Coronation Everest

Read Coronation Everest Online

Authors: Jan Morris

JAN MORRIS

For

HENRY MORRIS

born on page 115

and for those who have climbed on

This little book is a work of historical romanticism. It recalls the almost simultaneous occurrence of two events – a young queen’s coronation, the first ascent of a mountain – which profoundly stirred the British nation fifty years ago. The queen was Elizabeth II of England. The mountain was Mount Everest, the highest of them all, climbed at last by a British expedition after decades of failed attempts.

It is hard to imagine now the almost mystical delight with which the coincidence of the two happenings was greeted in Britain. Emerging at last from the austerity which had plagued them since the second world war, but at the same time facing the loss of their great Empire and the inevitable decline of their power in the world, the British had half-convinced themselves that the accession of the young Queen was a token of a fresh start – a new Elizabethan age, as the newspapers like to call it. Coronation Day, June 2, 1953, was to be a day of symbolical hope and rejoicing, in which all the British patriotic loyalties would find a supreme moment of expression: and marvel of marvels, on that very day there arrived the news from distant places – from the frontiers of the old Empire, in fact – that a British team of mountaineers, led by a British soldier, Colonel John Hunt, had reached the supreme remaining earthly objective of exploration and adventure, the top of the world.

Things were different then. On the one hand space travel was yet to come, and the ascent of Mount Everest, since climbed by hundreds of people of all nationalities, was enough to thrill everyone. On the other hand the British monarchy was at an apex of its popularity. The moment aroused a whole orchestra of rich emotions among the British – pride, patriotism, nostalgia for the lost past of war and derring do, hope for a rejuvenated future, satisfaction that Everest, essentially a British sphere of influence (as the old imperialists would have said) had been first climbed, as it should be, by the British. People of a certain age remember vividly to this day the moment when, as they waited on a drizzly June morning for the Coronation procession to pass by in London, they heard the magical news that the summit of the world was, so to speak, theirs. They cheered and sang as the news spread around the waiting crowds, and went on to ring the world.

Very improbably, for I am a lifelong republican, I was the newspaper correspondent who arranged this happy conjunction, and

Coronation Everest

explains how it happened. The book, which I wrote in the 1950s, needs to be read with a strong dose of historical sympathy, for everything has changed since then. I have changed myself – I was living and working as James Morris in those days – but the British nation has changed hardly less. Few moments now, certainly not a royal moment, can embrace the entire nation in such unity; and few exploits of adventure, I suspect, could be accepted with such uncomplicated pleasure. It was as though a family was celebrating, and its celebrations were infectious, too, and were shared by other peoples everywhere. Half a lifetime later, wherever I go someone is sure to raise the subject of my association with Everest and the Coronation,

and they nearly always speak of it in a tone of wistful affection, as a memory from simpler times.

