Copyright Unbalanced: From Incentive to Excess (13 page)

Read Copyright Unbalanced: From Incentive to Excess Online

Authors: Christina Mulligan,David G. Post,Patrick Ruffini ,Reihan Salam,Tom W. Bell,Eli Dourado,Timothy B. Lee

On the other hand, in their exceptionalist zeal for the information economy, a number of technically minded commentators have embraced the opposite extreme. They argue that all forms of access control are doomed. At root, proponents of this view also fail to properly consider the costs and benefits for all populations. It’s true that nearly any workable form of access control, whether it be encryption-based digital rights management or a registration-based paywall, is vulnerable to those truly determined to overcome it. But not everyone has such strong determination to get content for free. Many ordinary consumers would rather spend a few bucks than invest the time and energy to circumvent access controls. To them, this time and energy, however small, is a cost of accessing the content, whereas to many playful nerds, it can be a fun challenge to try to find a way around the access control.

There may also be other benefits bundled with the content. A number of users who routinely pirate movies pay to see some of them in the theater; it is hard to match the experience of the big screen. Video game makers can bundle leaderboards and social features with versions of their games that authenticate online. Perhaps the biggest benefit that some users get from paying for content is a good feeling associated with supporting a content producer. The super-rich have patronized artists and thinkers for centuries. Ordinary consumers may share a motivation to contribute to the production of more content, or even just to affiliate with their favorite producers by patronizing them in this small way.

The bottom line is that both of the extreme viewpoints about the nature of the content industry are wrong. A moderate position is more nearly correct. The purpose of access controls should not be to try to exclude all nonpayers, but that does not mean that they have no role. Rather, the role of access controls should increasingly be to induce those users who are willing to pay for access to do so, and to pay no mind to those users who are willing to invest some effort in circumventing them.

The

New York Times

may or may not have thought through the paywall in exactly these terms, but nevertheless, the company’s strategy is consistent with the analysis above. This example is important because the newspaper industry is in the vanguard with respect to changes wrought by the Internet; news was one of the first popular uses of the web. In particular, news is one of the first content production domains that the Internet has radically democratized. The up-front costs associated with starting a news website are miniscule compared to those necessary to start a newspaper. This has led to a staggering amount of competition in the market for online news and opinion journalism. While hypercompetition has been bad for incumbent profits, consumers have benefited from greater availability and diversity of content.

Disruption has been slower in other traditional content industries like music and film. But we can be optimistic that disintermediation of these industries is still coming. The tools needed to compete with the record labels have only emerged in the last decade, as distribution platforms for digital music have matured and high-quality audio recording and editing software has dropped in price. Bands are increasingly marketing their own music and tours directly to fans; the decline in the importance of labels is underway. Because of the greater costs associated with producing and marketing movies, the film industry is lagging behind these trends. But what reason is there to doubt that the inexorable march of digital democratization will stop before it disrupts the film industry? As technology improves, it too will become more like the newspaper industry.

If these changes are indeed underway, then it seems reasonable to predict that the slower-changing content industries will ultimately adopt content enforcement strategies that are similar to those used by the industries that have experienced more thoroughgoing change. Some of the details may differ; for example, because news sites can rely more heavily on advertising than other content industries can, they have an incentive to use more porous access control methods. But this is merely a matter of degree. The basic strategy of price discriminating by using access controls to get consumers to self-select into paid and unpriced segments is sound. Consider the hit TV show

Game of Thrones

. Millions of people pirated the show, more than watched it through legitimate channels.

10

Although HBO could have sued infringing users, it did very little to combat this piracy. Instead, HBO basically accepted the piracy because most nonpaying users would not otherwise subscribe to HBO, and because the pirates helped create a stronger buzz for the show, which helped it succeed. Furthermore, the existence of pirated copies of the show did not eliminate the incentive to subscribe, at least for those customers who valued watching the show the day it first aired, in uncompressed high definition, with a minimum of fuss.

