Climbing Up to Glory (15 page)

Read Climbing Up to Glory Online

Authors: Wilbert L. Jenkins

The arrival of Union soldiers in rural areas witnessed much excitement among freedmen. Colonel Thomas W. Higginson, a white officer in the First South Carolina Volunteers, the first slave regiment mustered into the service of the United States, described the reaction of blacks on Edisto Island to the arrival of his regiment. “What a sight it was! With the wild faces, eager figures, and strange garments, it seemed, as one of the poor things reverently suggested, âlike notin' but de Judgment Day.'” Higginson noted that “presently they began to come from the houses also with bundles of all sizes on their heads.” Old women trotting down the narrow paths would kneel to say a little prayer “still balancing the bundle.... Then they would suddenly spring up, urged on by the accumulating procession behind.” Higginson continued: “They would move on till they were irresistibly compelled by thankfulness to dip down for another prayer.” But, as he perceived it, the most moving scene occurred when the freedmen reached the soldiers, for at this point “our hands were grasped and there were exclamations of âBress you, masr',' and âBress de Lord.' ” Women brought children on their shoulders. “Small black boys came, carrying on their backs their little black brothers whom they gravely deposited on the ground, then turned to shake our hands.”

56

Indeed, in the minds of these rural blacks, this was their long-awaited day of deliverance.

Like former rural slaves, most former urban ones left the houses where they had been enslaved when they first received news of their freedom. They departed because these dwellings symbolized slavery and they wanted to remove themselves from any reminders of the institution. They were also motivated by the constant desire to assert and test their newfound freedom. One black cook, though satisfied in her position, resigned because “it look like old time to stay too long in one place.”

57

A native white Charlestonian who lived in a household just north of the city reported incredulously in the spring of 1865 that most of the servants “say they are free and went off last night.” These even included “one Uncle Henry trusted most.”

58

Widespread desertion by urban former slaves was particularly true of domestics, a group that had constituted the bulk of urban slaves prior to the Civil War. In fact, they deserted in such large numbers that one contemporary newspaper described domestics as “perfect nomads” who seldom remained in a family's service for any appreciable time.

59

White owners saw only that their former slaves were leaving material security for uncertainty. Apparently, most whites did not grasp the nature of the anger, frustration, and anxiety experienced by urban domestics. Their every move was watched by white owners, they often had to work long hours, and, in addition, they had to answer their master's every beckon and call. They were essentially on the job for twenty-four hours per day. Moreover, despite the fact that their work was usually less arduous than that of the field hands and that close proximity to owners bred relationships based on genuine affection, there was a negative side. Domestics were often in a position to observe on a firsthand basis the huge discrepancies between slaves and whites in terms of food, shelter, clothing, and personal belongings. They knew the enemy all too well.

Many of the former slaves who migrated to cities and towns arrived there with conquering Federal troops and shared in the excitement of the Union triumph with former urban slaves. On the morning of December 21,1864, soon after the Confederates evacuated Savannah, Union forces led by General William Tecumseh Sherman marched into the city accompanied by their corps of black laborers and followed by a long train of more than ten thousand former slaves. Most were cheering and dancing. The city's blacks gave Sherman a welcome that was “singular and touching,” greeting his arrival, wrote George Ward Nichols, “with exclamations of unbounded joy.” One elated black woman grabbed the general's hand and made a short thank-you speech.

60

John Gould noted that when Sherman's troops entered Savannah, “swarms of black children followed his troops through the city.” Another Union soldier spoke to a freed black woman who summed up her emotions by exclaiming, “It is a dream, sirâa dream!”

61

Spotted outside the window of a white woman was a young black girl jumping up and down and singing as loudly as she could, “All de rebel gone to hell, now Pa Sherman come.”

62

Union troops liberating the city of Charleston inspired similar jubilation. Black soldiers were among the first Union units to enter Charleston after the Confederate evacuation, and their arrival ignited an explosion of adulation among the black population. As the all-black Fifty-fifth Massachusetts entered the city, “shouts, prayers, and blessings came from the former slave population,” according to a contemporary observer, who also noted a touching scene. One black soldier, holding aloft a banner proclaiming “Liberty,” rode a mule down Meeting Street at the head of an advancing column. A black woman shouting “Thank God! Thank God!” dashed over to hug him but missed her mark and hugged the mule instead. Several other blacks were so overcome with emotion that they wept.

