Read Coming into the Country Online

Authors: John McPhee

Coming into the Country (13 page)

We were chilled, and that was a long cold afternoon. Snake Eyes continued to move downstream like a sea anchor, and in the miserable rain we chose not to stop and build a fire. A few hours later, we embraced the fire that ended the day.

Â

Â

Â

Pourchot, after dinner in the bright evening light, began repairing the Kleppers. The hulls were so abraded, the damage so extensive, that he interrupted the job for his night's sleep and finished it after breakfast. Kleppers afloat, it is only fair to insert, are tough and sturdy boats; and, as someone pointed out, an almost identical twin of Snake Eyes in 1956 had crossed the Atlantic Ocean. “Good God!” Kauffmann said on receiving this news. But the Salmon River in low waterâwith its limestones, its dolomite, its sharp miscellaneous schistsâwas too much for the rubber-coated kayaks. Both had been leaking seriously, and as I watched Pourchot taping their hulls I could not help thinking that we would be a stone's throw from nowhere without them. He worked slowly, with fibre-glass tape, trying through applied friction to enhance the strength of the sticking.

Pourchot, after dinner in the bright evening light, began repairing the Kleppers. The hulls were so abraded, the damage so extensive, that he interrupted the job for his night's sleep and finished it after breakfast. Kleppers afloat, it is only fair to insert, are tough and sturdy boats; and, as someone pointed out, an almost identical twin of Snake Eyes in 1956 had crossed the Atlantic Ocean. “Good God!” Kauffmann said on receiving this news. But the Salmon River in low waterâwith its limestones, its dolomite, its sharp miscellaneous schistsâwas too much for the rubber-coated kayaks. Both had been leaking seriously, and as I watched Pourchot taping their hulls I could not help thinking that we would be a stone's throw from nowhere without them. He worked slowly, with fibre-glass tape, trying through applied friction to enhance the strength of the sticking.“We're up some creek,” I said, “without those boats.”

Pourchot said, “I always pack an extra day's food in case everything does not go right.”

Since he had advised bringing emergency rations, I had along a bacon bar, a can of mixed nuts, a bag of dried fruit, and half a dozen packets of M&M's. Their octane seemed low for a walk to Kiana. I had waterproof matches strewn around in various places in my pack. I asked Pourchot if he ever took along a radio, and he said no. He said there was a choice of two types and both were disadvantageous. One was an FM transmitter that was much like a walkie-talkie, but it worked only on line of sight, and, even from a ridge, would at best carry

twenty miles. Twenty miles is not an impressive radius in Alaska. Anyway, almost no one ever monitored the frequency. On the other hand, if you had a single-side-band, you could, with a properly laid-out antenna, call anywhere in Alaska. But the single-side-band was big as a breadbox, bulky, heavy (thirty pounds), and extremely expensive. So Pourchot could not be bothered with that, either. We had no axes with us, which at least reduced chances of injury. Pourchot said he had brought along a ten-dollar first-aid kit, but it had no sutures and no prescription drugs, and “a doctor would laugh at it.”

twenty miles. Twenty miles is not an impressive radius in Alaska. Anyway, almost no one ever monitored the frequency. On the other hand, if you had a single-side-band, you could, with a properly laid-out antenna, call anywhere in Alaska. But the single-side-band was big as a breadbox, bulky, heavy (thirty pounds), and extremely expensive. So Pourchot could not be bothered with that, either. We had no axes with us, which at least reduced chances of injury. Pourchot said he had brought along a ten-dollar first-aid kit, but it had no sutures and no prescription drugs, and “a doctor would laugh at it.”

He cut a short piece of tape and laid it over a particularly open break in the hull of Snake Eyes, then put a longer strip over that. “These trips are not fail-safe,” he went on. “You can get hurt and not get attention for several days. There's nothing you can do, short of staying home all the time.”

“You come to the place on its terms,” Kauffmann put in. “You assume the risk.”

“When people come to Alaska, there's a sifting and winnowing process that follows,” Pourchot said. “Some just make day trips out of Anchorage into the bush. Others go out for more than one dayâfishing or whateverâbut they stay in one place, at an established camp or lodge. After that come the hikers and canoers, and from them you get many stories of, say, the boat that breaks up and the guy who sits on the gravel bar for two weeks and walks out in five miserable days. He makes it, though. It's a rare day when somebody starves or bleeds to death. You're just not going to make a trip perfectly safe and still get the kind of trip you want. There are no what-if types out here. People who come this far have come to grips with that problem.”

