City of Light

Authors: Lauren Belfer

Tags: #Fiction, #Mystery, #Romance, #Contemporary, #Historical, #adult

Praise for

CITY OF LIGHT

“BEAUTIFULLY WRITTEN, a book that elegantly combines history with page-turning suspense….

City of Light

stands comparisons with the smart historical fiction of writers like E. L. Doctorow and T. C. Boyle. And its mystery will grab readers the way A. S. Byatt’s

Possession

or Caleb Carr’s

The Alienist

did.”

—

Milwaukee Journal Sentinel

“An impressive debut.”

—

The New York Times

“A mysterious death, vibrant characters and a riveting plot will keep your eyes glued to the pages.”

—

Glamour

“Gripping.”

—

Los Angeles Times

“Like Niagara Falls itself, it’s breathtaking in its achievement. Belfer handles it all—large cast, big themes—with uncommon assurance. Her story does not meander like the Mississippi. It

moves

like the Niagara. The river’s famous falls get the visitors they deserve. This book should have the same.”

—Erik Brady,

USA Today

“[A] LUMINOUS AND RIVETING FIRST NOVEL … In gorgeous, exacting prose, Belfer creates a compelling heroine…. I am grateful for having found such a talented writer as Lauren Belfer.”

—

The Plain Dealer

(Cleveland)

“DELICIOUS MELODRAMA. BELFER SHOWS OFF A MASTERFUL ABILITY TO KEEP PAGES TURNING WITH SHAMELESS STYLE.”

—

San Francisco Chronicle

“REMARKABLY ACCOMPLISHED … EXHAUSTIVELY RESEARCHED, INGENIOUSLY PLOTTED …

City of Light

’s rousing success as a literate page-turner, a moving excursion into the inner sanctum of a brave woman’s heart, and a love letter to Belfer’s hometown are secondary to its rare and valuable evocation of a bygone Buffalo and its era. This panoramic, exquisite rendering of a nation on the cusp of modernity gives us an appreciation of the past that serves us well as we anticipate the approaching millennium.”

—

The Orlando Sentinel

“A REMARKABLE ACHIEVEMENT.”

—

St. Louis Post-Dispatch

“[THIS] NOVEL HAS SOMETHING FOR EVERYBODY—IT’S A THRILLER, IT’S A ROMANCE, IT’S A WELL-RESEARCHED HISTORICAL NOVEL.”

—

The Miami Herald

“CITY OF LIGHT

IS A PLEASURE TO READ—the perfect choice for a long airplane ride, a week on the beach, or a rainy weekend at the lake.”

—

The Sunday Oregonian

“With just the right blend of Victorian and modern cadences, [Belfer] weaves a multilayered mystery, unraveled by an independent-minded, thoroughly engaging heroine.”

—

Elle

“AMBITIOUS, ORIGINAL AND TIMELY … a complicated and imaginative story with many daring subplots and colorful secondary characters.”

—

The Washington Post Book World

“AN AMBITIOUS AND COMPELLING FIRST NOVEL … A SKILLFUL BLEND OF FACT AND FICTION,

City of Light

is a rich, rewarding novel…. [It] concerns itself with murder, with revolution, with friendship, with discrimination—racial, intellectual, and social—but, most of all, the book focuses on power, in a tale narrated in Louisa’s deceptively placid, consciously rational, yet still poetic voice.”

—

The Fort Worth Star-Telegram

“A credibly detailed picture of turn-of-the-century life … compelling descriptions of Niagara Falls … an unusual first novel, and well worth the read.”

—

The San Diego Union-Tribune

“[A] RICHLY EVOCATIVE FIRST NOVEL … signaling the debut of a writer of genuine vision and range … The dialogues are especially convincing, written with the repressed subtlety and indirection of a Henry James novel. And Belfer does a wonderful job of evoking the era, its manners and codes, its sense of the beauty of progress and technology.”

—

San Antonio Express-News

“[An] impressive first novel.

City of Light

may well put Buffalo on the literary map the way William Kennedy’s

Ironweed

did for another upstate city, Albany.”

