Climbing Up to Glory (5 page)

Read Climbing Up to Glory Online

Authors: Wilbert L. Jenkins

On the day that the Emancipation Proclamation was issued, it did not free one slave. Technically it freed slaves in the South, but the U.S. government could not make this act binding until after the Confederacy was defeated. The Proclamation did not even claim to free the slaves in the Border states of Missouri, Kentucky, Maryland, and Delaware. Likewise, it exempted those working on plantations in areas occupied by federal forces, such as the Mississippi Valley and the Sea Islands, where many owners had taken an oath of allegiance and pledged their “loyalty” to the federal government. It was the Thirteenth Amendment, approved by Congress in February 1865 and ratified the following December, that actually emancipated all the slaves.

The Emancipation Proclamation was of critical importance, however, in meeting Lincoln's manpower goals for the Union military by encouraging slaves to escape and take up arms. Although the first black troops were mustered into service in the fall of 1862, recruitment did not begin in earnest until the spring of 1863, after the proclamation had been issued. In the occupied areas of the South where enlistment drives were launched, many slaves responded enthusiastically.

69

As Solomon Bradley of South Carolina put it, “I used to pray the Lord for this opportunity to be released from bondage and to fight for my liberty, and I could not feel right so long as I was not in the regiment.”

70

And in the North, blacks welcomed the chance to fight for their freedom and for that of their families. The Proclamation also strengthened the moral cause of the Union at home and abroad. It rallied the North by adding the idealistic appeal of a war being fought not only to preserve the Union but also to free the slaves. Before Lincoln issued the Proclamation, there was a real possibility that European powers, led by Britain, might formally recognize the Confederacy and intervene militarily on its behalf. But that all changed with the stroke of a pen. The Proclamation turned out to be a shrewd diplomatic move. Thousands of English and European laborers who were anxious to see workers gain their freedom throughout the world perceived that the Union was fighting to free black workers, while the Confederacy was fighting to keep them in bondage.

71

Lincoln remained undaunted in the face of relentless attacks against the Proclamation. The president stood foursquare behind it. The pressure from his numerous critics got to him; he wavered but did not buckle. Instead, he told weakened Republicans that “no human power can subdue this rebellion without using the emancipation lever as I have done.” Lincoln was also quick to dismiss any suggestions that he return to slavery those blacks who had fought for the Union. To the whites who dared propose this, Lincoln passionately replied, “I should be damned in time and in eternity for so doing. The world shall know that I will keep my faith to friends and enemies, come what will!” Lincoln made this statement in the midst of strong political opposition to his emancipation policies on the eve of the 1864 presidential election, which he clearly expected to lose. In effect, he was saying that he would rather be right than president. As matters turned out, of course, he was both right and president,

72

and the nation as a whole benefited from his dual triumph. First, issuing the Emancipation Proclamation was an excellent moral and ethical decision of paramount importance to humanity. Despite any strategic and political dividends that might come to him, the fact that Lincoln stood forthright behind it is noble. And, second, he certainly deserved the opportunity to lead the country to the successful completion of the war. At this point in the nation's history, no other person was better equipped than Lincoln to guide the country through its national nightmare. That the country fully understood this, and reelected him to the presidency in 1864, was indeed a triumph for the nation.

Realizing that preservation of the Union was tied to black emancipation, Lincoln endorsed the Thirteenth Amendment abolishing slavery even before the election of 1864. When Lincoln and the Republicans won large majorities at the polls, the president moved immediately to get Congress to pass the emancipation amendment. In fact, he began pressuring Congress to act in December 1864, only a few days after the election. As Lincoln viewed it, the large majorities that the Republicans won at the polls, including Democratic votes, had dampened the morale of the Confederacy. And, passage of an emancipation amendment, Lincoln believed, especially by the slave states, would further erode its morale. As he told Missouri Democrat James Rollins, “I am very anxious that the war be brought to a close at the earliest possible date. I don't believe this can be accomplished as long as those fellows down South can rely on the border states to help them; but if the members of the border states would unite, at least enough of them to pass the amendment, they would soon see that they could not expect much help from that quarter.” Lincoln believed that he was now operating from a position of strength and insisted that the national election had given him a mandate for permanent emancipation. Perhaps the current political climate would help shift the necessary votes in the House in his direction. If not, the next House would surely provide enough votes.

