Civilization: The West and the Rest (49 page)

Yet the efforts of the first British missionaries had unintended consequences. The imperial government had sought to prohibit – on pain of death – Christian proselytizing on the ground that it encouraged popular attitudes ‘very near to bring [

sic

] a rebellion’:

The said religion neither holds spirits in veneration, nor ancestors in reverence, clearly this is to walk contrary to sound doctrine; and the common people, who follow and familiarize themselves with such delusions, in what respect do they differ from a rebel mob?

57

This was prescient. One man in particular responded to Christian proselytizing in the most extreme way imaginable. Hong Xiuquan had hoped to take the traditional path to a career in the imperial civil service, sitting one of the succession of gruelling examinations that determined a man’s fitness for the mandarinate. But he flunked it, and, as so often with exam candidates, failure was followed in short order by complete collapse. In 1833 Hong met William Milne, the co-author with Robert Morrison of the first Chinese Bible, whose influence on him coincided with his emergence from post-exam depression. Doubtless to Milne’s alarm, Hong now announced that he was the younger brother of Jesus Christ. God, he declared, had sent him to rid

China of Confucianism – that inward-looking philosophy which saw competition, trade and industriousness as pernicious foreign imports. Hong created a quasi-Christian Society of God Worshippers, which attracted the support of tens of millions of Chinese, mostly from the poorer classes, and proclaimed himself leader of the Heavenly Kingdom of Great Peace. In Chinese he was known as Taiping Tianguo, hence the name of the uprising he led – the Taiping Rebellion. From Guangxi, the rebels swept to Nanjing, which the self-styled Heavenly King made his capital. By 1853 his followers – who were distinguished by their red jackets, long hair and insistence on strict segregation of the sexes – controlled the entire Yangzi valley. In the throne room there was a banner bearing the words: ‘The order came from God to kill the enemy and to unite all the mountains and rivers into one kingdom.’

For a time it seemed that the Taiping would indeed overthrow the Qing Empire altogether. But the rebels could not take Beijing or Shanghai. Slowly the tide turned against them. In 1864 the Qing army besieged Nanjing. By the time the city fell, Hong was already dead from food poisoning. Just to make sure, the Qing exhumed his cremated remains and fired them out of a cannon. Even after that, it was not until 1871 that the last Taiping army was defeated. The cost in human life was staggering: more than twice that of the First World War to all combatant states. Between 1850 and 1864 an estimated 20 million people in central and southern China lost their lives as the rebellion raged, unleashing famine and pestilence in its wake. By the end of the nineteenth century, many Chinese had concluded that Western missionaries were just another disruptive alien influence on their country, like opium-trading Western merchants. When British missionaries returned to China after the Taiping Rebellion they thus encountered an intensified hostility to foreigners.

58

It did not deter them. James Hudson Taylor was twenty-two when he made his first trip to China on behalf of the Chinese Evangelization Society. Unable, as he put it, ‘to bear the sight of a congregation of a thousand or more Christian people rejoicing in their own security [in Brighton] while millions were perishing for lack of knowledge’ overseas, Taylor founded the China Inland Mission in 1865. His preferred strategy was for CIM missionaries to dress in Chinese clothing

and to adopt the Qing-era queue (pigtail). Like David Livingstone in Africa, Taylor dispensed both Christian doctrine and modern medicine at his Hangzhou (Hangchow) headquarters.

59

Another intrepid CIM fisher of men was George Stott, a one-legged Aberdonian who arrived in China at the age of thirty-one. One of his early moves was to open a bookshop with an adjoining chapel where he harangued a noisy throng, attracted more by curiosity than by a thirst for redemption. His wife opened a girls’ boarding school.

60

They and others sought to win converts by using an ingenious new evangelical gadget: the Wordless Book, devised by Charles Haddon Spurgeon to incorporate the key colours of traditional Chinese colour cosmology. In one widely used version, devised by the American Dwight Lyman Moody in 1875, the black page represented sin, the red represented the blood of Jesus, the white represented holiness, and the gold or yellow represented heaven.

61

An altogether different tack was taken by Timothy Richard, a Baptist missionary sponsored by the Baptist Missionary Society, who argued that ‘China needed the gospel of love and forgiveness, but she also needed the gospel of material progress and scientific knowledge.’