—

Newsday

“With the assurance of an established writer, Belfer delivers a work of depth and polish—complete with dangerous liaisons, gorgeous descriptions of the Falls and a central character whose voice is irresistible to the last page.”

—

Publishers Weekly

“A REMARKABLE ACCOMPLISHMENT … Those who find

City of Light

will be rewarded by richly drawn historical fiction as sure and inspiring as the Niagara Falls against which Belfer sets her story of romance, power and deception.”

—

The Hartford Courant

“[A] DESERVEDLY ACCLAIMED FIRST NOVEL … [A] THRILL-PACKED DEBUT.”

—

Us

“AMAZING … Imagine E. L. Doctorow’s

Ragtime

as the brother of Caleb Carr’s

The Alienist

married to … A. S. Byatt’s magnificent novel,

Possession

, and you have some idea of the pleasure of Belfer’s first novel. Her story is fascinating. Her achievement, though, is quite beyond that…. Not just an irreplaceable literary contribution to our city, it is, I think, a canny contribution to American literature.”

—

The Buffalo News

“An ambitious, vividly detailed and stirring debut novel offering a panorama of American life at the beginning of the 20th century … Belfer’s portrait of the nation at a hard and ebullient time, while likely to remind some readers of Doctorow’s

Ragtime

, is less chilly and more subtle than that work, and very gripping … a remarkably assured and satisfying first novel.”

—

Kirkus Reviews

“AN EXCELLENT LITERARY AND HISTORICAL THRILLER, well-researched and narrated by a voice of heartbreaking gravity … big and bold.”

—

The Times

(London)

“SWIFT AND GRACEFUL READING … EXCEPTIONALLY WELL CRAFTED.”

—

Library Journal

“The historical elements in

City of Light

work so well because they are presented through credible characters … an engaging work.”

—

Houston Chronicle

For my parents

I

am lucky: I know what people say about me

.

To some I am a bluestocking, a woman too intellectual to find a husband. To others an old maid, although I do not consider myself old and I am no maiden. To still others, I’ve flirted with Boston marriages: I’ve lived with other women, they say, but I never have—not that way, at least; not the way they are implying. Nonetheless there is a certain benefit in being so considered: Wives do not fear their husbands spending time with me, and overenergetic husbands look elsewhere for their dalliances

.

Yes, people misjudge me. They hear the title “headmistress” and assume a certain sort of woman. A woman without passion or experience. They never guess the truth of my life, and their assumptions lend me a freedom they would never credit. Thus has society given me room to maneuver. In secret, granted. But self-knowledge is, as the ancient Greeks might say, the only knowledge worth having

.

And when I rise in the gray shadows of dawn, a cooling breeze coming through the open window, my hair flowing around me, my nightdress loose, my body warm beneath it, I gaze in the mirror and see myself for what I am: a woman of feeling, desire, even beauty. Then step by step I create the person I must be: The warm, free body becomes corseted and covered with a high-collared navy-blue dress; the flowing hair is twisted into a tight bun; sturdy shoes take the place of bare feet. What do I hide? My joy, my memories, my dreams of those I’ve loved and what they might have been, my mind harkening back to the time when I knew them still

.

Louisa Barrett

,

1909

PART I

The city of Buffalo has, by the census of 1900, a population of 352,387, standing eighth among the cities of the United States. It leads the world in its commerce in flour, wheat, coal, fresh fish, and sheep, and stands second only to Chicago in lumber. In cattle and in hogs, only Chicago and Kansas City exceed it…. Its railroad yard facilities are the greatest in the world, and are being increased rapidly…. In marine commerce, although the season is limited to six months, Buffalo is exceeded in tonnage only by London, Liverpool, Hamburg, New York, and Chicago

.

Better still, it is a city of homes. Strangers view with delight its shaded streets and spacious lawns…

.

The Niagara Book

,

William Dean Howells,

Mark Twain, and others, 1901

The whole world will pay her tribute

.