73

Momentum seemed to be on the president's side in the days just prior to the vote, but a last-minute rumor threatened to stop it. A rumor swept through the Capitol that Southern commissioners were on their way to Washington for peace talks. If this was true, some who had announced their intentions to support the amendment might recant, particularly those representatives from the Border slave states. From their vantage point, why emancipate slaves to save the Union if one could save the Union without emancipation? In a last-ditch effort to hold the votes in line, James Ashley, who was in charge of the measure on the floor of the House, asked Lincoln to issue a direct denial of the rumor. Lincoln readily assented with a one-sentence response: “So far as I know, there are no peace commissioners in the city, or likely to be in it.”

74

There was considerable suspense on January 31, 1865, the day of the vote. No one could be certain of the outcome. Spectators filled the corridors and galleries of the Capitol to observe history in the making. The Thirteenth Amendment abolishing the institution of slavery passed with the necessary two-thirds votes. All 102 Republicans, joined by seventeen Democrats, voted for the amendment. Some fifty-eight Democrats voted no on the measure, and eight Democrats helped out by abstaining. The final tabulation represented just three votes more than the required two-thirds majority.

75

Success, at long last Lincoln's, had taken all of the resources at his disposal to make the Thirteenth Amendment a reality. Indeed, the president lent his talents of eloquence to this effort as well as his political skills, engaging in secret patronage negotiations. As expected, blacks greeted news of the passage of the amendment with unbounded joy. They gathered in mass meetings and clapped and sang: “Sound the loud timbrel o'er Egypt's dark sea, Jehovah has triumphed, His people are free.”

76

In the White House, Lincoln pronounced the amendment “a great moral victory.” And, beaming, he pointed south across the Potomac and remarked, “if the people over the river had behaved themselves, I could not have done what I have.”

77

Sadly, within three short months after this “crowning achievement,” Lincoln would be dead, the victim of an assassin's bullet. Although his voice was silenced, his contributions to humanity would live on. The Emancipation Proclamation and his subsequent efforts on behalf of the Thirteenth Amendment represented the pinnacle of his heroic legacy: the substance of his image as the Great Emancipator. However, although Lincoln had been an indispensable player in the black liberation drama, his primary concern was for the Union. Therefore, as Frederick Douglass noted, Lincoln's image as the Great Emancipator was somewhat exaggerated. Nevertheless, in spite of his shortcomings, he was a vital agent in an inexorable progression of circumstances that would result in the total abolition of slavery.

78

Lincoln's presidency ushered in a period of symbolic advancement for blacks. For example, on the very day that the House passed the Thirteenth Amendment, the chamber's galleries were packed with cheering blacksâone of the first times that they were allowed to sit in the galleries. Blacks had been denied entry until 1864. And, on February 1, 1865, history was again made. For the first time in the country's history, a black lawyer from Boston, John S. Rock, was admitted to practice before the U.S. Supreme Court.

79

Yet prior to these events, Lincoln had begun to show more sensitivity and respect in his attitude toward blacks. For example, as no president before him had done, Lincoln opened the White House to black visitors; four black men were in attendance at the New Year's Day reception in 1864. Frederick Douglass met him several times at the Soldiers Home, paid at least three calls at the White House, and made his last visit as a guest at the reception on the night of the second inauguration.

80

Accompanied by her fourteen-year-old grandson, Sammy Banks, Sojourner Truth went to Washington in the fall of 1864, where on October 20 she met the president. Lincoln also complied with a request from a delegation of black clergymen to meet with him at the White House. The clergymen sought and were granted permission to preach to black soldiers.