63

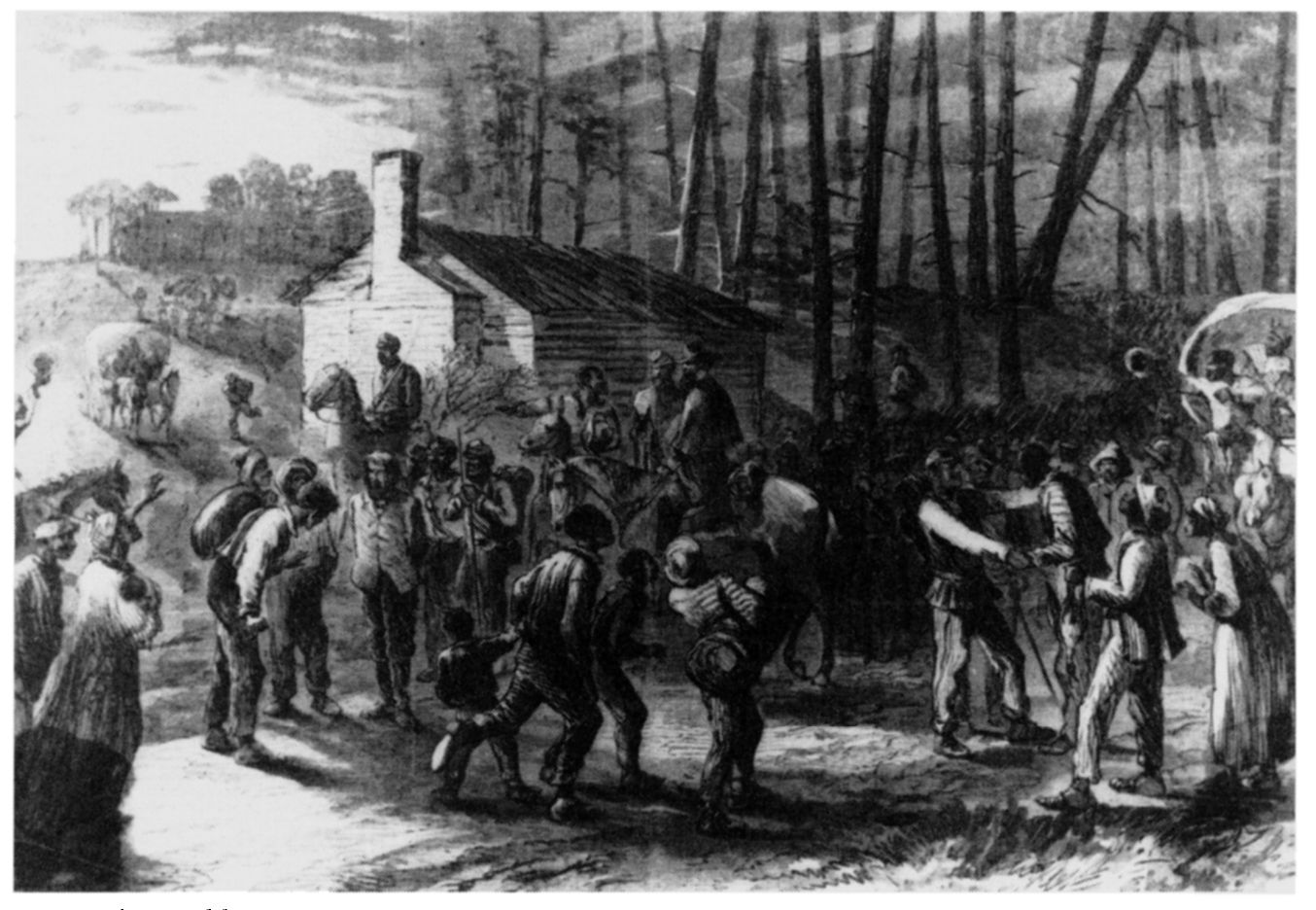

BLACK UNION SOLDIERS LIBERATING SLAVES IN NORTH CAROLINA.

Harper's Weekly,

January 23,1864

To white Charlestonians the presence of black troops was unsettling, particularly since the Third and Fourth South Carolina regiments that joined the Twenty-first U.S. Colored Troops and the Fifty-fourth and Fifty-fifth Massachusetts black regiments in liberating the city were made up of former slaves from the Charleston area. The liberation by black troops of Charleston, the bastion of the secession movement, was a deliberate ploy by the Federal government to psychologically and emotionally wreak as much havoc as possible. Indeed, the city had to pay a heavy price for its role in bringing on the Civil War. Wendell Phillips, a white abolitionist from Massachusetts, captured the sorrow felt by most white Charlestonians when he asked: “Can you conceive a bitterer drop that God's chemistry could mix for a son of the Palmetto State, than that a Massachusetts flag and a colored regiment should take possession of Charleston?”

64

For whites in Charleston it was a novel experience to have blacks not give them “the inside of the [side]walk” and to have a black man address them without first doffing his hat. The sight of black sentinels stationed at public buildings to examine the passes of all who would enter was especially depressing to whites. Black soldiers made up the provost guards, charged with maintaining law and order and quartered at the Citadel, and “whoever desired protection papers or passes, whoever had business with the marshal or the general commanding the city, rich or poor, high-born or low-born,

white or black,

man or woman,” wrote Charles Coffin, “must first meet a colored sentinel face to face, and obtain from the colored sergeant permission to enter the gate.”

65

Having lost the war, it now appeared to injured white Charlestonians that the North was rubbing salt in the wound.