“The City of Buffalo,”

Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, 1885

CHAPTER I

O

n the first Monday in March 1901, in the early evening when the sound of sleigh bells filled the air, a student unexpectedly knocked at my door. I was accustomed to receiving visitors on Mondays before dinner, when my drawing room was transformed into a salon. Bankers and industrialists would stop by my comfortable stone house attached to the Macaulay School, knowing they would find professors and artists, editors and architects.

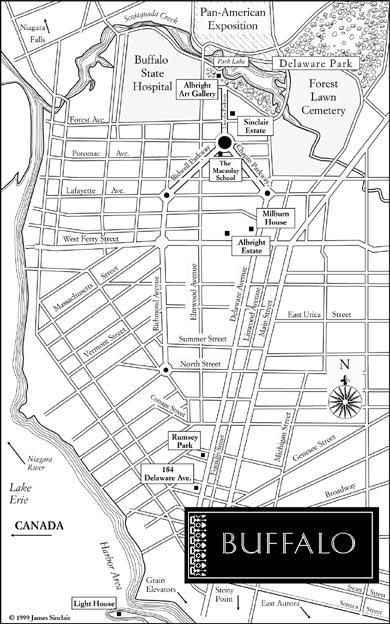

In those days, Buffalo was flush in an era of extraordinary economic prosperity and civic optimism. The city had become the most important inland port in America because of its pivotal location at the eastern end of the Great Lakes. Indeed, at the turn of our century, Buffalo had taken its place among the great cities of the United States. Many of the visitors to my salon were from New York City or Chicago, men who came to Buffalo at the behest of our public-spirited business leaders to offer their best work to the city. These included architects Louis Sullivan and Stanford White; sculptors Augustus Saint-Gaudens and Daniel Chester French. Years ago I met architect Daniel Burnham and he invited himself for sherry with a man whose name I now forget, and came again on his next visit to Buffalo. Soon they all came, presenting their cards with a note: “At the suggestion of our mutual friend …” Then the local people of distinction, with such family names as Rumsey, Albright, and Scatcherd, sensing an opportunity, came calling too.

They could do this only because I was considered unmarriageable. Because I was a kind of “wise virgin”—an Athena, if you will—these men granted me my freedom and I granted them theirs. Of course there were women at my salon—doctors, architects, artists. Those who had husbands came with them; those who did not came alone, or with the other women who were their life companions.

I liked to think that my Monday evening salon was the only place in the city where men and women could mingle as equals. The married and marriageable women of the upper reaches of the town were hidden away, given little room for interests beyond clothes, children, entertaining, and a bit of work among the poor. They led a limited life, which filled me with sadness and which I tried at Macaulay to change. I educated the young women placed in my care—the daughters of power and wealth—to expect more. I liked to think that I’d trained a generation of subversives who took up their expected positions in society and then, day by day, bit by bit, fostered a revolution.

In the past two years, the stream of visitors to my salon had become ever more fascinating and their concerns ever more urgent as they planned the design and construction of a world’s fair called the Pan-American Exposition. Yes, Buffalo was to be an exposition city now, in the tradition of Philadelphia and Chicago. The Pan-American would celebrate the commercial links between North and South America as well as America’s technological breakthroughs, particularly in the area of electricity, which was being developed at nearby Niagara Falls. Most important, the Pan-American’s very existence symbolized and confirmed Buffalo’s new, vital place in the nation.

The exposition site was less than a mile from my home, and over eight million people from around the country and the world were expected to visit the fair during the coming summer. Debates about lighting, coloring, and schematic statuary took place before my fire, the gentlemen tapping their pipes against the mantel. Sometimes they called my gatherings a “saloon” instead of a salon, as if they were visiting the Wild West and I were Annie Oakley. I tried not to show them how much their teasing pleased me.

But on this particular Monday evening in March, I sent my visitors away by seven. There was a wet snow falling and a chill dampness in the air that made me want to be alone in front of the fire. My guests grumbled halfheartedly, though some of them were privately grateful, no doubt, to return home; here on the shores of Lake Erie we respected the icy storms of early spring. And although they might not admit it, more than a few of my out-of-town visitors probably yearned to leave business behind and move on to a relaxing game of whist in the mahogany-paneled confines of the all-male Buffalo Club. Even so, exposition president John Milburn was chagrined to be forced to cut off his conversation with chief architect John Carrère. “You’re sending us out to talk in the snow?” he queried in the hallway.