81

Frederick Douglass, who had more contact with Lincoln than any other black, summed up the legacy of his presidency in regard to black freedom in his “Oration in Memory of Abraham Lincoln” given on April 14,1876, at the unveiling of the Freedmen's Memorial Monument in Washington, DC. Douglass gave Lincoln due credit for eradicating slavery. Nonetheless, he saw the president as primarily pro-Union and pro-white and only unwittingly pro-black. Douglass maintained that “Abraham Lincoln was not, in the fullest sense of the word, either our man or our model.” Further, Douglass asserted, “in his interests, in his associations, in his habits of thoughts, and in his prejudices, he was a white man.” White Americans were “the children of Abraham Lincoln,” but black Americans were at best only his stepchildren, children by adoption, children by forces of circumstance and necessity.

82

In the end, therefore, Lincoln ought to be best remembered as a reluctant friend of blacks.

UNWANTED PARTICIPANTS

Service in the War

Â

Â

Â

Â

ONCE BLACKS WERE finally permitted to enlist in the Union army, they reacted with enthusiasm. Popular black leaders such as Frederick Douglass, William Wells Brown, Charles L. Remond, Martin Delany, John M. Langston, Henry Highland Garnet, John S. Rock, Mary Ann Shadd Cary (the only woman officially commissioned as a recruiting agent), and others were called upon to serve as recruiters in the North. In Boston, New York, Philadelphia, and other cities, rallies were organized where speakers urged blacks to enlist, and blacks responded by appearing in huge numbers at recruiting stations. Mary Ann Shadd Cary, who was working as a teacher in Canada to support her two children, was encouraged by her dear friend Martin Delany to become a recruiter and secured soldiers for Connecticut, Indiana, and Massachusetts regiments. That she succeeded in this effort came as no surprise to her contemporaries. William Wells Brown wrote that “she raised recruits with as much skill, tact, and order as any government recruiting officer and that her men were always considered among the best recruited.”

Although Shadd Cary was the only woman officially commissioned, she was by no means the lone woman recruiter. As the war progressed, many of the black male recruiters expanded their work into Canada and Union-held territory in the South. In these endeavors they were aided by black women such as Josephine Ruffin in Boston, who had recently married, and Harriet Jacobs, who wrote from Alexandria, Virginia, “I hope to obtain some recruits for the Massachusetts Cavalry, not for money, but because I want to do all I can to strengthen the hands of those who battle for freedom.”

1

Indeed, the rationale given by Jacobs expresses the sentiments of most black recruiters. Douglass, Garnet, Wells Brown, Langston, Remond, Delany, Shadd Cary, and others had devoted a lifetime of energy and sacrifice to eradicate the institution of slavery and promote racial justice. Thus, their efforts to secure black soldiers represented their ongoing commitment to excise the cancer of racial oppression from American society. In their minds, the recruitment of a large black liberation force was of paramount importance.

In the South, where the situation was more tenuous, some blacks did not see any need to fight as long as they were winning their freedom without doing so,

2

but many in this region did enlist. Some plantation owners lost nearly all their enslaved field workers. When Admiral David D. Porter visited a plantation twenty miles above Vicksburg, Mississippi, late in 1864, for example, he found only one black out of a former population of nearly four hundred. “Uncle Moses,” with whom he had conversed on a previous visit many months earlier, informed him that all the young “bucks” had gone to join the army or enlist on board “Mr. Linkum's gunboats.”

3

George Washington Albright asserted that “like many other slaves, my father ran away from his plantation in Texas and joined the Union forces.”

4

And Julius Jones recalled, “when the war came on, I must have been fourteen years old. All the men on the place run off and joined the Northern army.”

5

Moreover, March Wilson, of Sapelo Island, Georgia, walked several miles north to Port Royal Island, South Carolina, to enlist in the Union army on December 2, 1862. He became a member that day of the South Carolina Volunteers, the first Union regiment composed of former slaves.

6

Wilson was certainly only one of many blacks from his area to enlist at the earliest opportunity. Indeed, black recruitment efforts were so successful that by the end of the war more than 186,000 had enrolled in the Union army. Ninety-three thousand came from the seceded states and 40,000 from the Border slave states, with the other 53,000 from the free states.

7

Among these black soldiers were several who had emigrated to Canada and then returned to the United States to fight on the Union side during the war.

8

Perhaps the total figure was even higher because some contemporaries insisted that many mulattoes, the offspring of black and white unions, served in white regiments without being designated as blacks.