62

Targeting the Chinese elites rather than the impoverished masses, Richard became secretary of the Society for the Diffusion of Christian and General Knowledge among the Chinese in 1891 and was an important influence on Kang Yu Wei’s Self-Strengthening Movement, as well as an adviser to the Emperor himself. It was Richard who secured the creation of the first Western-style university, at Shanxi (Shansi), opened in 1902.

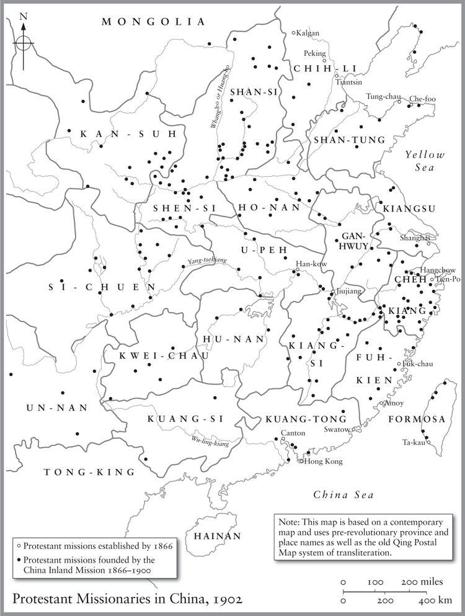

By 1877 there were eighteen different Christian missions active in China as well as three Bible societies. The idiosyncratic Taylor was especially successful at recruiting new missionaries, including an unusually large number of single women, not only from Britain but also from the United States and Australia.

63

In the best Protestant tradition, the rival missions competed furiously with one another, the CIM and BMS waging an especially fierce turf war in Shanxi. In 1900, however, xenophobia erupted once again in the Boxer Rebellion, as another bizarre cult, the Righteous and Harmonious Fist (

yihe quan

), sought to drive all ‘foreign devils’ from the land – this time with the explicit approval of the Empress Dowager. Before the inter

vention of a multinational force and the suppression of the Boxers, fifty-eight CIM missionaries perished, along with twenty-one of their children.

The missionaries had planted many seeds but, in the increasingly chaotic conditions that followed the eventual overthrow of the Qing dynasty, these sprouted only to wither. The founder of the first Chinese Republic, Sun Yat-sen, was a Christian from Guandong, but he died in 1924 with China on the brink of civil war. Then the nationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek and his wife – both Christians

*

– lost out to the communists in China’s long civil war and ended up having to flee to Taiwan. Shortly after the 1949 Revolution, Zhou Enlai and Y. T. Wu drew up a ‘Christian Manifesto’ designed to undercut the position of missionaries on the grounds of both ideology and patriotism.

64

Between 1950 and 1952 the CIM opted to evacuate its personnel from the People’s Republic.

65

With the missionaries gone, most churches were closed down or turned into factories. They remained closed for the next thirty years. Christians like Wang Mingdao, Allen Yuan and Moses Xie, who refused to join the Party-controlled Protestant Three-Self Patriotic Movement, were jailed (in each case for twenty or more years).

66

The calamitous years of the misnamed Great Leap Forward (1958–62) – in reality a man-made famine that claimed around 45 million lives

67

– saw a fresh wave of church closures. There was full-blown iconoclasm during the Cultural Revolution (1966–76), which also led to the destruction of many ancient Buddhist temples. Mao himself, ‘the Messiah of the Working People’, became the object of a personality cult even more demented than those of Hitler and Stalin.

68

His leftist wife Jiang Qing declared that Christianity in China had been consigned to the museum.

69

To Max Weber and many later twentieth-century Western experts, then, it is not surprising that the probability of a Protestantization of China and, therefore, of its industrialization seemed negligibly low – almost as low as a de-Christianization of Europe. The choice for China seemed to be a stark one between Confucian stasis and chaos.

That makes the immense changes of our own time all the more breathtaking.