As an example of weak copyright enforcement, the case of the

New York Times

paywall also gives some indication of what a world with weaker legal copyright protection would look like. Contrary to what some of the pessimists say, we would still enjoy new content, but content industries that have been slow to adapt would need to change. They might have to explore new business models or embrace creative ways to encourage customers to pay for content. In this important sense, the music and movie industries would have to become more like the news industry.

Of course, this is exactly what a lot of content producers fear. Newspapers have struggled during the transition to the Internet era, and profits have suffered. But the point of copyright is not to protect the profits of content producers; it is to ensure that content production flourishes. On this score, the news industry has never been healthier. We have more options for journalistic content than ever before. There are news sites that are both general and niche, serious and sassy, demure and sensationalist, shortform and longform. One of the biggest problems that Internet users face is coming up with satisfactory

filtering

mechanisms for their online news, there is so much of it. Meanwhile, news sites are finding creative ways to earn enough money to stay in business—in some cases, just barely. And that’s just fine.

This chapter has argued that weak access controls, like the

New York Times’

porous paywall, represent the future of content monetization. Despite two competing misconceptions about the role of access controls, it is likely that we will see more content producers adopt similar strategies. It is worth asking, therefore, how intellectual property law needs to change to match the reality of how content will be funded and distributed in the 21st century.

First, the law needs to abandon the criminalization of copyright infringement. In a world where content producers are not substantially harmed and possibly even benefit from some level of circumvention of their access controls, it does not make sense to criminalize those who circumvent access controls. Laws like the Digital Millennium Copyright Act make users who disable the

Times’

paywall into criminals. In fact, it is a good thing that the

New York Times

has slightly changed the way its paywall operates in the last year, because otherwise the code at the beginning of this chapter would be illegal to distribute under the DMCA, and those involved in producing and selling this book could face criminal charges. Given that the

Times

spent extra money to make sure that its paywall was especially porous, it seems absurd to criminalize the act of circumventing it. Furthermore, the criminalization of piracy mostly protects those content industries that have been the slowest to adapt to the Internet era. If we want adjustment to happen rapidly, we need to stop subsidizing old business models.

Second, copyright law should focus on commercial infringement only. The

Times

does not enforce its copyright against ordinary “infringing” users, but it derives some benefit from the fact that its competitors cannot engage in wholesale appropriation of its content. The law can differentiate between those who redistribute copyrighted content for profit without permission and those who simply consume it on a noncommercial basis. The benefits of the latter kind of enforcement are low or—as in the case of the

Times’

paywall—negative, and the costs are high. In contrast, enforcement against commercial infringement plausibly has high benefits. It is also less costly to enforce copyrights against commercial infringement, if only because such redistribution is predicated on consumers knowing where to go to get the infringing content. Most likely, this involves some sort of open and notorious behavior on the part of the infringer, such as advertising or maintaining a home page.

Finally, we need to embrace a stronger role for informal norms than for formal law to ensure that content producers are compensated. A number of people subscribe to the

Times

because it makes them feel good to do so. They may know several of the tricks that people use to penetrate the paywall, but they subscribe anyway. The spirit of patronage is alive and well, but nothing is more likely to destroy it than the feeling that content producers and consumers are on different sides, which is exactly what copyright enforcement engenders. Consequently, we should begin to reevaluate whether formal copyright enforcement is necessary at all. The evidence that it is necessary is surprisingly meager, and there is innovation in several domains, such as joke telling, recipes, sports moves, and fashion, in which copyright does not apply.

11

While customers of the

Times

may not all be conservatives or libertarians, their patronage of content they enjoy is evidence that we don’t need the state to promote the progress of science and the useful arts.

NOTES

1

. Brett Pulley, “

New York Times

Fixes Paywall Flaws to Balance Free versus Paid on the Web,”

Bloomberg.com

, January 28, 2011,

http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2011-01-28/new-york-times-fixes-paywall-glitches-to-balance-free-vs-paid-on-the-web.html

.

2

. Staci D. Kramer, “

New York Times

Paywall Cost: More Like $25 Million,”

paidContent

, April 7, 2011,

http://paidcontent.org/2011/04/07/419-new-york-times-paywall-cost-more-like-25-million

/.