9

Black troops were organized into regiments of light and heavy artillery, cavalry, infantry, and engineers. To distinguish them from white soldiers, they were called “United States Colored Troops.” They were usually led by white officers with the aid of some black noncommissioned officers. Since most whites in the Union army were opposed to having blacks in the service, it was difficult at first to secure white officers for black outfits. Nevertheless, among those who distinguished themselves as fine leaders were Colonel Robert Gould Shaw of the Fifty-fourth Massachusetts Regiment and General N. P. Banks of the First and Third Louisiana Native Guards.

10

Thomas Wentworth Higginson, colonel of the First South Carolina Volunteers, spoke proudly about the ability of his men. After a successful raid in Florida in 1863, he stated with passion, “Nobody knows anything about these men who has not seen them in battle. There is a fierce energy about them.”

11

By the end of the war, black men had fought courageously in so many engagements that it was no longer difficult to solicit whites to command them.

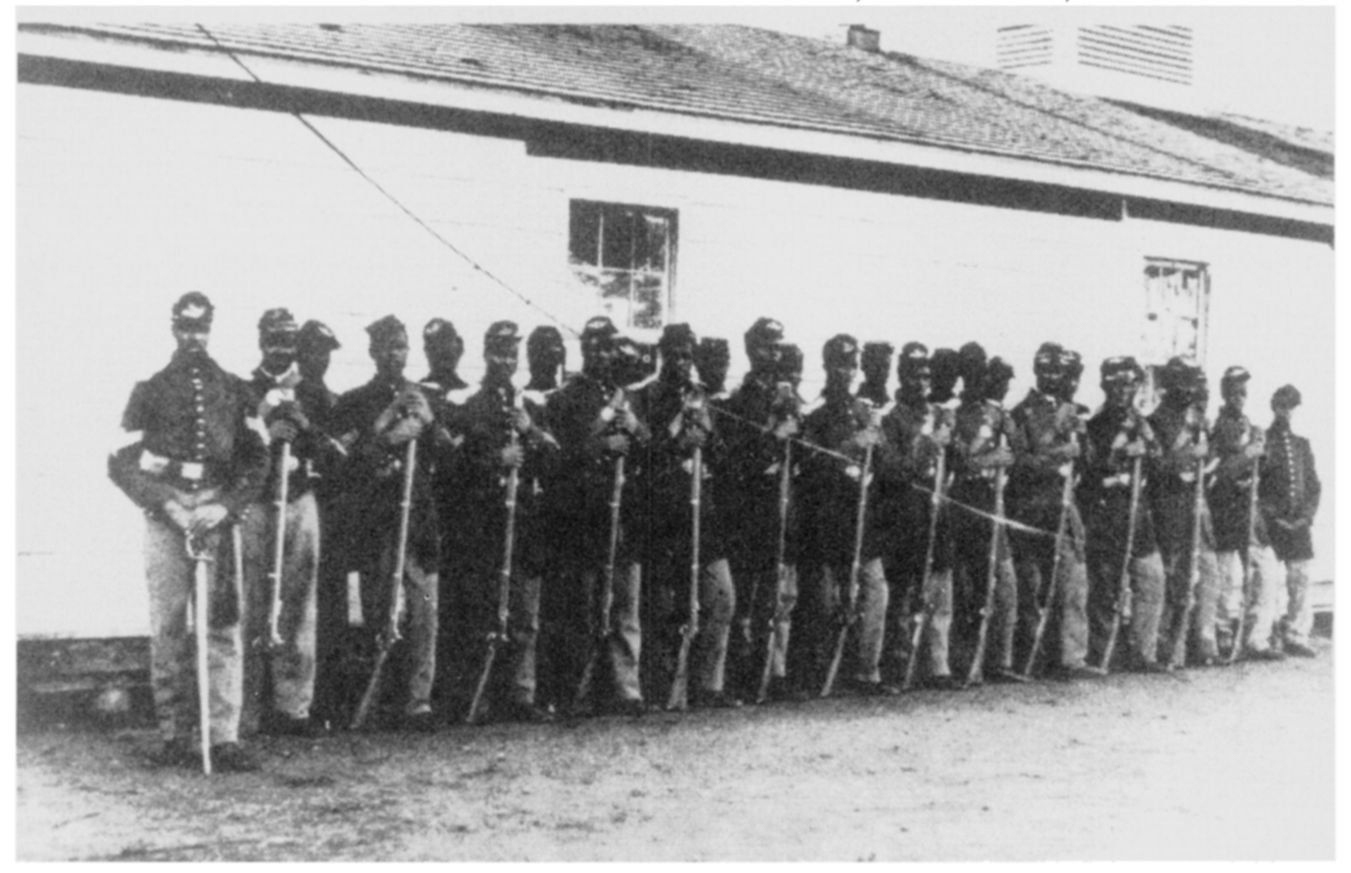

PRIVATES AND NONCOMMISSIONED OFFICERS AT FORT STEVENS, WASHINGTON, DC.

Library of Congress

A few blacks held commissions in the Union army. Two regiments of General Benjamin Butler's Corps d'Afrique were staffed entirely by black officers; among them were Major F. E. Dumas and Captain P. B. S. Pinchback. Captain H. Ford Douglass and First Lieutenant W. D. Matthews led an independent battery at Lawrence, Kansas. Major Martin R. Delany and Captain O. S. B. Wall were officers in the 104th Regiment. Among the commissioned officers were black chaplains, including Henry M. Turner, William Hunter, James Underdue, Williams Waring, Samuel Harrison, William Jackson, and John R. Bowles, and black surgeons, including Alexander T. Augusta of the Seventh Regiment, and John V. DeGrasse of the Thirty-fifth. Other black surgeons who served but were not commissioned included Charles B. Purvis, Alpheus Tucker, John Rapier, William Ellis, Anderson Abbott, and William Powell.

12

