Clothes, Clothes, Clothes. Music, Music, Music. Boys, Boys, Boys. (13 page)

Read Clothes, Clothes, Clothes. Music, Music, Music. Boys, Boys, Boys. Online

Authors: Viv Albertine

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Entertainment & Performing Arts

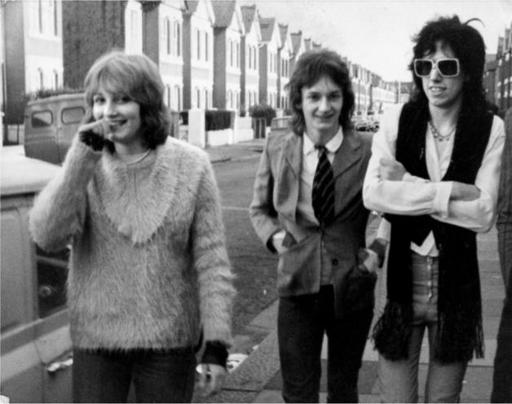

Walking down Davis Road with Keith Levene and Mick Jones, 1975

Luckily I have Keith to bolster me. He talks me round from my constant ‘Guitar Depressions’ (Keith’s term, he says he has them all the time, it happens when you stall in your learning). I play him riffs I’ve made up, humming, buzzing and fizzing like a wasp trapped in a jam jar. He says he wishes he could write things like that; he feels confined by his knowledge. Keith was very influenced by the guitarist Steve Howe from the prog-rock band Yes. He used to roadie for them when he was very young and idolised Steve. In a way Steve’s playing is being passed on to me through Keith, but it’s like that game, Chinese Whispers: by the time I get hold of it, the information has mutated and, in my hands, becomes even more mangled and distorted.

Expressing myself through the guitar is a very difficult concept to grasp. I don’t want to copy any male guitarists, I wouldn’t be true to myself if I did that. I can’t copy Lita Ford from the Runaways or the guitarist from Fanny: they don’t sound like women, they sound like men. I keep thinking, ‘What would I sound like if I was a guitar sound?’ It’s so abstract. As I experiment, I find that I like the sound of a string open, ringing away whilst I play a melody on the string next to it. It sounds like bagpipe music or Indian or Chinese, oriental and elemental. I try to play like John Cale in the Velvets, I don’t realise for ages that he’s playing violin and viola, not guitar. I want my guitar to sound like that. I like hypnotic repetition, I like the same riff played over and over again for ages. I like nursery rhymes. I love the top three trebly strings, the higher up the neck the better, and I turn the treble knob on the guitar and on the amp up full.

Then I start thinking about structure.

I don’t want to use the same old twelve-bar blues chord progressions that all rock is based on. I can’t anyway, I don’t know the formulas. (Reminds me of when I was at school and refused to learn to type, I didn’t want to rely on it. Like Buddy Holly said to his mother when she suggested he finish his exams so he’d have something to fall back on: ‘Ma, I ain’t fallin’ back.’)

Slowly I start shaping a guitar style, twisting strands together, layering then undoing and starting again, until I start to sound like me. I just wish I loved playing guitar. I thought you were supposed to love playing music, that it’s a release and a comfort, that’s what other musicians always say. For me it’s agony.

I’ve got to form a band soon, whether I can play or not. There’s Paul, sitting in the next room, trying to learn the bass, and he’s already in a band. If he can do it, then so can I.

The next step is to tell Mum I’m leaving college to make music and hopefully to join a band. We’re on the 31 bus together (sometimes I get the 31 from Camden Town to Notting Hill just for fun, it’s such a great route), chatting away on the top deck in the front seats, I’ve got my guitar between my legs. I tell her about the Pistols and the Clash and all the people I’ve met, she’s nodding and smiling, she knows I’ve always been mad about music, and is proud I’m learning an instrument. I think this is a good time to tell her my plans, I’m so enthusiastic about life: ‘Mum, I’m going to leave college and form a band!’ She bursts into tears. I hustle her off the bus and into the Chippenham pub, where I borrow some money off her and buy us half a shandy each. I bring the drinks to the table. Mum’s worked so hard to get me into college, I’m the first child to go into further education out of our whole family, she’s done cleaning jobs in the evenings after work to pay for extra books and clothes so I don’t look poor, always believed in me and my ideas, and now I’m dropping out. I can’t even play guitar yet and I’m throwing away my chance of a degree. I’ve got to convince her I know what I’m doing. ‘Look, Mum, look how I’m dressed: I look different to everyone else, I’m not like everyone else. You know how I am about music.’ She nods and manages a weak smile. Well, I’ve got to do it now, haven’t I – the last person in the world I want to hurt or let down is Mum.

