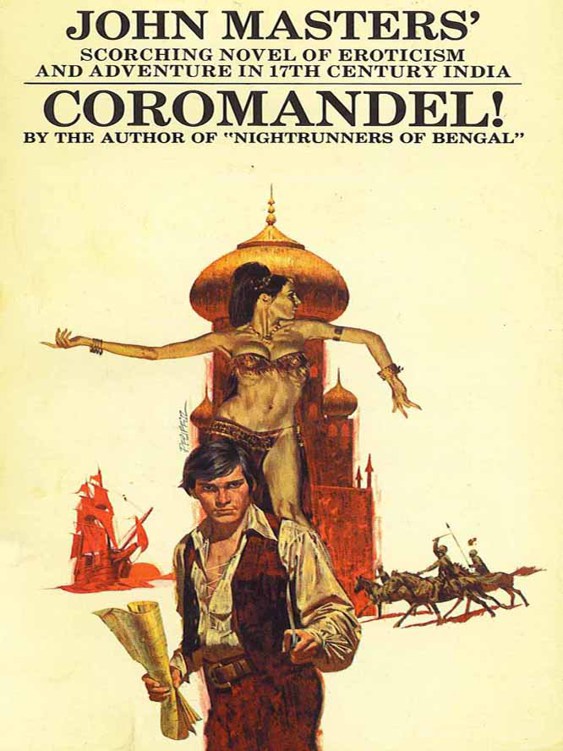

Coromandel!

John Masters

First published by Michael Joseph Ltd 1955

Copyright © John Masters 1955

For SUSAN

The girl leaned out of the casement, the leaded panes and all her face dark in the shadow of the overhanging thatch. The clock in the church tower struck twelve.

The cracked notes dropped slowly, one by one, into the moon-lit well of the green, and ran about the lanes of the village and crept down in softer echoes from the slope of the Plain beyond. The churchyard lay below the girl’s window. The gravestones shone silently with the pale fire of the night, and the shadows of them knelt in square blocks, like patient mourners, on the humps of the graves. The wind moved warm from the valley to the Plain, and summer was nearly gone.

The girl sighed and rested her weight heavily on her elbows and waited. She was naked, warm, and kindly. She heard nothing, and thought of nothing but her waiting, although the wind made music in the thatch so close above her head.

The young man moved slowly under the edge of the Plain, in the shadow of the last hedge. He moved as though watchers lay in wait for him in the moonlight. He paused at a tussock of grass, and again in the shadow of a group of elms, and looked ahead, to right and left, and behind, then he moved on. He heard music in the silence and saw men where he knew there were none; so he had forgotten the girl and her waiting.

The vale dipped down to his right. There, lying in the moon-light, the wheat was cut and the fields were bare and the orchards heavy. He was moving along the border between the cultivation and the Plain. He liked best to prowl that line, especially at night, because the fields made him think of people, but the Plain was empty and full of lonely music, and he needed both to build substance for his dreams.

He stopped and looked about him with a frown. It was good to summon phantoms from his mind to go beside him and so make the familiar strange. But he must not do that all the time, or soon he would not be able to tell which things he had made and which God had made. In truth this was only one night of a thousand he had known like it, only a summer night. The owl screeched from the firs in Bellman’s Hollow above him, but that was its habit. The wind stirred the grass of the Plain as it had always done. The farm slept behind him, and the village in front of him slept, and only one light shone in the vale, far and yellow among the woods, and he knew that light. It lived in the iron lantern that hung from the oak in front of the Green Man in Shrewford Admiral. He’d heard the Pennel clock strike twelve, and soon the lamp would go out because Mistress Dalton stumped out of her back room at midnight every night and made a great noise with her stick on the beams in the kitchen and drove the last drinkers out. Any minute now the crew of them would be grumbling in the lane outside the Green Man--Joe the tinker, and Peter, and Jonas, and Tom Devitt who had sailed with Drake, and the other Tom, Long Tom Bolling from Pennel.

But the rest of the world was asleep. The cattle were asleep in the fields, and the people were asleep in their beds--his father in his wide bed (but cold, because his mother was dead and his father had no wife now), his sister Molly in her narrow bed, Sir Tristram Pennel in his high bed, old Voy the poacher in--but no one knew where Voy slept from night to night. The horses were asleep in the stables, heads hanging and three legs stiff and one leg bent. Parson was asleep in the rectory, and all the dead people in the ground, and--Mary was waiting for him.