The fact that such a small number of blacks held commissions in the Union army greatly upset many black soldiers, who regarded this as a blatant example of racial injustice. They reasoned that only the color of their skin was the deciding factor, as they knew deserving competent blacks who would make outstanding officers. Many black soldiers, therefore, were quick to launch protests in writing regarding the army's failure to commission blacks as officers in significant numbers. An anonymous soldier in the Fifty-fourth Massachusetts Infantry wrote about the outstanding performance of a black doctor in saving the life of a captain in his regiment. So many people were impressed that there was a petition circulated in support of his promotion. In fact, all the officers signed the petition except three, and even they admitted that “he was a smart man and understood medicine.” Nonetheless, in their opinion, “he was a negro and they did not want a negro doctor, neither did they want negro officers.” As a consequence of this prejudice among his officers, the colonel felt compelled to destroy the document.

13

In a letter filled with hurt and disappointment, an anonymous soldier in the Fiftv-fifth Massachusetts Infantry asked, “If we have men in our own regiment who are capable of being officers, why not let them be promoted the same as other soldiers?” He was sickened by the army's tendency to take sergeants from white regiments and make them captains or lieutenants, and then place them in charge of blacks.

14

A sergeant in the Fifty-fourth Massachusetts Infantry wrote, “We want black commissioned officers; and only because we want men we can understand and who can understand us. We want men whose hearts are truly loyal to the rights of man.” He deemed it necessary to have ample black representation in case of courts-martial, where many blacks would undoubtedly end up. Speaking for many black soldiers, he explained: “We want to demonstrate our ability to rule, as we have demonstrated our willingness to obey.” And, zeroing in on the racism of white officers in his regiment, the sergeant concluded, “Can they have confidence in officers who read the Boston Courier and talk about âNiggers'?”