30 TWIST OF FATE

1976

It’s a boiling hot Saturday afternoon, Mick and I are walking down Portobello Road, coming towards us is John Rotten, with another guy. I drop Mick’s hand immediately – don’t want to look like a drip – and we stop to have a chat. John’s hair is blond and spiky and his friend’s is black and spiky. They’re both tall and thin, they look like a couple of handsome book-ends. During the conversation, I mention I’ve bought a guitar and am going to start a band. To my amazement John’s friend says, ‘I’ll be in a band with you.’

This is an extraordinary thing for a guy to say because there are hardly any boys and girls in bands together. Mick looks uncomfortable: he likes me having a guitar but he hadn’t envisaged anything like this. If I form a band with this bloke, I’ll be in the enemy camp. The idea of us two playing together makes even the Pistols seem a bit old-fashioned. A group made up of boys and girls playing instruments is something new. I ask John’s friend what he plays. He says, ‘Saxophone.’ I arrange to meet him at Davis Road tomorrow.

As we walk away I ask Mick, ‘Who was that?’

‘Sid.’

‘What’s he like?’

‘Mate of John’s. You don’t want to get mixed up with him.’

In five minutes everything’s changed. I’m in a band with someone who looks great. I wonder why Sid wants to be in a band with me – maybe he wants to shag me, but I didn’t get that impression from him. Sid saw an opportunity and went for it. And then the rest of us thought, ‘Of course, why not?’

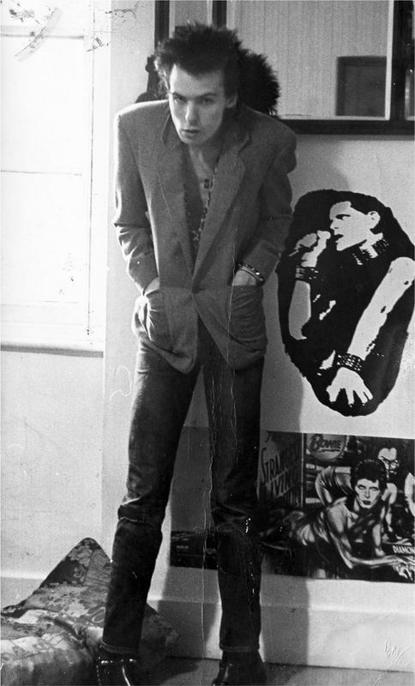

Sid acting thick

Before Sid arrives at Davis Road the next day, I put my Biba peacock chair out onto the street. We sit around the pine table in the olive-green kitchen talking about our band. For once it’s me having a band meeting – not Mick and Paul – and with someone really interesting too. Sid’s quite awkward and talks in spurts like he thinks it’s stupid to have a point of view, but he’s got to communicate, so he forces the words out. I can see it’s not that he’s unsure of his opinions, he just thinks it’s pathetic to have a strong opinion on any subject; to be intelligent means being able to see all sides. Sid likes the idea of the whole band being girls. I say I know a girl called Sarah Hall who plays a bit of bass, and Joe Strummer’s girlfriend, a Spanish girl called Paloma, who plays drums. (Paul Simonon can’t say her name so he says ‘Palmolive’ and everyone calls her that now. Paul’s not being nasty: none of us are used to foreign names, we have quite a limited existence, we’re not very worldly. Everyone we know is a Paul, Mick, Steve, John or Sue. The most exotic it gets is when someone middle-class comes along, like a Caroline or a Sebastian, or a Greek or Turkish mate at school.)

Me, Sid, Palmolive and Sarah all live in squats on different sides of London, and no one has a telephone. Sid lives with John in a council flat on the New End council estate in Hampstead, Sarah lives in Ladbroke Grove, I’m in Shepherd’s Bush, and Palmolive’s in Joe’s squat in Orsett Terrace, Westbourne Grove. The day after Sid and me have our band meeting, I get on tubes and buses and go to each person’s place to ask them if they want to be in our group. If they’re not in, I hang around for a couple of hours and keep going back and trying again. A whole day is taken up just doing that. One day for each person. I can’t get hold of Sarah so I leave her a note and just hope she’ll turn up.

