, 250 miles off Cyprus, the

Magna

hit a storm and started to ship water. As it thrashed in the rolling sea, the copper bars broke loose and tumbled across the hold; at dawn

the following day the vessel broke up into three parts. There was an instant rush for the ship’s boat, which quickly became overloaded. Some managed to scramble aboard, others were forcibly prevented with drawn swords. The late arrivals slipped back into the sea and drowned. There were now eighty-three men crammed onto a raft of death. They contrived a rudder and crude sails from sacks, spars and oars, and tried to sail to Cyprus. For a week they tossed violently day and night on a tempestuous sea ‘with waves as tall as St Mark’s’. They had no food or water. One by one the men started to die of hunger, thirst and cold. They drank their own urine and ate the shirts off their backs; they started to hallucinate: they saw saints carrying bright candles across the sky. Civilisation collapsed. ‘And perhaps’, it was elliptically explained in a letter from Cyprus, ‘some went to alleviate the hunger of others, and they had already resolved to kill the little ship’s clerk, because he was young, fat and juicy, to drink his blood.’ On the eighth day they sighted land but were too weak to choose a safe landing spot. Some drowned in the swell; the rest crawled ashore on their knees. Of the original eighty-three, fifty were still alive. ‘A young Soranzo has survived,’ it was reported, ‘but he is only holding onto life by the skin of his teeth, and the

patrono

, the noble Vicenzo Magno, but he is very sick and likely to die … certain of the other survivors will present the boat as an offering of the True Cross, and some will go on a barefoot pilgrimage to one place, others to another. All have made various vows.’ The writer of the letter drew sober conclusions:

… this is a most wretched event. Sea voyages entail too many grave dangers, and it’s all through greed for money. By what passage I shall come home, I can’t tell you. Again this morning I had mass said to the Holy Spirit and Our Lady, because my fear of travelling in old galleys is so great, having seen the wreck of the one bound for Alexandria..

Despite de’ Barbari’s Neptune, Venetians were always ambivalent about the sea; it was both the cornerstone of their existence and their fate. They believed they owned it all the way to

Crete and Constantinople, but it was also dangerous, infinite and unappeased – ‘a zone that it is boundless and horrifying to behold’, wrote Cristoforo da Canal, an experienced captain of the sixteenth century. If the Senza was a claim to possession, its subtext was fear. Storm, shipwreck, piracy and war remained cardinal facts. The galley life was particularly hard and increasingly unwelcome as the centuries went on. The sense of shared purpose had begun to fragment. The status of the

galeotti

– the oarsmen sitting at the narrow benches in all weathers – declined steadily with a growing specialism of roles on ships and an aggregation of wealth and power among the noble class. They existed on a diet of wine, cheese, coarse bread, ship’s biscuit and vegetable soup. With the nautical revolution, the development of winter sailings worsened their lot – Pisani’s sailors, frostbitten and underfed, died of cold. Wages were pitiful; they were made up by the opportunity to trade on their own initiative on the merchant galleys: each man was permitted to carry on board a sack or chest.

In the war galleys, the captains who commanded respect, such as Vettor Pisani and the maverick Benedetto Pesaro a century later, understood what a man at the oars needed to live. A tolerable diet, protection from the worst of winter sailings and the chance to seize booty would win enduring loyalty from the men of the bench. For commanders who would share their food and the perils of battle they would go through hell. It was the galley crews who hammered on the door of the council chamber to free Pisani and who demanded his coffin; for more standoffish aristocrats they occasionally went on strike. They wanted comradeship, identity and a shared destiny. Their patriotism to St Mark was unbounded; when Venetian sea power faced its ultimate test in 1499 it would not be the men of the bench who failed.

By the late fifteenth century, they formed a veritable underclass; many on the merchant galleys were debt slaves to the captains, though rarely chained, and as the Black Death thinned the Venetian population they were increasingly drawn from the colonies. The Dalmatian coast and the shores of Greece were a

crucial resource of raw manpower. The German pilgrim Felix Fabri observed their lot closely on the galleys to the Holy Land in 1494:

There are a great many of them, and they are all big men; but their labours are only fit for asses, and they are urged to perform them by shouts, blows and curses. I have never seen beasts of burden so cruelly beaten as they are. They are frequently forced to let their tunics and shirts hang from their girdles, and work with bare backs, arms and shoulders, that they may be reached with whips and scourges. These galley slaves are for the most part the bought slaves of the captain, or else they are men of low station, or prisoners, or men who have run away. Whenever there is any fear of their making their escape, they are secured to their benches by chains. They are so accustomed to their misery that they work feebly and to no purpose unless someone stands over them and curses them. They are fed most wretchedly, and always sleep on the boards of their rowing benches, and both by day and night they are always in the open air ready for work, and when there is a storm they stand in the midst of the waves. When they are not at work they sit and play at cards and dice for gold and silver, with execrable oaths and blasphemies …

The good friar was most vexed by the swearing. Protection from his crew was one of the contractual obligations that the captain of a merchant galley had to his pilgrim passengers.

Insecurity was built into the seafaring life; any encounter with an unrecognised ship might cause alarm. In situations of uncertainty, galleys would enter a foreign port backwards, crossbowmen covering the shore with cranked bows, the oarsmen ready to pull out at a blast of the whistle. With the decline of the Byzantine Empire, piracy, always endemic to the Mediterranean, had a ratcheting effect on the maritime system. After 1300, freebooting Catalans, ousted Genoese factions, Greeks, Sicilians, Angevins – and increasingly Turks from the coasts of Asia Minor – turned the sea into a free-for-all. In 1301, all vessels were ordered to augment their armed defences; in 1310, state galleys had to enrol twenty per cent of their crew as bowmen. The crew were all expected to

fight and were issued with weapons; laws required the provision of specified quantities of plate armour. The

muda

system, where merchant galleys travelled in convoy, was introduced to ensure a level of mutual defence. Their sizeable crews – about two hundred men – were a deterrent to all but a squadron of Genoese war galleys. It was the lone private sailing ship that was more likely to be picked off by pirates lurking in a passing cove. For Venice, piracy was the most detested crime, an affront to business and the rule of law. The Republic preferred its maritime violence organised at state level. The registers minute thousands of instances of robbery or dubious confiscation of cargoes under pretext, followed by demands for restitution from other states held responsible for the actions of its citizens, but at sea it was frequently the survival of the fittest.

Cleansing the waters of pirates was the duty of both war fleets and merchant galleys. The contests were bloody and punishments exemplary. Captured pirates would be chopped up on their own decks or hanged from their masts, their ships burned. Retribution was particularly ferocious against Christian subjects of the Stato da Mar, but the fate of a detested Turkish pirate in 1501 probably made even the tough-minded Venetians pause. The captain-general of the sea, Benedetto Pesaro, wrote to explain his fate.

The Turkish pirate, Erichi, chanced to land on Milos, returning from Barbary. His ship ran aground on the island during a storm. There were 132 Turks on board. He was captured alive with thirty-two of them. The others drowned or were killed by the people of the island, but we kept hold of him. On 9 December we roasted Erichi alive on a long oar. He lived for three hours in this agony. In this way he ended his life. Also we impaled the pilot, mate and a

galeotto

from Corfu, who betrayed his faith. We shot another with arrows and then drowned him … Erichi the pirate caused considerable damage to our shipping during peacetime.