“Absolutely,” I replied. “You should walk the exposition grounds in the snow and evaluate your work right there—much better altogether.” The men laughed as they gathered their coats and made their way out the door.

After they were gone, I sat in my rocking chair, resting my head, luxuriating in the evening. Then in the quiet, I heard my favorite sound: sleigh bells jingling on harnesses as the horses trotted down Bidwell Parkway, sleigh gliders swishing through the snow. At this hour, bejeweled couples cloaked in fur against the cold were on their way to dinner parties; snowstorms were never permitted to interfere with the social swirl. Closing my eyes, I conjured a scene in my mind: a dining room with French doors and a coffered ceiling, a long table laid for twelve, freshly polished silver, candlelight throwing rainbows through the crystal. I was forever apart from that life, observing it, never living it. Nonetheless I pictured myself reclining on a sleigh, the harness bells dancing, a bison skin pulled around me for warmth as snowflakes touched my face and I was carried to dinner at the estate of John J. Albright or Dexter P. Rumsey.

A knock at the front door intruded on my thoughts. Not wanting to be rude to latecomers, I rose and went into the hall. My Polish housekeeper, Katarzyna, had already opened the door, but she had not welcomed the visitor.

“People gone now. Visiting time finished,” she said with a cut of her hand, as if to shoo the caller away.

The reason for her behavior was clear: One of my students was at the door, peering around Katarzyna to find me. Millicent Talbert, age thirteen, mature-looking for her years but possessed of an innocence and earnestness which at school made her the one who always missed the jokes.

“Miss Barrett?”

There was a hint of the Middle West in her speech. Millicent was an orphan who had come to Buffalo from Ohio to live with her aunt and uncle, who had adopted her. In the unlit doorway, Millicent was a shadow against the white of the evening.

“I’m sorry, Miss Barrett, I don’t want to bother you, but—” She paused, glancing at Katarzyna. “May I speak with you? Just you, I mean. I watched from the corner and waited until everyone left, really I did, Miss Barrett, I didn’t want to disturb you. I didn’t want to cause trouble.”

Millicent Talbert never stopped apologizing. For she appeared agonizingly aware at every moment that she was what the people of Buffalo called “colored.” She seemed to fear that each time she stepped out of her own neighborhood her color was the only thing anyone noticed about her. And she was right. Among Macaulay’s nearly two hundred fifty students, she was the first, and only, colored girl. Many parents assumed she was a gifted scholarship girl, but although she was gifted, she did not attend on scholarship. Her family paid full tuition and was also generous with donations. There had been some protest when I accepted her application, from parents worried about their daughters sitting next to a colored person in class, sharing a cloakroom with her, dining side by side at noontime. But Millicent was from a good family—meaning a

rich

family in society parlance—and the board of trustees had backed me more strongly than I expected. As it turned out, the girls themselves welcomed Millicent, I’m happy to say, regarding her as something of an exotic in their midst and befriending her with ease.

“I don’t mind talking at the door, Miss Barrett, if that’s better for you.”

We might have been completely alone, the three of us lost in a wilderness of snow.

“Come in, Millicent.” I reached out to her, bringing her inside. Her hands felt frozen, and I rubbed them between mine. “How long have you been waiting?” Instead of answering, she leaned into me for a hug of warmth. The snow on her hat touched my cheek.

“Katarzyna, please bring a pot of cocoa to my study for Miss Talbert. And hang this up, will you?” I said, as I helped Millicent take off her wet coat.

Katarzyna stepped back, her face revealing a combination of apprehension and disdain.

Giving Katarzyna a severe look, I hung up the coat myself and led Millicent to the study. I settled her opposite me before the fire.

“So, my dear, what prompts you to wait out in the snow instead of coming to my office in the morning?” I made my voice easygoing, knowing how Millicent’s serious nature sometimes led her to fixate on things. I was prepared to be gentle with her: She was interested in the sciences, and I cherished a dream that she would become a scientific researcher. Her patient, exacting nature would be suited to such a profession.