Joe Strummer says we can rehearse in the basement of his squat, and all arrangements from now on are made in person at each rehearsal. There’s no way of letting anyone know if you can’t make it; that makes us turn up. No one misses a rehearsal. We’re all determined to make it happen. Not because we’re desperate to be rich and famous – well I’m not anyway – it’s just something good to do and we don’t want to let the others down.

Joe’s basement, where he used to rehearse with the 101ers, is set up with a drum kit and amps. On the first day we stand in a circle and look at each other, faces as pale and grey as mushrooms poking up out of the dirt. We decide to start with some Ramones songs: ‘Blitzkrieg Bop’ and ‘53rd and 3rd’. Sid helps me find the chords on the guitar, he’s got a good ear, but none of us can play very well and we can’t get through a song without it all falling apart. Sid’s brought a saxophone which he toots on. His hands are on the saxophone, his elbows tucked close to his body, feet and knees together, legs straight as he jumps up and down like a matchstick pinging out of a catapult. (

This catches on when he does it at gigs and is later called the Pogo

.)

31 SHOCK

1976

It’s discouraging to think how many people are shocked by honesty and how few by deceit.

Noël Coward,

Blithe Spirit

The course I was on at art school, Fashion and Textiles, was run by a sensitive, serious man and some very nice women who knitted. At the end of the first term we were set a holiday project with the brief ‘An everyday object’. I did my project about tampons. I made drawings of bloodied, used tampons swimming about in pale yellow piss down the bog. I also did life drawings of my friend Sarah Hall (bass player in my and Sid’s new band) naked in lots of different positions, with the little blue tampon string dangling from her vagina. I thought the blue string subverted the whole prurient, porn thing by showing the reality of female bodily functions, which of course you never see in sex magazines. This blatant reminder of menstruation took away the titillating aspect.

I did the project at Jane Ashley’s family cottage in Wales. I was so consumed by the work that I wouldn’t go out to the pub in the evenings with the others, I stayed behind and drew. After the holiday, I went back to college with all my drawings. The tutors were horrified. They refused to put my work – or anybody else’s work – on the wall. For the first time in the history of the course, they said, ‘Nobody’s project is going up this year.’ The whole class thought the teachers’ response was hilarious.

Another project I was working on was copying a photograph of a pile of dead bodies from a concentration camp and printing it onto T-shirts. I coloured the sky bright blue and the ground bright yellow, like sand. The image was supposed to be like a postcard, a postcard from Belsen, a camp, but not a holiday camp. (This was about the same time as Sid wrote the lyrics to ‘Belsen Was a Gas’.) I wanted to draw attention to images that had become stale and make people see them with fresh eyes. The good thing about shocking is that it clears the brain of preconceptions for a moment, and in that moment the work has a chance to cut through all the habits and learnt behaviour of the viewer and make a fresh impact, before all the conditioning crowds in again. To older people, like my mum and the parents of Jewish friends, the T-shirt was irreverent and insulting. I didn’t finish the project because I found it upsetting myself.

Sid is into subverting signs and people’s expectations too, which is why he wears a leather jacket with a swastika marked out in studs. He isn’t so stupid as to think that persecuting Jewish people is a good idea, but he does want to upset and enrage everyone and question what they’re reacting to: the symbol, or the deed? Once we hailed a cab and the driver said he wouldn’t take us because he was Jewish and offended by the swastika on Sid’s jacket. As the cabbie drove away, Sid said to me, ‘The cunt should’ve taken us and overcharged, that would’ve been a cleverer thing to do.’

My attraction to shocking goes back to the sixties: hippies and Yippies used it a lot, comic artists like Robert Crumb, the underground magazine

Oz

, Lenny Bruce, Andy Warhol. I also studied history of art at school, and learnt how Surrealists and Dadaists used shock and irrational juxtaposition. All this influences my work and I try to shock in all areas of my life, especially in my drawings and clothes. Referencing sex is an easy way to shock. I walk around in little girls’ party dresses, hems slashed and ragged, armholes torn open to make them bigger, the waistline up under my chest. My bleached blonde hair is not seductive and smooth, but matted and wild, my eyes smudged with black eyeliner. I finish it all off with fishnet tights and shocking pink patent boots from the shop Sex. I’ve crossed the line from ‘sexy wild girl just fallen out of bed’ to ‘unpredictable, dangerous, unstable girl’. Not so appealing. Pippi Longstocking meets Barbarella meets juvenile delinquent. Men look at me and they are confused, they don’t know whether they want to fuck me or kill me. This sartorial ensemble really messes with their heads. Good.