3

. Mike Masnick, “It Took the

NY Times

14 Months and $40 Million Dollars to Build the World’s Stupidest Paywall?,”

Techdirt

(blog), March 17, 2011,

http://www.techdirt.com/articles/20110317/10393913530/it-took-ny-times-14-months-40-million-dollars-to-build-worlds-stupidest-paywall.shtml

.

4

. This example is not perfectly general. It is

possible

to construct examples where price discrimination reduces total welfare. It is also

easy

to construct examples where total welfare increases, but consumer welfare decreases. In general, where price discrimination causes total output to increase and does not itself impose many costs, price discrimination is almost always welfare-improving.

5

. Felix Salmon, “The NYT Paywall Arrives,” Reuters (blog), March 17, 2011,

http://blogs.reuters.com/felix-salmon/2011/03/17/the-nyt-paywall-arrives

/.

6

. New York Times Company, “The New York Times Company Reports 2012 First-Quarter Results,” press release, April 19, 2012,

http://www.nytco.com/pdf/1Q_2012_Earnings.pdf

; New York Times Company, “The New York Times Company Reports 2012 Second-Quarter Results,” press release, July 26, 2012,

http://www.nytco.com/pdf/2Q_2012_Earnings.pdf

. This figure includes digital subscribers to the

International Herald Tribune

, which is owned by the New York Times Company and features some of the same content. The New York Times Company does not break down the numbers further.

7

. New York Times Company, “The New York Times Company Reports 2011 First-Quarter Results,” press release, April 21, 2011,

http://www.nytco.com/pdf/1Q_2011_Earnings.pdf

.

8

. New York Times Company, “The New York Times Company Reports 2012 Second-Quarter Results.”

9

. Felix Salmon, “The NYT Paywall Is Working,” Reuters (blog), July 26, 2011,

http://blogs.reuters.com/felix-salmon/2011/07/26/the-nyt-paywall-is-working

/.

10

. Casey Chan, “More People Pirate

Game of Thrones

Than Watch

Game of Thrones

on HBO,”

Gizmodo

(blog), June 8, 2012,

http://gizmodo.com/5916885/more-people-pirate-game-of-thrones-than-watch-game-of-thrones-on-hbo

.

11

. Kal Raustiala and Christopher Jon Sprigman,

The Knockoff Economy: How Imitation Sparks Innovation

(New York: Oxford University Press, 2012).

Five Reforms for Copyright

Tom W. Bell

O

N NOVEMBER

28, 2009, police arrested a 22-year-old Chicago woman named Samantha Tumpach, jailed her for two nights, and charged her with “criminal use of a motion picture exhibition”—a felony offense punishable with up to three years in prison. Her crime? She had captured two brief clips of

The Twilight Saga: New Moon

while recording her family’s surprise birthday celebration for her sister, who had come to the theater to watch the film.

1

Tumpach copied under four minutes of the movie in total and obviously had no intention of making a bootleg for resale. “You can hear me talking the whole time,” she explained.

2

Officials eventually dropped the charges, but the damage had been done. Tumpach brought suit for malicious prosecution, intentional infliction of emotional distress, negligence, and defamation.

3

Her complaint did not, however, name the ultimate cause of her distress: a copyright regime that has grown too big and too powerful.

How should we reform copyright? By treating it the same way we should treat federal farm subsidies, Medicare, or any one of a number of big government programs. If you doubt whether politicians and bureaucrats can do a good job of regulating agricultural production or health care, you should also doubt the efficacy of the Copyright Act, through which the federal government comprehensively regulates markets in original books, movies, plays, photographs, emails, videos, computer programs, and other expressive works. Copyright represents at best a necessary evil. More likely, it offers us a Faustian bargain of dubious propriety. We can best improve copyright by limiting its power, repairing its foundations, and opening up ways to escape it entirely.

That is not the typical approach to copyright reform, concededly. On one hand, most policy wonks regard copyright as a well-intentioned but clunky government program that they might save with only a bit of tinkering around the edges (though what copyright needs saving from—whether industry lobbyists

4

or rampaging pirates

5

—depends on which analyst you ask). On the other hand, a few philosophically minded commentators decry copyright as an unjustifiable imposition on individual liberties and, as such, deserving immediate abolition.