Pourchot was apparently unaware that he was addressing a what-if typeâan advanced, thousand-deaths coward with oakleaf clusters. If I wanted to, I could always see disaster running with the river, dancing like a shadow, moving down the forest from tree to tree. And yet coming to grips with the problem

may have been easier for me than for the others, since all of them lived in Alaska. Risk is everywhere, but it is in some places more than others, and this was the safest place I'd been all year. I live in New Jersey, where risks to life are statistically higher than they are along an Arctic river.

may have been easier for me than for the others, since all of them lived in Alaska. Risk is everywhere, but it is in some places more than others, and this was the safest place I'd been all year. I live in New Jersey, where risks to life are statistically higher than they are along an Arctic river.

Fedeler pointed out that on the back of Alaska fishing licenses are drawings of a signal system for people in trouble who are fortunate enough to be seen by an airplane. I looked at my license. It showed a figure holding hands overhead like a referee indicating a touchdown. That meant, “Please pick me up.” A pair of chevrons, sketched on the ground, was a request for firearms and ammunition. An “I” indicated serious injury. An “F” called for food and water, and an “X” meant “Unable to proceed.”

“To get a plane to see you, a big smoky fire will help,” Fedeler said.

What had struck me most in the isolation of this wilderness was an abiding sense of paradox. In its raw, convincing emphasis on the irrelevance of the visitor, it was forcefully, importantly repellent. It was no less strongly attractiveâwith a beauty of nowhere else, composed in turning circles. If the wild land was indifferent, it gave a sense of difference. If at moments it was frightening, requiring an effort to put down the conflagrationary imagination, it also augmented the touch of life. This was not a dare with nature. This was nature.

The bottoms of the Kleppers were now trellised with tape. Pourchot was smoothing down a final end. Until recently, he had been an avocational parachutist, patterning the sky in star formation with others as he fell. He had fifty-one jumps, all of them in Colorado. But he had started waking up in the night with cold sweats, soâwith two small sons nowâhe had sold his jumping gear. With the money, he bought a white-water kayak and climbing rope. “You're kind of on your own, really. You run the risk,” he was saying. “I haven't seen any bear incidents, for example. I've never had any bear problems. I've

never carried a gun. Talk to ten people and you get ten different bear-approach theories. Some carry flares. Ed Bailey, in Fish and Wildlife, shoots pencil flares into the ground before approaching bears. They go away. Bear attacks generally occur in road-system areas anyway. Two, maybe four people die a year. Some years more than others. Rarely will a bear attack a person in a complete wilderness like this.”

never carried a gun. Talk to ten people and you get ten different bear-approach theories. Some carry flares. Ed Bailey, in Fish and Wildlife, shoots pencil flares into the ground before approaching bears. They go away. Bear attacks generally occur in road-system areas anyway. Two, maybe four people die a year. Some years more than others. Rarely will a bear attack a person in a complete wilderness like this.”

Kauffmann said, “Give a grizzly half a chance and he'll avoid you.”

Fedeler had picked cups of blueberries to mix into our breakfast pancakes. Finishing them, we prepared to go. The sun was coming through. The rain was gone. The morning grew bright and warm. Pourchot and I got into the canoe, which, for all its heavy load, felt light. Twenty minutes downriver, we had to stop for more repairs to the Kleppers, but afterward the patchwork held. With higher banks, longer pools, the river was running deeper. The sun began to blaze.

Rounding bends, we saw sculpins, a pair of great horned owls, mergansers, Taverner's geese. We saw ravens and a gray jay. Coming down a long, deep, green pool, we looked toward the riffle at the lower end and saw an approaching grizzly. He was young, possibly four years old, and not much over four hundred pounds. He crossed the river. He studied the salmon in the riffle. He did not see, hear, or smell us. Our three boats were close together, and down the light current on the flat water we drifted toward the fishing bear.

He picked up a salmon, roughly ten pounds of fish, and, holding it with one paw, he began to whirl it around his head. Apparently, he was not hungry, and this was a form of play. He played sling-the-salmon. With his claws embedded near the tail, he whirled the salmon and then tossed it high, end over end. As it fell, he scooped it up and slung it around his head again, lariat salmon, and again he tossed it into the air. He caught it and heaved it high once more. The fish flopped to the ground. The bear turned away, bored. He began to move

upstream by the edge of the river. Behind his big head his hump projected. His brown fur rippled like a field under wind. He kept coming. The breeze was behind him. He had not yet seen us. He was romping along at an easy walk. As he came closer to us, we drifted slowly toward him. The single Klepper, with John Kauffmann in it, moved up against a snagged stick and broke it off. The snap was light, but enough to stop the bear. Instantly, he was motionless and alert, remaining on his four feet and straining his eyes to see. We drifted on toward him. At last, we arrived in his focus. If we were looking at something we had rarely seen before, God help him so was he. If he was a tenth as awed as I was, he could not have moved a muscle, which he did, now, in a hurry that was not pronounced but nonetheless seemed inappropriate to his status in the situation. He crossed low ground and went up a bank toward a copse of willow. He stopped there and faced us again. Then, breaking stems to pieces, he went into the willows.