15

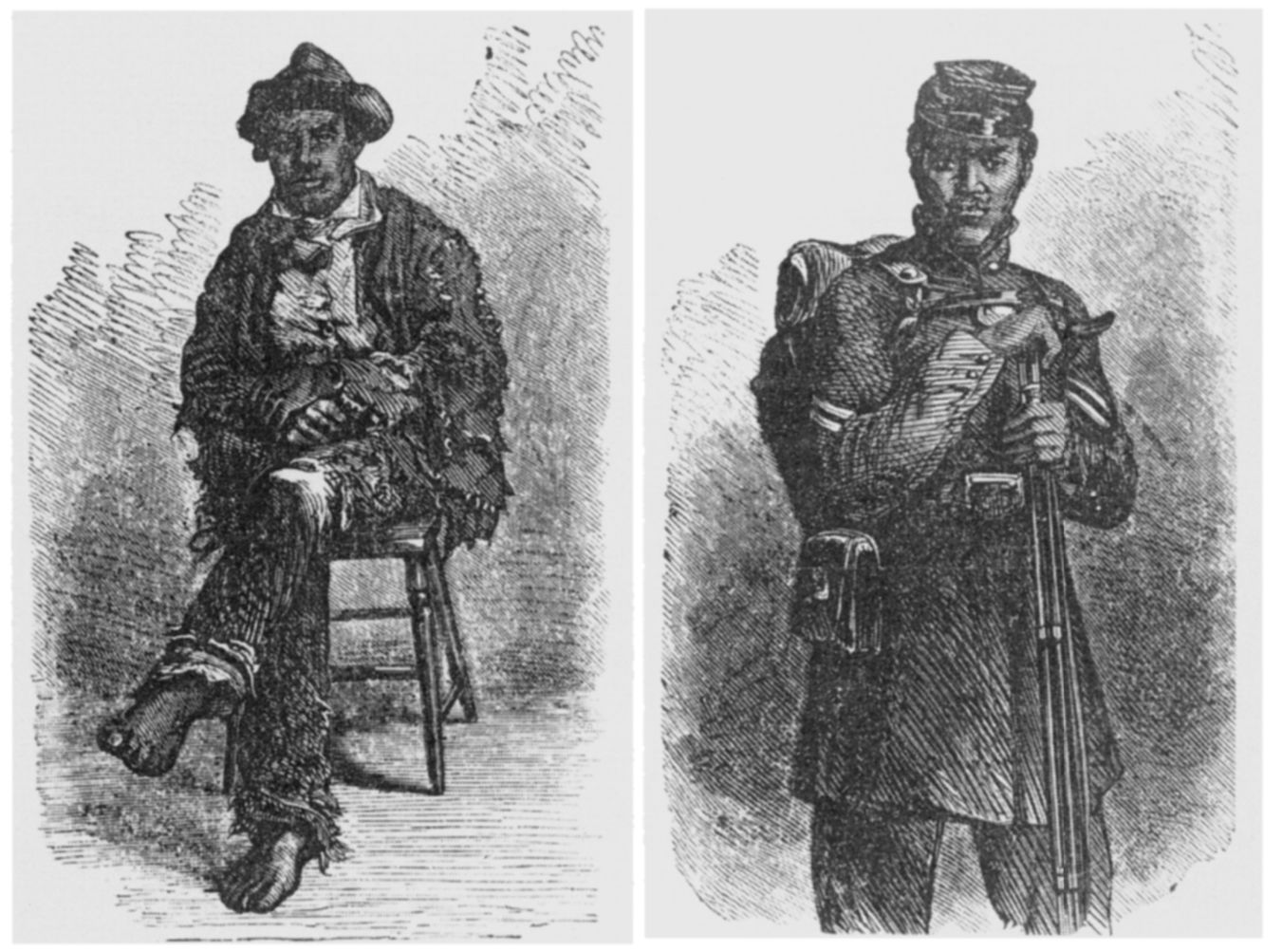

An unidentified Black Union soldier. Courtesy of N.C. Division of Archives and History

Notwithstanding all these grievances, black soldiers did not lose perspective. Even with the white racism and discrimination that they had to endure, most were quick to point out, “we prefer the Union rather than the rebel government, and will sustain the Union if the United States will give us our rights.” Furthermore, they maintained, “we will calmly submit to white officers, though some of them are not as well acquainted with military matters as our orderly sergeants.”

16

In other words, they would carry out their duties in a disciplined and dignified way despite their concerns. Although the tenor of most of their letters was forceful, they were also respectful, with one man concluding, “I hope sir, that you will urge this matter, as I am well aware that you are on our side, and always have done for us all in your power to help our race.”