6

You would not end slavery in steps, would you?

7

So too, these critics ask of copyright.

This chapter offers a third approach to copyright reform, one that pays due respect to copyright’s honorable origins and potential benefits but that warily regards it as a growing infringement on individual liberty. The reforms described here constrain copyright within its proper limits while encouraging us to explore, cautiously and incrementally, how far we can go toward a copyright-free world. Below follow the details of five specific reforms:

1. Reinstate the Founders’ Copyright Act,

2. Withdraw the US from the Berne Convention,

3. Develop misuse doctrine into an escape from copyright,

4. Focus copyright policy on consumers’ costs, not producers’ profits, and

5. Reconceive “IP” as “Intellectual

Privilege

.”

Before fleshing out these proposed reforms, however, it bears asking whether copyright needs fixing in the first place. It does—but not for the reasons that you might at first expect. The next section explains.

Is copyright in crisis? It has critics, of course, but nobody really knows how bad things have gotten. Despite prominent claims that the copyright law strikes a “delicate balance” between public and private rights, we cannot measure its success or failure with anything like precision. News stories occasionally suggest that copyright law has grown too powerful, as when Samantha Tumpach was arrested for incidentally recording bits of

Twilight

, but that provides merely anecdotal evidence.

Policy wonks demand better, but copyright’s breadth, intangibility, and heterogeneity will leave them frustrated. The problem arises not merely from the manifold variables at stake—words published, poems read, lines coded, scenes shot—but from the incommensurable values affected by copyright. We should reform copyright not in pursuit of policy perfection, an impossible dream, but in defense of freedom.

At root, copyright recalls a proverbial deal with the devil. In pursuit of “the Progress of Science and useful Arts,” the Constitution empowers Congress to “secur[e] for limited Times to Authors … the exclusive Right to their … Writings.”

8

Lawmakers responded to that invitation by passing the Copyright Act, a federal statute that now comprehensively regulates the production and distribution of books, plays, movies, programs, and other fixed expressive works. Did the public come out ahead under that Faustian bargain? We might ask the same question of federal regulation of agricultural subsidies, health care, home mortgages, or education. Different analysts will answer with different numbers, all of them mere approximations and none of it sufficient to decide the choice between comfortable servitude and daring independence.

Copyright, as a legal regime, is not in crisis; it grows and thrives. The first Copyright Act, passed in 1790 by many of the same people who founded the United States, includes just seven sections and 1,308 words and fills fewer than two pages.

9

Since then the US Copyright Office has taken root in the Library of Congress and grown like a vast canopy of vines over copyright.

Circular 92

, the office’s most recent compendium of the laws under its purview, weighs in at more than 350 pages and 150,000 words.

10

Separately from those statutory provisions, the Copyright Office’s own detailed and voluminous regulations run (or rather plod) to more than 170 sections and uncounted words.

11

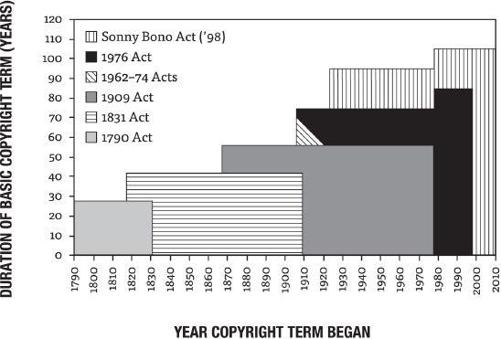

As the graph opposite demonstrates, the term of US copyrights has steadily expanded over the years.

12

Other comparisons between the Founders’ law and the present law follow in the next section, which describes the good old days of the 1790 Copyright Act. It all goes to show that we should not fear for copyright; we should fear for our liberties.

