Complete Works of Emile Zola (1844 page)

Read Complete Works of Emile Zola Online

Authors: Émile Zola

An hour afterwards they found Micoulin’s mutilated body under the stones. Toine, almost crazy, related how he had almost been carried away himself; and everybody declared that it was wrong to carry a stream along the top of the cliff, on account of the infiltrations.

The old wife wept a great deal. As for Naïs, she followed her father to the cemetery with tearless eyes On the day after the catastrophe, Madame Rostand had insisted upon returning to Aix. Frédéric was very pleased to leave, for the terrible drama had disturbed his peace of mind; and, moreover, in his opinion, peasant, girls with all their good looks were not equal to their town-bred sisters. He resumed his old mode of life. His mother, touched by his attentiveness to her at La Blancarde, gave him more liberty, so that he passed a very pleasant winter, and fondly hoped that his life would always thus glide smoothly away.

Monsieur Rostand had to go to La Blancarde at Easter, and wished his son to accompany him; but the young man made various excuses. When the lawyer came back, he said the next morning at breakfast: ‘Oh! by the way, Naïs is going to be married.’

‘Never!’ cried Frédéric in amazement.

‘And you’d never guess to whom,’ continued Monsieur Rostand. ‘She gave me such good reasons, however.’

The fact was Naïs was marrying Toine. In that way nothing would be changed at La Blancarde. Toine would still manage the property, as he had done since Micoulin’s death.

The young man listened with an awkward smile. Presently he expressed the opinion that the arrangement was the best one possible for everybody concerned.

‘Naïs has grown very old and plain,’ continued Monsieur Rostand. ‘I didn’t know her again. It is astonishing how quickly girls age on the coast; and she used to be quite pretty, too.’

‘Yes, a feast of sunlight,’ said Frédéric composedly, and he quietly went on eating his cutlet.

THE END

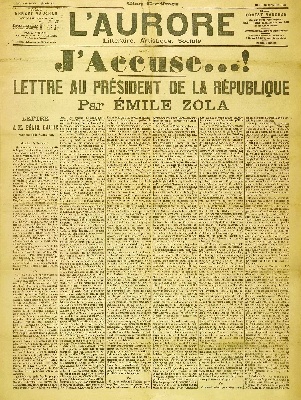

J’Accuse !

Now regarded as one of Zola’s noblest achievements,

J’Accuse

was an open letter he published on January 13, 1898, in the newspaper

L’Aurore

. The letter was printed on the front page, causing a sensation internationally as well as in France. In the letter, the author addresses President Félix Faure, accusing the government of anti-Semitism and the unlawful jailing of Alfred Dreyfus, a French Army General Staff officer sentenced to penal servitude for life for espionage. Throughout the letter, Zola identifies judicial errors and the alarming lack of serious evidence in the charging of Dreyfus. The publication of the letter resulted in Zola being prosecuted and found guilty of libel on 23 February 1898. To avoid imprisonment, he fled to England, returning home in the following year.

Alfred Dreyfus came from prosperous Jewish family and served as an artillery captain for the General Staff of France. However, Dreyfus was suspected of providing secret military information to the German government. A French spy by the name of Madame Bastian, working at the German Embassy, was the cause of the investigation. She routinely searched wastebaskets and mailboxes at the German Embassy, where she found a suspicious document in 1894, delivering it at once to the French military counterintelligence. The document had been torn into six pieces and found in the office of Maximilian von Schwartzkoppen, the German military attaché. When the document was investigated, Dreyfus was convicted largely on the basis of testimony by professional handwriting experts, who claimed that the lack of resemblance between Dreyfus’ writing and that of the document was proof of a ‘self-forgery, and they went so far as to provide a detailed diagram to demonstrate their theory. There were also assertions from military officers that provided confidential evidence. Dreyfus was found guilty of treason in a secret military court-martial, during which he was denied the right to examine the evidence against him. The Army stripped him of his rank in a humiliating ceremony and dispatched him to Devil’s Island, a penal colony located off the coast of French Guiana in South America.

Due to the prevailing anti-Semitism in France at the time, there were few people outside of his family that defended Dreyfus. With the publication of

J’Accuse!

Dreyfus’ fortunes turned, gaining the attention of the international press and the pity of the French public. In 1899, Dreyfus returned to France for a retrial, but although found guilty again, he was pardoned. In 1906, Dreyfus appealed his case once more and was eventually fully exonerated, being awarded the Cross of the Légion d’honneur and declared “a soldier who has endured an unparalleled martyrdom.”

As a result of the popularity of Zola’s letter, the term ‘J’Accuse!’ has since become a common expression of outrage and accusation against a powerful wrongdoer.