17

Black soldiers were on target in their thinking that if more black men were commissioned as officers, a more harmonious atmosphere would ensure in the army, and the end result would be equal justice for all. In most cases, however, not only were they unable to increase substantially the number of black commissioned officers, but the intense racism of many white officers also drove some of the few commissioned officers from the army. For example, Robert H. Isabelle, a lieutenant in the Second Louisiana Native Guards, one of only three black regiments led by men of color, resigned from the army. The reason was racism: “I joined the United States Armyâwith the sole object of laboring for the good of our country,” he wrote, “but after five or six months experience I am convinced that the same prejudice still exist[s] and prevents that cordial harmony among officers which is indispensable for the success of the army.”

18

Unfortunately, Isabelle's resignation was soon followed by those of other black officers.

The fervent racism that forced Isabelle and others out of military service took various forms. Black soldiers were often served barely adequate food that had earlier been rejected by white troops and then sent to them. Benjamin Williams, a young private in the Thirty-second U.S. Colored Infantry, claimed that the rations served to them were “moldy and musty and full of worms, and not fit for a dog to eat.” When the men returned to camp for dinner, “there is nothing to eat but rotten hard tack and flat coffee without sugar in it.”

19

In addition, racism sometimes took the form of derogatory language. Such was the case involving a white officer in the Fifty-fifth Massachusetts Infantry, who called one of the regiment's soldiers a “nigger.” As expected the black solider was offended and threatened to retaliate. The white officer then hid on a nearby ship. Just when it appeared that a group of black soldiers would force the white man off the ship and beat him, Colonel Fox, the commanding officer, arrived on the scene. The colonel assured the men that justice would be done and then ordered the officer to “come out and give a reason why he should call a soldier a nigger.” When he failed to respond satisfactorily, Colonel Fox “ordered him under arrest, and sent him, accompanied by at least two files of good brave colored soldiers, to report to the Provost guard.”

20

Cases of racism involving poor food and the use of derogatory language paled in comparison to the random violence wreaked upon black soldiers by white officers. Many of these officers, once enlisted men in white regiments, occupied the very positions of leadership that several blacks continued to argue rightfully belonged to competent members of their race. A private in the Forty-third U.S. Colored Infantry, for example, wrote a letter condemning their actions: “Our officers must stop beating their men across the head and back with their swords.” And, he warned, if they do not, “I fear there will be trouble with some of us. There are men in this regiment who were born free, and have been brought up as well as any officer in the 43d, and will not stand being punched with swords and driven around like a dog.”

21

The most notorious case of mistreatment involved Lieutenant Colonel Augustus W. Benedict of the Seventy-sixth U.S. Colored Infantry, whose conduct could be ruthless. Benedict tied an alleged guilty soldier with his arms and legs spread apart to stakes driven into the ground and smeared molasses on his face, hands, and feet to attract insects. The man was left there for an entire day, and the entire process was repeated the next day. On two other occasions, Benedict struck one soldier and severely whipped two drummer boys. He was ultimately court-martialed and dismissed from the service.

In another case, authorities were forced to press charges against a lieutenant who abused his troops, usually for trifling reasons. During his short tenure, the lieutenant had tied up four soldiers for prolonged periods of time, one of them for complaining to the regimental commander that he had no rations. He clubbed a private with his revolver three times and punched him once; he also struck another man during battalion drill. In addition, in the Thirty-second U.S. Colored Infantry, abuse occurred so often that one of its black soldiers threatened to eliminate the officers in his company: “I know that some of us have left our homes, only to be abused and knocked about; but one consolation is left us, we have their own clubs that they gave us, to break their own heads with; and, in short, they are making a trap to enslave themselves in.”

22

Retaliation was a common response to white violence, as black soldiers often refused to accept injustices without a fight.