The city of Wenzhou, in Zhejiang province, south of Shanghai, is the quintessential manufacturing town. With a population of 8 million people and growing, it has the reputation of being the most entrepreneurial city in China – a place where the free market rules and the role of the state is minimal. The landscape of textile mills and heaps of coal would have been instantly recognizable to a Victorian; it is an Asian Manchester. The work ethic animates everyone from the wealthiest entrepreneur to the lowliest factory hand. Wenzhou people not only work longer hours than Americans; they also save a far larger proportion of their income. Between 2001 and 2007, at a time when American savings collapsed, the Chinese savings rate rose above 40 per cent of gross national income. On average, Chinese households save more than a fifth of the money they make; corporations save even more in the form of retained earnings.

The truly fascinating thing, however, is that people in Wenzhou have imported more than just the work ethic from the West. They have imported Protestantism too. For the seeds the British missionaries planted here 150 years ago have belatedly sprouted in the most extraordinary fashion. Whereas before the Cultural Revolution there were 480 churches in the city, today there are 1,339 – and those are only the ones approved by the government. The church George Stott built a hundred years ago is now packed every Sunday. Another, established by the Inland Mission in 1877 but closed during the Cultural Revolution and only reopened in 1982, now has a congregation of 1,200. There are new churches, too, often with bright red neon crosses on their roofs. Small wonder they call Wenzhou the Chinese Jerusalem. Already in 2002 around 14 per cent of Wenzhou’s population were Christians; the proportion today is surely higher. And this is the city that Mao proclaimed ‘religion free’ back in 1958. As recently as 1997, officials here launched a campaign to ‘remove the crosses’. Now they seem to have given up. In the countryside around Wenzhou, villages openly compete to see whose church has the highest spire.

Christianity in China today is far from being the opium of the

masses.

70

Among Wenzhou’s most devout believers are the so-called Boss Christians, entrepreneurs like Hanping Zhang, chairman of Aihao (the Chinese character for which can mean ‘love’, ‘goodness’ or ‘hobby’), one of the three biggest pen-manufacturers in the world. A devout Christian, Zhang is the living embodiment of the link between the spirit of capitalism and the Protestant ethic, precisely as Max Weber understood it. Once a farmer, he started a plastics business in 1979 and eight years later opened his first pen factory. Today he employs around 5,000 workers who produce up to 500 million pens a year. In his eyes, Christianity is thriving in China because it offers an ethical framework to people struggling to cope with a startlingly fast social transition from communism to capitalism. Trust is in short supply in today’s China, he told me. Government officials are often corrupt. Business counterparties cheat. Workers steal from their employers. Young women marry and then vanish with hard-earned dowries. Baby food is knowingly produced with toxic ingredients, school buildings constructed with defective materials. But Zhang feels he can trust his fellow Christians, because he knows they are both hard working and honest.

71

Just as in Protestant Europe and America in the early days of the Industrial Revolution, religious communities double as both credit networks and supply chains of creditworthy, trustworthy fellow believers.

In the past, the Chinese authorities were deeply suspicious of Christianity, and not just because they recalled the chaos caused by the Taiping Rebellion. Seminary students played an important part in the Tiananmen Square pro-democracy movement; indeed, two of the most wanted student leaders back in the summer of 1989 subsequently became Christian clergymen. In the wake of that crisis there was yet another crackdown on unofficial churches.

72

Ironically, the utopianism of Maoism created an appetite that today, with a Party leadership that is more technocratic than messianic, only Christianity seems able to satisfy.

73

And, just as in the time of the Taiping Rebellion, some modern Chinese are inspired by Christianity to embrace decidedly weird cults. Members of the Eastern Lightning movement, which is active in Henan and Heilongjiang provinces, believe that Jesus has returned as a woman. They engage in bloody battles

with their arch-rivals, the Three Grades of Servants.

74

Another radical quasi-Christian movement is Peter Xu’s Born-Again Movement, also known as the Total Scope Church or the Shouters because of their noisy style of worship, in which weeping is mandatory. Such sects are seen by the authorities as

xiejiao

, or (implicitly evil) cults, like the banned Falun Gong breathing-practice movement.

75

It is not hard to see why the Party prefers to reheat Confucianism, with its emphasis on respect for the older generation and the traditional equilibrium of a ‘harmonious society’.

76

Nor is it surprising that persecution of Christians was stepped up during the 2008 Olympics, a time of maximum exposure of the nation’s capital to foreign influences.

77