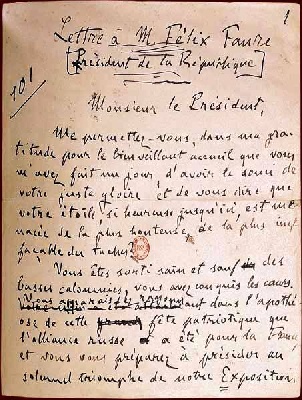

The first page of the manuscript, 1898

How the letter first appeared

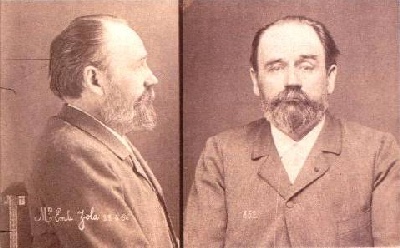

The police photographs taken of Zola at the time of his trial

Alfred Dreyfus

I ACCUSE...!

Letter to Mr. Félix Faure, President of the Republic

Mr. President,

Would you allow me, in my gratitude for the benevolent reception that you gave me one day, to draw the attention of your rightful glory and to tell you that your star, so happy until now, is threatened by the most shameful and most ineffaceable of blemishes?

You have passed healthy and safe through base calumnies; you have conquered hearts. You appear radiant in the apotheosis of this patriotic festival that the Russian alliance was for France, and you prepare to preside over the solemn triumph of our World Fair, which will crown our great century of work, truth and freedom. But what a spot of mud on your name — I was going to say on your reign — is this abominable Dreyfus affair! A council of war, under order, has just dared to acquit Esterhazy, a great blow to all truth, all justice. And it is finished, France has this stain on her cheek, History will write that it was under your presidency that such a social crime could be committed.

Since they dared, I too will dare. The truth I will say, because I promised to say it, if justice, regularly seized, did not do it, full and whole. My duty is to speak, I do not want to be an accomplice. My nights would be haunted by the specter of innocence that suffer there, through the most dreadful of tortures, for a crime it did not commit.

And it is to you, Mr. President, that I will proclaim it, this truth, with all the force of the revulsion of an honest man. For your honor, I am convinced that you are unaware of it. And with whom will I thus denounce the criminal foundation of these guilty truths, if not with you, the first magistrate of the country?

* * *

First, the truth about the lawsuit and the judgment of Dreyfus.

A nefarious man carried it all out, did everything: Lieutenant Colonel Du Paty de Clam, at that time only a Commandant. He is the entirety of the Dreyfus business; it will be known only when one honest investigation clearly establishes his acts and responsibilities. He seems a most complicated and hazy spirit, haunting romantic intrigues, caught up in serialized stories, stolen papers, anonymous letters, appointments in deserted places, mysterious women who sell condemning evidences at night. It is he who imagined dictating the Dreyfus memo; it is he who dreamed to study it in an entirely hidden way, under ice; it is him whom commander Forzinetti describes to us as armed with a dark lantern, wanting to approach the sleeping defendant, to flood his face abruptly with light and to thus surprise his crime, in the agitation of being roused. And I need hardly say that that what one seeks, one will find. I declare simply that commander Du Paty de Clam, charged to investigate the Dreyfus business as a legal officer, is, in date and in responsibility, the first culprit in the appalling miscarriage of justice committed.

The memo was for some time already in the hands of Colonel Sandherr, director of the office of information, who has since died of general paresis. “Escapes” took place, papers disappeared, as they still do today; the author of the memo was sought, when ahead of time one was made aware, little by little, that this author could be only an officer of the High Comman and an artillery officer: a doubly glaring error, showing with which superficial spirit this affair had been studied, because a reasoned examination shows that it could only be a question of an officer of troops. Thus searching the house, examining writings, it was like a family matter, a traitor to be surprised in the same offices, in order to expel him. And, while I don’t want to retell a partly known history here, Commander Paty de Clam enters the scene, as soon as first suspicion falls upon Dreyfus. From this moment, it is he who invented Dreyfus, the affair becomes that affair, made actively to confuse the traitor, to bring him to a full confession. There is the Minister of War, General Mercier, whose intelligence seems poor; there are the head of the High Command, General De Boisdeffre, who appears to have yielded to his clerical passion, and the assistant manager of the High Command, General Gonse, whose conscience could put up with many things. But, at the bottom, there is initially only Commander Du Paty de Clam, who carries them all out, who hypnotizes them, because he deals also with spiritism, with occultism, conversing with spirits. One could not conceive of the experiments to which he subjected unhappy Dreyfus, the traps into which he wanted to make him fall, the insane investigations, monstrous imaginations, a whole torturing insanity.