Crazy Horse and Custer: The Parallel Lives of Two American Warriors (14 page)

Read Crazy Horse and Custer: The Parallel Lives of Two American Warriors Online

Authors: Stephen Ambrose

Tags: #Nightmare

In his sixteenth summer, 1858, Curly joined Hump, Lone Bear, Little Hawk, and other young warriors on a war party headed west. They went farther than any Oglalas had previously traveled, all the way to the Wind River, in central Wyoming, the land of the Shoshonis (or Snakes, as the Sioux called them) and the Arapahoes, just south of Crow country. A scout located an Arapaho village with many fine horses. The Sioux had never seen the Arapahoes, did not understand their language, but were confident that they were more than a match for these strange people, so they decided to attack immediately.

Curly prepared himself in the proper way, as he had been told in the dream and as he would do before every battle of his life. He already wore a small stone behind his ear; now he put a single hawk’s feather in his hair, painted a zigzag line with red earth from the top of his forehead downward and to one side of his nose on to the base of his chin. He then put a few spots to represent hail on his body, passed some dust over his horse, and finally sprinkled a little dust on his hair and body. He was ready.

33

The Arapahoes had discovered the Sioux presence and before the war party reached the village, Arapaho warriors started firing. The Arapaho held the high ground. Hump led an attack, but the Arapahoes held firm. The Sioux had a man wounded, managed to kill one enemy, but for two hours the fight was a standstill.

Suddenly, Curly gave a whoop and charged straight toward the Arapaho position. Arrows and bullets flew around him, but he rode on, right into the enemy. Curly counted one, two, three coup, then turned his horse and retreated, whooping and hollering, while the Sioux at the foot of the hill called out his name in honor of his bravery. Curly charged again and then again. His medicine, it seemed, was powerful; like the man in the dream, he rode through volley after volley of arrows and bullets without getting hit.

The last time Curly charged, two Arapahoes came forward to meet him. Curly killed one with an arrow, leaped his horse over the dead man, whirled, and shot the second man with another arrow. Then, with arrows from above and below him flying over his head, the air filled with the whoops of Arapaho and Sioux warriors, Curly jumped from his horse and took the scalps of the two dead men. Just as he lifted the second scalp, an arrow hit him in the leg. His horse jerked loose, and he had to flee downhill on foot.

Hump pulled the arrow from Curly’s leg, then dressed the wound

with a fresh piece of skin from a dead horse. Curly threw away the scalps—he had forgotten that he should never take anything for himself: because he had forgotten, the power of his dream had failed him and he was wounded. With one exception, he would never again take a scalp.

As soon as Curly’s wound was dressed the Oglalas decided that enough was enough and rode away, heading back to camp. When they arrived there was a victory dance. Twice, Curly was pushed forward into the circle and told to make a song in praise of his brave deeds, but each time he backed out, saying nothing.

The next day Curly’s father put on his ceremonial blanket and picked up his sacred pipe. Then he walked through the village, singing a song he had composed, a song that would give Curly a new name, a name he could hold to with pride for the rest of his life:

My son has been against the people of unknown tongue.

He has done a brave thing;

For this I give him a new name, the name of his father,

and of many fathers before him—

I give him a great name

I call him Crazy Horse.

After that the father was no longer called by the name he had given away, but by a nickname, Worm. And Crazy Horse joined Worm, and all the others, at a great feast in honor of his new name.

34

* Usually called simply Man Afraid. His son had the same name (which meant his enemies were afraid even of his horses). In this work, the father will be called Old Man Afraid, the son—about Curly’s age—Young Man Afraid.

† The probable explanation is that the shells were underloaded. Perhaps Ice was in collusion with the warrior, who may have cheated on the powder load.

CHAPTER FIVE

Autie

“My voice is for war!” George Armstrong Custer, aged seven

“What a pretty girl he would have made.”

Sara McFarland, on the sixteen-year-old Custer

George Armstrong Custer was born on December 5, 1839, in the tiny village of New Rumley, in Harrison County, Ohio. His father was Pennsylvania Dutch, descended from solid German citizens of the Rhineland who had immigrated to America in the eighteenth century in search of a better life. A sturdy people, these Custers had their full share of progeny, including Emmanuel Henry Custer, born in 1806 in Cresaptown, western Maryland. When he was eighteen years old Emmanuel followed the advancing frontier—and members of the large Custer clan who had already made the trek—to New Rumley, a town that had been laid out by his uncle Jacob in 1812.