He started and began to move with quick, quiet steps towards the vale.

If he met anyone they might ask where he was going at this time of night. But now there was a dim footpath under his shoes, and it was no crime to tread a footpath. The Pennel gamekeepers might think he was poaching, but he wasn’t. It was good to creep along and be afraid, when you had, yourself, in your head, made the people you were afraid of, the ones who were hunting you. It wasn’t right to be afraid of real people though, if you could help it. He was twenty, and he could use bow, sword, sling, and halberd. He had fired guns and lain with girls. He could sing a madrigal and tune a fiddle; he could dance the Moorish dance at Whitsun and join in the Ring at the harvest fair. He could drink to King Charles in ale or brandy or wine--just as he wished. He could ride a horse and milk a cow and plough a straight furrow with two oxen at the plough. Sickle, billhook, and scythe wrought comfortably in his hands, and his fingers could hold the bull by the nose. He could not read or write.

He was a man. Boys played at make-believe; for a man, it was silly. Perhaps it was even sinful, but he couldn’t help it.

He said to himself, ‘It is an ordinary summer night,’ and tried hard to see only what his eyes showed him. But really, nothing was ordinary. Up there on the Plain, where the wind blew close to the earth and at night the larks started out of their shelters at your feet, there were long, quiet humps, and they were not ordinary. A ploughman had turned up statues and stone arrowheads there not long ago. Across the vale, above the Wansdyke, a farmer digging his well had found a man’s spine with a rusted sword broken off in it, and bones that turned to powder when he picked them up. By Shrewford Ring two stones stood ten feet high in the middle of nothing, and a third stone lay flat over them. The three stones made a bulky and dangerous shape up there, and in the broad sunlight of day--time he could not guess what they were for. At night, some--times, he could--but he dared not tell anyone what he guessed, because it was dark and full of animals and witches. As a boy, he had asked his father about the stones, but his father couldn’t answer him. As a youth, he’d asked Parson, and Parson had said, ‘Romans, Jason. Romans and heathens and Druids, Jason. Have you learned your catechism, Jason? Have you had any sinful thoughts?’ Parson was sly and fat and liked to make fun of the farmers because they could not read.--Jason groaned. There was so much to know, and he knew nothing except to be a farmer’s son in Shrewford Pennel, in the county of Wiltshire, in the year of Our Lord 1627.

The church clock struck a single note. Half-past twelve? Or one? He’d kept Mary waiting a long time already. He walked quickly down the path and soon came to a stream ten paces wide. It ran noisily now, at night, over its stones. A heavy plank bridge crossed it in two parts, one from the near bank to a big stone in the middle, and one from the stone to the far bank. As Jason crossed, a fish swirled suddenly upstream. The lash of its tail flicked a spray of water into the moonlight and sent circles of ripples under the bridge and out to the banks. Jason watched the ripples till the sparkling shallows broke and swallowed them. Slowly he dropped to his stomach and lay on the plank, peering into the water.

‘Oh, I see you,’ he muttered, ‘and I could catch you, too.’

He glanced round. Sir Tristram’s keepers might have been watching him come down from the edge of the Plain. They might be watching him now. Then he’d get a beating, or worse. The law didn’t allow any such thing, and most of the squires didn’t allow it either. But the Pennels were ginger-haired and had narrow heads, and Sir Tristram was jealous of every fish in his streams and every rabbit in his warrens. His men had caught Jason half a dozen times already. Then Sir Tristram would curse him and swear he’d die on the gallows, and his father would get into trouble again, for not keeping him in order, and Parson would make a joke about it in his sermon next Sunday, but not pleasantly.

But--he could catch that fish. He rolled back the sleeve of his shirt and stretched his arm down into the water. He half clenched his fist and slid his hand slowly along under the overhanging bank, moving his fingers and gently stirring the water, just as a trout’s tail would do.

Ah, and what does the fish see? It will be green and dull and swirly, all that he sees. People are nothing but shadows that pass across the light, and they don’t look like people, they are bent and short the way a stick is when some of it’s in the water and some isn’t. A man walking is a thump-thump on the earth, which makes a noise in the water, but not a noise you hear, a noise you feel, like when they fired the big cannon over at Amesbury and Jason felt it here. And the swirling and the blunt shape, greeny-bluey and gently stirring--that’s not Jason’s hand, that’s another trout--not a pike for the pike moves fast, turns quick . . .