upstream by the edge of the river. Behind his big head his hump projected. His brown fur rippled like a field under wind. He kept coming. The breeze was behind him. He had not yet seen us. He was romping along at an easy walk. As he came closer to us, we drifted slowly toward him. The single Klepper, with John Kauffmann in it, moved up against a snagged stick and broke it off. The snap was light, but enough to stop the bear. Instantly, he was motionless and alert, remaining on his four feet and straining his eyes to see. We drifted on toward him. At last, we arrived in his focus. If we were looking at something we had rarely seen before, God help him so was he. If he was a tenth as awed as I was, he could not have moved a muscle, which he did, now, in a hurry that was not pronounced but nonetheless seemed inappropriate to his status in the situation. He crossed low ground and went up a bank toward a copse of willow. He stopped there and faced us again. Then, breaking stems to pieces, he went into the willows.

We drifted to the rip, and down it past the mutilated salmon. Then we came to another long flat surface, spraying up the light of the sun. My bandanna, around my head, was nearly dry. I took it off, and trailed it in the river.

WHAT THEY WERE HUNTING FOR

One morning in the Alaskan autumn, a small sharp-nosed helicopter, on its way to a rendezvous, flew south from Fairbanks with three passengers. They crossed the fast, silted water of the Tanana River and whirred along over low black-spruce land with streams too numerous for names. The ground beneath them began to rise, and they with it, until they were crossing broad benchlands and high hills increasingly jagged in configuration as they stepped up to the Alaska Range.

One morning in the Alaskan autumn, a small sharp-nosed helicopter, on its way to a rendezvous, flew south from Fairbanks with three passengers. They crossed the fast, silted water of the Tanana River and whirred along over low black-spruce land with streams too numerous for names. The ground beneath them began to rise, and they with it, until they were crossing broad benchlands and high hills increasingly jagged in configuration as they stepped up to the Alaska Range.At about the same time, another and somewhat larger group took off from Anchorage in a de Havilland Twin Otter, and this sturdy vehicle, firm as iron in the air, flew north up the valley of the Big SuâSusitna River, a big river in a land of big riversâand on up over alpine tundra that now, in the late season, was as red as wine. After moving over higher and higher hills, the plane moved in among mountains: great, upreaching things, gray on the rockface and thenâabove the five-thousand-foot contour and far on up, too high to see without pressing to the windowâcovered with fresh snow.

“Is the mountain out?” someone on the right side of the plane wanted to know. In so many mountains, there was one mountain. “Is the mountain out?”

“It surer than hell is.”

“It never looks the same.”

The mountain was a megahedronâits high white facets doming in the air. Long snow banners, extending eastward, were pluming from the ridges above twenty thousand feet.

“What would you call that mountain, Willie?”

“Denali. I'll go along with the Indians that far.”

Everyone aboard was white but Willie (William Igiagruq Hensley), of Arctic Alaska, and he said again, “Denali. What the hell did McKinley ever do?”

The Twin Otter by now was so deep in the Alaska Range that nothing could be seen but walls of mountain in a pass. Then, finally, the pass widened the way to the north. Banking over terraces and high riverine bluffsâNenana Riverâthe plane landed on gravel near a small group of buildings, a mining town. The helicopter from Fairbanks was already there. Handshakes all around. Brisk, nippy morning, right? Won't be long now. And then, in threes and fours, the group made successive flights in the small helicopterâdown the right bank of the Nenana over the broad high benchland, back and forth in loosely patterned flight. Four grizzly bearsâlarge and small, perhaps a ton or so of bearâwere grazing a meadow below, eating blueberry bushes rich with fruit. The helicopter ignored the bears. It crossed the river and flew back to the north in vectors, as if looking for something. A small lake. Then a larger lake. This was indeed a hunt, and what the people in the air were hunting for was a new capital of Alaska.