Mrs. Frances J. Porcher, a prominent white South Carolinian, described the changed situation in a wry letter to a friend: “Nat Fuller, a Negro caterer, provided munificently for a miscegenat dinner, at which blacks and whites sat on an equality, and gave toasts and sang songs for Lincoln and Freedom. Miss Middleln and Miss Alston, young ladies of colour, presented a coloured regiment with a flag on the Citadel green, and nicely dressed black sentinels turn back white citizens, reprimanding them for their passes not being correct.”

66

To freedmen, it was a day that they had prayed for and long awaited.

As in Charleston, black troops were among the first Union soldiers to enter the city of Richmond. The gallant 36th U.S. Colored Troops, under Lieutenant Colonel B. F. Pratt, was the first to arrive. The regiment's drum corps played “Yankee Doodle” and “Shouting the Battle Cry of Freedom” amid the cheers of the boys and the white soldiers who filed by them.

67

The all-black Fifth Massachusetts Cavalry next rode in with two white regiments, followed by Companies C and G of the Twenty-ninth Connecticut Colored Volunteers and Ninth U.S. Colored Troops. And here, too, the black residents of the city were ecstatic, running along the sidewalks to keep up with the troops, while other residents stood gasping in wonder as the Union soldiers marched through the streets.

68

Thomas Morris Chester, the Northern black war correspondent, captured the moment: “Some waved their hats and women their hands in token of gladness.” According to Chester, newly freed blacks in Richmond expressed their joy and appreciation to the Union army in such phrases as: “You've come at last,” “We've been looking for you these many days,” “Jesus has opened the way,” “God bless you,” “I've not seen that old flag for four years,” “It does my eyes good,” “Have you come to stay?” and “Thank God.”

69

Shortly before this electrifying scene took place, however, another emotional scene transpired. Chaplain Garland H. White, who had been born and raised nearby as a slave, was among the first troops entering Richmond. He was asked to make a speech, to which he complied. As he wrote, “I was aroused amid the shouts of ten thousand voices, and proclaimed for the first time in that city freedom to all mankind.”

70

A few hours later, a large crowd of black soldiers and residents assembled on Broad Street near Lumpkin Alley, where the slave jails, auction rooms, and offices of the slave traders were concentrated. Encouraged by the presence of black troops, the slaves held in Lumpkin's jail began to chant: “Slavery chain done broke at last! Broke at last! Broke at last! Slavery chain done broke at last! Gonna praise God till I die!” When the crowd outside took up the chant, the soldiers opened the cells and the prisoners came pouring out, some praising God and “Master Abel” for their deliverance.

71

The highlight of the first day of the Union occupation of Richmond was the visit to the city of President Abraham Lincoln. As soon as he arrived on April 3, 1865, the news quickly spread. Some free blacks shouted that the president had arrived. But the title “president” was associated with Jefferson Davis in the South, so initially most blacks did not realize that Lincoln was in the city. Rumors had circulated that Davis had been captured and was being brought to Richmond for punishment. As they approached the visitor, they cried out in anger, “Hang him! Hang him! Show him no quarter!”

72

Davis represented to most blacks the embodiment of the pro-slavery South. Indeed, one of the most popular tunes sung by both black civilians and soldiers went something like this: “Hang Jeff Davis on a sour apple tree, Hang Jeff Davis on a sour apple tree, Hang Jeff Davis on a sour apple tree, As we go marching along.”

73

When blacks discovered that the visitor was Lincoln and not Davis, they were thrilled. In only a few minutes, there were thousands of freed people trying to catch a glimpse of Lincoln. Later, as the president was preparing to depart, one contemporary, overtaken by emotion, asserted that “there is no describing the scene along the route. The colored population was wild with enthusiasm. Old men thanked God in a very boisterous manner, and old women shouted upon the pavement as high as they had ever done at a religious revival.”

74

Foreshadowing what would be the gloomy fate of Lincoln in only a few days, as his ship sailed off amid the cheering of the crowd, a black woman cried out, “Don't drown, Massa Abe, for God's sake!”

75

The Union occupation of Richmond represented the beginning of freedom for blacks, but it was a nightmare for the city's whites. It was bad enough that the conquering Union troops were patrolling the streets, but worse still that black soldiers were among them. For most whites, it seemed as if the victorious North had conspired to make the occupation as distasteful as possible. The sight of long lines of black cavalry sweeping by the Exchange Hotel, raising their swords in triumph and exchanging cheers with black residents, was intolerable.

76

The anguish felt by Richmond whites and those throughout the South over the changed state of affairs is illustrated by a confrontation between a black Union soldier, who had earlier been a slave in the area, and his former owner. The black man was one of several guards escorting through the streets a large squad of rebels, which happened to include the white master. When he spotted his former slave, he stepped a little out of ranks and called, “Hello, Jack, is that you?” The black guard stared at him with a look of blank astonishment, not unmingled with disdain. The rebel captive still was determined to be recognized and asked, “Why, Jack, don't you know me?” “Yes, I know you very well,” was the sullen reply, “and if you don't fall back into that line I will give you this bayonet.” This reply, of course, terminated any attempts at familiarity.

77