“I didn’t know what to think, Miss Barrett. It was”—she paused—“strange.”

“What was strange?”

“We were walking home. I mean, I was walking

her

home.”

Dealing with young persons can be frustrating. “I think you’d better start at the beginning.”

“Oh.” She glanced at me in surprise. Millicent was a pretty girl with pale-brown skin, an oval face, soft features, and none of the awkwardness common to girls her age. “Well, today I went to the Crèche for my afternoon helping the kindergartners to read.”

As part of the charity program I had instituted at Macaulay for girls nine and older, each student spent one afternoon a week at the Fitch Crèche working with preschoolers and kindergartners. The Crèche was one of the prides of the city, the first institution in the nation where poor mothers could bring their children to be cared for during working hours. The children were given meals, baths, education, and even medical examinations.

“On Mondays a lower-school girl named Grace Sinclair comes to the Crèche,” Millicent said. I felt my body tense, and willed myself to relax. I mustn’t show Millicent that I had any special concern for the nine-year-old named Grace Sinclair.

“She draws for the little ones,” Millicent continued, oblivious to my reaction, “and she’s good at it. Today she drew elephants that looked

so real

. Most of the children had never even seen a picture of an elephant! Then she imitated an elephant roaring—Grace is a fine mimic,” Millicent assured me, “and everyone gathered round to hear her.”

Of course I knew Grace could draw well. Of course I knew she was a fine mimic.

“Anyway, Miss Atkins always comes with the lower-school girls, and to keep an eye on us older ones too, I guess.” For the first time Millicent smiled, shyly acknowledging my subterfuge for the supervision of older girls who wanted to believe that they needed no supervision.

“Today,” Millicent said in a thrilled whisper, “Betsy Pratt got sick. She threw up in the cloakroom! It was disgusting! No one could go in there, the smell was so bad. Even after the custodian came to clean it. Miss Barrett—a man went into the girls’ cloakroom! And—”

“Millicent,” I interrupted. Girls this age switched from childhood to adulthood and back again as quick as lightning. “Everyone gets sick at one time or another. There’s no need to make a fuss about it.”

“Sorry, Miss Barrett.” She pouted.

“All right, go on.”

“Well, the matron was upset in case Betsy had a sickness that the little ones might catch, and so Miss Atkins decided to take Betsy home early, right away, even though her frock was still wet because of the”—she glanced at me guiltily—“because of what happened, and even though …”

As Millicent talked on, I felt myself slipping into the suspended animation that was my refuge whenever a young person began to tell me a long and complicated story.

“… and this made a problem because Miss Atkins usually takes Grace Sinclair home herself, because Grace lives near school and Miss Atkins comes back to school after the Crèche. So Miss Atkins asked me if I would take Grace home when we finished at five and I did. We took the electric streetcar partway, and then we walked.”

Now here was something important: entrusting a nine-year-old to a thirteen-year-old. Had Millicent been an Anglo-Saxon girl, Miss Atkins never would have done it. Instead she would have made a telephone call from the Crèche office and arranged for a housekeeper to pick Grace up, or called Grace’s father downtown and asked him to send a sleigh for her. Or, if there’d been no other choice, she would have asked the favor of one of the many girls who lived closer to Grace than Millicent did. But because Millicent was colored, Miss Atkins felt free to treat her like a servant, trusting and exploiting her as she would a servant, by asking her to go blocks out of her way to take another child home.

The city—our neighborhood, that is—was quite safe, but in other parts of town—in the area where the Crèche was located, for example—there had been so many labor strikes, so many layoffs, so much hostility among the foreign groups, I suddenly feared that Millicent was trying to tell me that she and Grace had been assaulted on their way home. A young man roaming his neighborhood, on strike or laid off from his job, or unemployed since leaving school, had seen an opportunity to attack a daughter of the bosses who was out with only a dark-skinned servant girl to protect her. That’s how it would have seemed to him. Or perhaps Millicent herself had been the target, because in our city the only work many colored men could get was as strikebreakers at the factories.