Â

Â

Â

When states move their capitals, as most of them have done at one time or another, the usual aim is to have a seat of government somewhere near the centers of geography and populationâcriteria that distinctly fail to describe Juneau. Juneau, capital of Alaska since 1900, is in the eccentric region

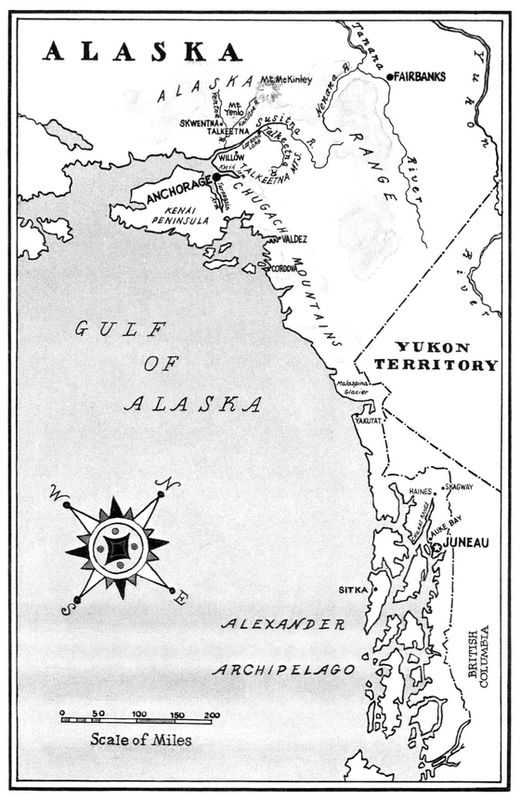

When states move their capitals, as most of them have done at one time or another, the usual aim is to have a seat of government somewhere near the centers of geography and populationâcriteria that distinctly fail to describe Juneau. Juneau, capital of Alaska since 1900, is in the eccentric regionthat Alaskans call Southeasternâa long, archipelagic claw that dangles toward Seattle and is knuckled to the main body of Alaska by a glacier the size of Rhode Island. Southeastern Alaska reaches so far east that all the land north of it is Canadian. British Columbia. Yukon Territory. Juneau is two time zones from Anchorage, from Fairbanks, from the center of the state. It is twenty-five hundred miles from the other end of Alaska. Many Alaskans do not regard Southeastern as part of Alaska but, rather, as an appendage of inconvenience, because Juneau is there. Juneau is an outportâcannot be reached, or even approached, by road. Juneau was the site of a gold strike that attracted people enough to make a town, and the town's importance increased when strikes of bonanza quantity were made in mountains to the north, along the Klondike River and other tributaries of the upper Yukon. Juneau, already a mining town, was also a way station on trips to the Klondike, and it becameâfor the duration of the gold boomâa center of Alaskan commerce.

Anchorage is the commercial center now, and roughly half of political Alaska. As a result of a petition signed by sixteen thousand, an initiative appeared on the 1974 primary ballot through which the voters could indicate a wish to move their capital. Similar initiatives in 1960 and 1962 had been defeated, perhaps in part because Alaskans elsewhere in the state did not want to see even more power concentrated in Anchorage. Anchorage, for its part, wished to yield nothing to Fairbanks. Their rivalry is intense to the point of unseemliness. So the 1974 initiative was written to exclude both citiesâthe new capital could not be within thirty miles of either oneâand in strong majority (fifty-seven per cent) the voters went for it.

The state is more or less brokeâif that term can be used to describe a budget that regularly expends a great deal more than it ingests. For this reason, it might seem an act of bravado to contemplate building anything at all, let alone a new capital city. Bravado, on the other hand, is a synonym for Alaska. A high proportion of the white people who have tried to make

their way in Alaska have lived from boom to boom. The first boom was in fur, and then came gold, followed by war, and now oil. How could it matter that the treasury was atilt when the Alyeska Pipeline Service Company was moving toward completion of a tube that would draw so much oil out of the north of Alaska that the state government alone would collect in royalties as much as three and a half million dollars a day? Some Alaskans were already spending the money. Others were dreaming of ways to spend it. One of the dreams was of a new capital, in a wild setting, preferably within sight of the summits of North America's highest massif.

their way in Alaska have lived from boom to boom. The first boom was in fur, and then came gold, followed by war, and now oil. How could it matter that the treasury was atilt when the Alyeska Pipeline Service Company was moving toward completion of a tube that would draw so much oil out of the north of Alaska that the state government alone would collect in royalties as much as three and a half million dollars a day? Some Alaskans were already spending the money. Others were dreaming of ways to spend it. One of the dreams was of a new capital, in a wild setting, preferably within sight of the summits of North America's highest massif.