There was no theater of operations during the Civil War in which blacks did not see action. They fought in 449 engagements, thirty-nine of which were major battles. They were at the siege of Savannah in Georgia, at Vicksburg in Mississippi, at Olustee in Florida, and at Milliken's Bend in Louisiana. They fought in Arkansas, Kentucky, Tennessee, and North Carolina, and when General Lee surrendered to Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Court House they were there too. Decatur Dorsey was awarded a Congressional Medal for gallantry while acting as color-sergeant of the Thirty-ninth U.S. Colored Troops at Petersburg, Virginia, on July 30, 1864. Private James Gardner of the Thirty-sixth was awarded a medal for rushing in advance of his brigade to shoot a Confederate officer who was leading his men into action. Four men of the Fifty-fourth Massachusetts Infantry earned the Gillmore Medal for gallantry displayed in the assault on Fort Wagner in South Carolina in which their commanding officer, Colonel Robert Gould Shaw, a trusted and respected friend of black soldiers, was killed.

23

When the Fifty-fourth Massachusetts was called upon to raise $1,000 to help erect a monument in his honor, they readily agreed, but they were opposed to the proposed site at the foot of Fort Wagner, facing Fort Sumter. Many members of the regiment thought that this location was inappropriate: “even when peace reigns supreme, it may be desecrated by unfriendly hands.” And “why place a monument where most of those who want to view it would have to make a long pilgrimage in order to do so?” The regiment “would rather see it raised on old Massachusetts soil. The first to say a black was a man, let her have the first monument raised by black men's money, upon her good old rocks.”

24

The tribute to Colonel Shaw and the Fifty-fourth Massachusetts stands today in Boston.

Blacks served gallantly also in the Union navy. When the navy adopted a black enlistment policy as early as September 20, 1861, because of a manpower deficit, blacks, barred from service in the Union army, rushed to enlist. Of the 118,044 enlistments in the navy, 30,000 were blacks and most of them were freedmen from Massachusetts. Blacks were kept in the lowest ranks, where they were discriminated against and segregated by their commanders. None became petty officers, yet four black sailors won the Navy Medal of Honor. Joachim Pease, cited by his superior officer as having shown the utmost in courage and fortitude, is probably the best known of the four. He was the leader of the number one gun on the

Kearsarge

as well as one of the fifteen blacks on board this warship when it met the most famous Confederate raider, the

Alabama,

and engaged it in battle. Although Robert Smalls, a slave from Charleston, South Carolina, was not awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor, his escape with the Confederate

Planter

was perhaps the most dramatic incident involving a black at sea during the Civil War. Smalls waited until the vessel's officers were asleep on shore; then he and a crew of seven slaves loaded their wives and children on board and on the morning of May 13, 1862, piloted the

Planter

safely to Union lines. For his actions, Smalls was awarded an appointment in the Union navy. He went on to become one of the Reconstruction era's most prominent politicians.

FURNEY BRYANT, A FORMER SLAVE WHO ARRIVED IN NEW BERN, NORTH CAROLINA, AS A REFUGEE IN RAGS AND LATER BECAME A SOLDIER IN THE BLACK FIRST NORTH CAROLINA REGIMENT.

Courtesy of the North Carolina Division of Archives and History

John Lawson, a black from Pennsylvania, also distinguished himself in combat. He served on board the USS

Hartford,

whose job it was to take control of Mobile Bay on August 5, 1864. It was of paramount importance to the Union to knock out Mobile Bay because it was the last Confederate port on the Gulf of Mexico. There, blockade runners shipped out cotton and brought in cannon, ammunition, medicine, and other supplies needed by the rebels. Fort Morgan had to be taken out because its guns allowed the Confederate port to continue to function. As the guns of the

Hartford

fired on Fort Morgan on that somber August day, the fort's guns answered. Many of its shells found their mark, killing several sailors and severely wounding others who were tended by the surgeons below deck. One shell hit where Lawson and five other men were loading and firing. Lawson was badly injured, but refused to go below. He quickly resumed firing. Shortly thereafter, other shells began to land on target, blowing off men's arms, legs, and heads. Nevertheless, Lawson stayed at his post until the fleet had passed the fort and the minefield, sunk most of the rebel gunboats, and captured the ironclad

Tennessee.

The great battle ended by ten o'clock, and Lawson could now have his wounds dressed. The captain of the

Hartford

commended him for his bravery in action, and Lawson ultimately received the Congressional Medal of Honor.

25