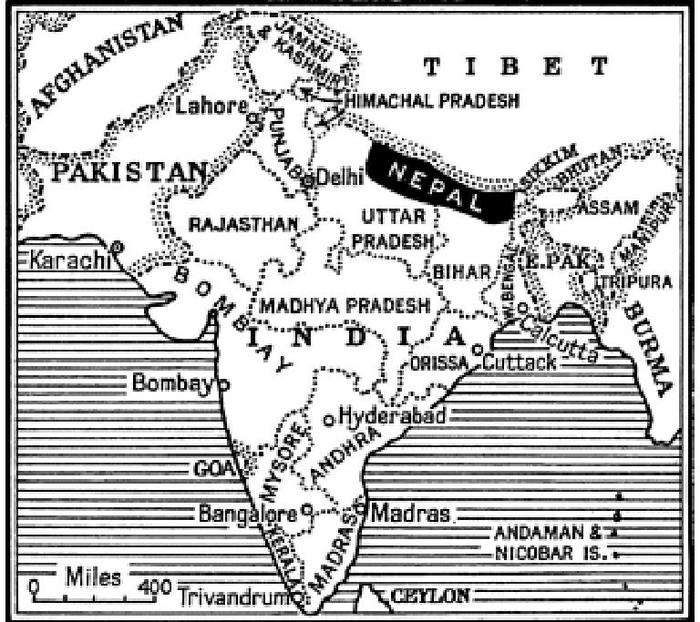

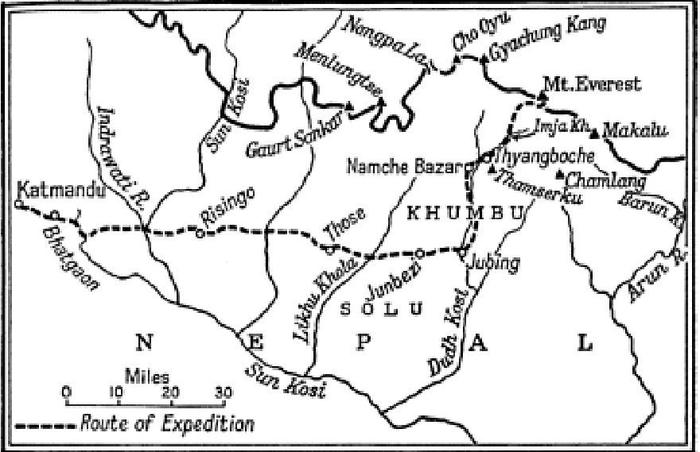

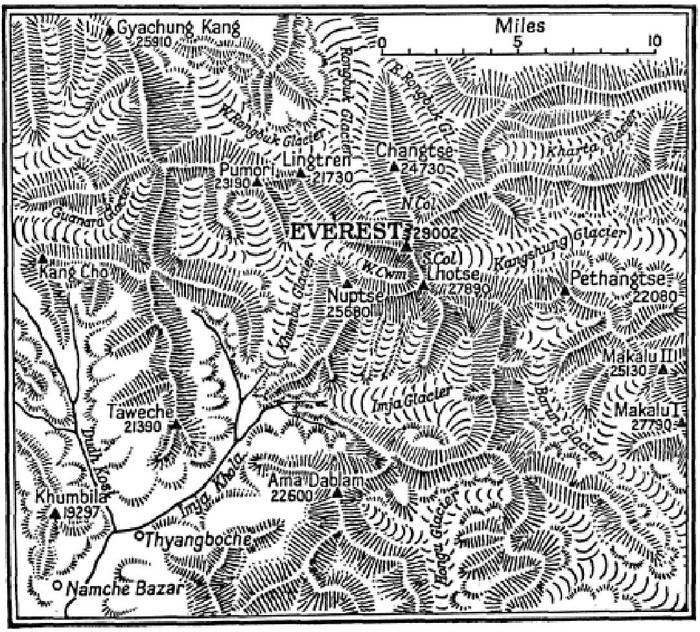

Of course it did not seem in the least simple in 1953, certainly not my own part in it, for getting the news back from Everest was a complicated technical task, and a fateful challenge for a young reporter like me. For more than thirty years there had been expeditions to Everest, which stood on the frontier between Nepal and Tibet. The first reconnaissance expedition, travelling through Tibet, reached the mountain in 1921, and was followed by five full-scale British attempts in the years between the world wars. After the second war British and Swiss expeditions both reached the mountain from the southern side, through Nepal. There were two wild but dauntless one-man expeditions, the first of which ended tragically, and in the early days of high-altitude flying there had been an aerial expedition over the summit.

Yet Everest had never really been ‘news’, in the big-time sense that it was in 1953. In the old days an assault on the highest of peaks had been essentially an adventure for gentlemen, tarnished by no cheap nationalist ambition, unspoilt by the stridencies of publicity. An Everest expedition was a group of English sportsmen, attended by their native servants, trying to climb an impossibly difficult hill in a ludicrously distant place, and quietly risking their lives in doing so. The world did not watch their efforts with any feverish interest. No element of passion pursued their attempts. The great public was not much interested.

A fragrance of English oddness is left to us from those early expeditions. The Abominable Snowman first made his appearance not as a figure of vulgar fun, or material for scientists, but rather as a strange squire of the snows, moving sedately if a little lumpishly through his remote

estate. Many of the climbers were notable for pungency of wit, splendid independence, or colourful bigness. Everest had not been cheapened or distorted, and those who climbed upon it formed an exclusive society of adventurers. It was proper that the one London newspaper which did concern itself with the venture from the beginning was

The Times

, then the proud but somewhat eccentric organ of the establishment.

In return for financial backing,

The Times

secured the copyright of dispatches from almost all the pre-war expeditions, and became the accepted channel of information from the mountain at a time when most other papers took little serious notice. The leader of each expedition undertook, as part of his duties, to ‘write the dispatches for

The Times

’. There was no hectic newsroom flavour to this kind of journalism. From time to time the mountaineer would collect his writing materials about him, closing the flap of his tent to keep out the wind, and settle down to describe the progress of the attempt much as he might write to complain about the pollution of a trout stream, or invite contributions to some charitable fund. Graceful and entertaining was the writing of most of these climbers, marred by no Fleet Street clichés, with no axes to grind and only the gentlest of trumpets to blow.

By 1953, when John Hunt’s expedition was completing its preparations in England, the news value of the mountain had been transformed. People no longer went to the Himalaya only for the fun of it, because sport was now a chief medium of nationalist fervour. The French had climbed Annapurna with a flourish of national pride. The Swiss had made two attempts on Everest, and nearly climbed it. People were beginning to call Everest ‘the British mountain’, just as they called Nanga Parbat ‘the

German mountain’. Besides, was it not Coronation year, the start of the new era, the rebirth of Britain, and all that? This time the news from Everest was going to be hot indeed.

The Times

, on whose editorial staff I then worked, again had the copyright to dispatches from the expedition; but it could clearly no longer afford to rely upon climbers’ journalism, produced when opportunity offered in the knowledge that only one newspaper was really concerned. This time there would be strong competition for the story, fanned by nationalist sentiment and honest patriotic pride, even fostered by the two current cold wars – between Capitalism and Communist, between East and West. It became obvious to everyone that this time the Everest party must (swallowing its natural revulsion) include in its number a professional journalist, concerned only with the problems of getting the news home to England. Nobody much liked the idea, if only because the expedition was big enough already; but Hunt, kindliest of commanders, digested the fact that I had never set foot on a big mountain before and even summoned up a wan smile as, over lunch one day at the Garrick Club, he invited me to join his team as Special Correspondent of

The Times

.

Coronation Everest

is the record of my assignment. I wrote the book soon after the event, in the pleasure of its aftermath, so please treat it with indulgence. Its excitements are those of long ago, and so are many of its attitudes.