Following the terms of the initiative, the governor of Alaska appointed a Capital Site Selection Committee, most of whose nine members had beenâlike the governor himselfâopponents of the initiative. One might think that only Gilbert and Sullivan could work out the story from there. The committee, thoughârepresenting a geographical spread of the state, including Southeasternâhad taken up its work with a seriousness Alaskan in grandeur, and would spend well over a million dollars to narrow its choices down.

Â

Â

Â

The move to move the capital has “bestirred the community,” as one Alaska senator has put it, and from the community has come a chorus of comment. The dialogue assembled here contains voices from Seward, Sitka, Fort Yukon, Kotzebue, Fairbanks, Juneau, Anchorage.

The move to move the capital has “bestirred the community,” as one Alaska senator has put it, and from the community has come a chorus of comment. The dialogue assembled here contains voices from Seward, Sitka, Fort Yukon, Kotzebue, Fairbanks, Juneau, Anchorage.“Despite the terms of the initiative, Anchorage is the logical place for the capital. The move would cost the least, and Anchorage would serve best. Anchorage should be the capital.”

“There are more state-government employees in Anchorage now than there are in Juneau.”

“Everyone is afraid of, and is envious of, Anchorage.”

“Anchorage has got enough.”

“People don't want the Anchorage scourge to spread.”

“The initiative was a vendetta.”

“The capital move started with people in Anchorage who thought they were getting screwed by the legislature in Juneau.”

“Make no mistake. Anchorage wants the capital in Anchorage and will somehow get it.”

“Anchorage works hard to get things from other towns. It has from the start. When Anchorage was just a few people in tents, they tried to take the headquarters of the railroad from Seward and the U.S. District Court from Valdez. In both instances, they succeeded. Recently, they have tried hard to take the university from Fairbanks. They have part of it already. They wooed the U.S. land office away from Juneau. âProud' is a word still used here in Alaskaâbut not about Anchorage.”

A single voice can be particularly audible in Alaska, because there are so few people. Much is made of Alaska's great size. It is worth remembering, as well, how small Alaska isâa handful of people clinging to a subcontinent. There are nearly twice as many people in the District of Columbia as there are in the State of Alaska. In ten square miles of the eastern state I live in are more people than there are in the five hundred and eighty-six thousand square miles of Alaska.

“The capital must be a new city.”

“Pipeline or no pipeline, the state would go broke buying land in Anchorage. On top of that, because everybody in Alaska hates Anchorage it is politically expedient to put the capital in a new place, an undeveloped place.”

“The land out there is of no great value. It's just wilderness, standing there.”

Â

Â

Â

The committee's flight through the mountains that morning appeared to be, as much as anything else, a gesture of courtesy

The committee's flight through the mountains that morning appeared to be, as much as anything else, a gesture of courtesyto Fairbanks,

de facto

capital of the terrain that is called the Interior. Fairbanks is the pivot from which travellers fan out to the northâthe usual departure point for Arctic Alaska, and the departure point, as well, for mail planes and bush craft that serve the Interior villages. A look at a map would suggest a site near Fairbanks as an obvious capital for the state as a whole, because of Fairbanks' position near the center of the Alaskan mainland. There are drawbacks, however, in climate. The Interior is so named because it lies between the Brooks Range, which traverses the far north, and the Alaska Range, which is the climax of the mountain chain that comes up the Pacific coast and then bends across south-central Alaska to indicate the Aleutians. The Interior is the hottest region of Alaska. It is also the coldest. Temperatures there can go into the nineties in summer and into the minus-seventies in winter, and at times of deep cold large areas of the Interior will be palled with ice fog. Fairbanks has more motor vehicles per capita than does Los Angeles, and as the cars toot and tap bumpers on the long crawls through the ice fog the warm gases of their exhaust plumes seem to stick in the air close around themâan especially pernicious, carcinogenic subarctic variety of smog. This experience would suggestâtoo late to help Fairbanksâthat it might be imprudent to plan deliberately to attract numerous vehicles to a single site in the Interior.

Other books

Over the Moon by David Essex

The Lost Witch by David Tysdale

The Heiress Effect by Milan, Courtney

Quintic by V. P. Trick

Demon's Caress: Demon Heat, Book 1 by Crystal Jordan

Indoor Gardening by Will Cook

Almost Innocent by Jane Feather

The Spectator Bird by Wallace Stegner

Mail Order Minx: Fountain of Love (Brides of Beckham) by Osbourne, Kirsten

A Clockwork Christmas Angel by J. W. Stacks