The five copyright reforms described below do not come with any guarantee of net social welfare gains. They guarantee only increased freedom. Although that will doubtless suffice for some readers, those more accustomed to cost–benefit analyses should note that copyright, as a scheme for federally regulating markets in expressive works, probably falls far short of optimal efficiency. Lawmakers have already tried massive doses of statism. Their recent innovations include retroactively extending copyright terms, controlling the design of consumer electronics, authorizing ex parte seizures of domain names, and creating a new “IP Czar.”

13

We can surely do better than more of the same. Quantitative certainty will continue to elude us and minor tweaks to the status quo will not suffice. Instead, we need to pursue a new direction in copyright reform: toward freedom.

You find yourself trapped between a lumbering but hungry bear and a deep, narrow chasm. After quickly calculating the downsides of wrestling your way out of trouble, you decide to jump across to safety. You need a running start first, though, so you back up a few steps. Only then do you run to the edge and leap to your freedom. So, too, with copyright reform: To make our way forward, we must first step back.

Trend of Copyright Duration in US Law

US copyright law begins in the Constitution, ratified in 1789, and the 1790 Copyright Act that followed quickly thereafter.

14

Beyond the words themselves, which empower Congress to “promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors … the exclusive Right to their … Writings,” we have little evidence about what the Constitution means of copyright.

15

Notes from the Philadelphia Convention hardly mention the topic, nor did copyright get much analysis in the contemporary press or ratification debates.

16

The most substantive public comment came from James Madison, who spent four brief sentences in

The Federalist

No. 43 defending the proposed copyright power (and who misrepresented copyright’s status in the common law in the process).

17

Our best evidence about what the founding generation thought about the constitutional limits to copyright thus comes from what they

did

almost immediately following ratification: they passed the 1790 Copyright Act. To judge from that statute, they did not think copyright deserved very long or broad protections. As mentioned earlier in this chapter the 1790 act offered a copyright term of only 14 years with the option to renew for another 14.

18

By way of comparison, the basic term in the present act runs for the author’s life plus 70 years.

19

The 1790 act afforded copyright holders but few remedies—only statutory damages and the destruction of infringing works.

20

Remedies in the current act include destruction of infringing copies and devices used in infringement,

21

statutory damages or actual damages and unjust profits,

22

costs and attorneys’ fees,

23

bars on the importation of infringing articles,

24

the power to subpoena digital service providers to disclose the identity of alleged infringers,

25

and criminal sanctions including fines and imprisonment.

26

Most surprisingly, the 1790 act covered only maps, charts, and books.

27

The present act, in contrast, covers all kinds of graphic and literary works, as well as songs, plays, dances, sculptures, movies, sound recordings, architectural works, computer programs, and indeed any original fixed expression of authorship, no matter what its form.

28

Under current law, even a grocery list can win a copyright. Although some modern modes of expression might have surprised the Founders, they certainly knew about the charms of songs, plays, dances, sculptures, and architectural works. Why did they not include those works in the scope of the 1790 act?

The Founders seem to have taken very seriously the constitutional mandate that copyright promote “Science and the useful Arts”—words that, then as now, most plainly refer not to mere pretty fripperies but rather to useful, even technical works. The 1790 act’s concern for maps and charts plainly reflects that tough-minded and characteristically American philosophy. So does the act’s concern for books, which the Founders probably considered to be utilitarian tools more than amusing diversions. Novels had not yet risen to prominence in that early literary era, after all; the first American novel, William Hill Brown’s

The Power of Sympathy

, appeared only a year before passage of the 1790 act (and even its ad copy promised the practical goal of exposing “the fatal consequences of seduction”).

29

Judging from the titles in libraries and on sale, fiction made up only a small portion of the books available in late 18th-century America.

30

The Founders evidently aimed to have copyright serve the practical needs of a growing nation rather than the creative urges of songwriters, painters, sculptors, and other artists.

Whether the narrow scope of the 1790 act came from timidity, considerations of public policy, or respect for constitutional limits we cannot say for certain. The historical context and legislative history of the 1790 act shows no consideration that music, pictures, dances, plays, sculptures, or the like might qualify as “Writings” by “Authors” liable to “promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts,” as the Constitution specifies.

31

Regardless, it was not for ignorance or want of love that the Founders denied copyrights to the pure arts.