His hand cupped under the belly of the trout, and he moved his fingers up and down, tickling, touching--a pound, a pound and a half. Flip him out, and then a fire of dry wood; wait till the wood turns to red coals. . . .

The clock struck two. It must have been half-past one he’d heard before. Mary was waiting. He didn’t know why she’d become his girl when she had been all but betrothed to George Denning, but so she had, and his father told him it was time he got married so that when his sister married the fool Ahab Stiles she had got herself betrothed to, and went away, there would still be a woman to cook the food and keep the chickens. He’d have to get married some time, and then it wouldn’t be right to stay out late at night. Clang, dang, the old clock would go, and about eight every night he ought to be home, and the trout would swim unseen in the Avon, and the broad leaf gleaming in the bush would never be a golden helmet, but only a leaf.

He walked down the lane, dry and hot and deep, that ran between the churchyard and the back of the Bowchers’ cottage. The moon shone full on Mary’s window now. He was a fool to be so late. Two hours ago he could have climbed in shadow. Now any inquisitive old fool in the village could see him if she chose to look. The casement was open, and that was the sign that nothing was wrong. Mary was a good girl. For a moment, standing with one hand on the ivy, he thought of her. She was kind, and when she smiled it was slow and didn’t hurt, and her hands were hard as his, but her thighs were soft and her lips wet. He was very fond of her.

He looked up at the wall. Now the best way was to use the ivy to the right of her casement. Old Bowcher slept with his wife on the ground floor at the other side of the cottage. Jason needn’t fear disturbing them unless he fell off, and even then--he could hear them snoring, and smiled.

He’d never tried climbing the ivy on the left. There was a gap of four feet, nearer five, between the ivy and the casement up there, but he could swing across that and catch hold of the sill. He’d been up on the right so often that it wasn’t exciting any more.

He began to climb on the left. He went up easily and quietly, hand over hand. It was fine, his muscles easy and strong and moving the way he told them. This was how Tom Devitt had climbed the side of the Spanish galleon in Cadiz harbour, he said--the moon was a lamp swinging at the masthead as the great ship rocked. The water lapped far below, the glowing water, warm and full of light. Winged golden fish scuttered across the surface, leaving sparks of water-fire behind. The crew paced the deck with bare feet. They challenged one another in their strange language--

’Raval push millowo?’ ‘Groton smahooken! Ta mien? Hellog she varam!’

A sharp steel sword swung naked at Jason’s belt, and the next man hung on the rope below him, and the little boat waited with muffled oars, and it was full of their dark, eager, bearded faces, and the English ship lay hidden in the mist beyond. . . .

It looked a long way to the casement. He reached out as far as he could--short by two feet. The ivy was not so strong on this side either. He could go down again easily enough, and climb up the other side.

One of the Pennels had captured Alton Castle for King Harry this way, swinging in from a tree to an arrow slit and strangling the sleepy soldier on guard there.

He leaned back, moved his feet until the ivy stopped creaking, and jumped. His hand grasped at the window-ledge, and his head hit the casement with a bang. As his fingers gripped, he heard a gasp from inside the room. He drew himself up, suddenly tired now that the excitement was over and it was only Mary Bowcher’s window, and only Mary leaning out to pull him in.

As soon as he was inside she whispered anxiously, ‘What happened, Jason? Are you hurt?’

She wouldn’t understand about Drake and Alton Castle, so he muttered, ‘The ivy nearly gave way.’ He didn’t like to lie, but people often forced him to, because they wouldn’t accept the truth. To them a lie was often truer than truth--like the time when he didn’t go to catechism and told Parson he’d been thinking about the three stones at Shrewford Ring, which was the truth, but Parson had called him a liar. Next time he said he’d been drinking beer in the Cross Keys, and Parson believed him.

Mary was strong and short, with big breasts and sunburned arms. Her hair was thick and straight and hung down in a brown cloak over her shoulders and breasts and back. Beyond her he saw the bed in the corner, under the slope of the roof. You had to stoop there, and one of the boards groaned when you trod on it. Mary was twenty-two, and she slept naked because her father was only a labourer on the Pennel estate. In the winter she slept in her shift. The blankets were coarse and dark, and the only other pieces of furniture in the room were a short bench, a square table, and a big chest of drawers. The heavy smell of night-scented stock came in through the window, mixed with the acid tang of bruised ivy and the sharp, cold smell of the gravestones; but Mary noticed only the good smells of the cows, which she knew, and of the flowers, which she knew.