1

Emmanuel, who wore a long flowing beard and had the stern countenance of the German burger, was a part-time farmer, part-time blacksmith. He married Matilda Viers, who gave him three children before dying untimely in 1835. Seven months later Emmanuel married Maria Ward Kirkpatrick, a widow from Burgettstown, Pennsylvania, who had three children of her own. Maria had an imposing chin, a narrow, hard-set mouth, slightly shrunken cheeks, and a thin but prominent nose that looked a little like a hawk’s beak. George, one of her sons by Emmanuel, inherited these physical characteristics.

Emmanuel and Maria had children of their own at closely spaced intervals; the first two died as infants, and George—nicknamed “Autie” by his family—was in effect the oldest child of the union. But in terms of his family experience, he was almost smack in the middle, with six older children from the previous marriages to look after him and four younger ones for him to lord it over. Remarriage on the frontier was common enough, and the Custers merged into a

solid family with evidently no difficulty at all. Although the family was by no means isolated, it was clannish—Autie spent his infancy almost entirely within the family nest. He was probably a pet of both Ma’s kids and Pa’s kids, who to him were simply brothers and sisters—as an adult, Custer could not recall who was whose child. As far as he was concerned, they were all Custers, no more, no less. That simple fact speaks eloquently for a healthy, warm, and happy family.

2

The Custers were fairly typical Americans, a part of the vast melting pot like so many other residents of Ohio. Maria was Scotch-Irish, Emmanuel was German, but the Custer family was American. The fact that the Custers were Methodists was one example of their rejection of the Old World ways; the Methodist Church played a leading role in bringing together Americans of different European backgrounds.

Autie’s experiences as an infant are unrecorded. He was probably nursed at Maria’s breast, although by 1840 bottle feeding was growing in popularity. Weaning, that first basic lesson in discipline, almost certainly came early, perhaps as early as eight months and clearly before he was much over a year old, for his brother Nevin was only eighteen months younger than he was. Toilet training was probably complete by that time, too; the child-raising literature of the period expressed disgust at wetness and lack of control and urged mothers to complete the job as quickly as possible. Training was accomplished through frequent changes of the child’s clothing, by placing the child on the “chair” for hours on end, and, in Autie’s case, through the example of older brothers and sisters. The training instilled in him the habits of cleanliness, regularity, obedience, and discipline, and probably something like a sense of shame at his own body’s functions. If he engaged in infantile masturbation he was probably warned off and punished if he persisted, for nineteenth-century Americans believed that masturbation would ruin a child, leading to disease, insanity, and even death.

3

As Autie grew older he was physically punished for transgressions, but although the Pennsylvania Dutch were noted for beating their children to force submission, Autie probably did not have it as bad as most boys his age, for Emmanuel Custer was a fun-loving sort who much preferred playing with his kids—or yelling at them—to whipping them. The atmosphere around the Custer home seems to have been joyous, especially in comparison to the mood at neighboring homes. Emmanuel was a practical joker and so were his children—Autie, worst of all. Chairs were always being pulled from

under someone just sitting down; the object of the joke laughed as loud as the others, for he or she knew that the shoe would probably be on the other foot next time around.

Maria was a strong woman who devoted herself to her children. They were at the center of her life, her only real care and concern. She fed and clothed them, hugged them when they needed it, listened carefully and sympathetically to their stories of their adventures, and generally fulfilled the idealized role of motherhood in American society. Not well educated herself, she did all she could to see to it that her children got the best possible educations. After the Civil War she wrote a revealing letter to Autie that began, “My loveing son,” and continued: “When you speak about your boyhood home in your dear letter I had to weep for joy that the recollection was sweet in your memory. Many a time I have thought there was things my children needed it caused me tears. Yet I consoled myself that I had done my best in making home comfortable.” Not for herself, Maria added, and she regretted that “I was not fortunate enough to have wealth to make home beautiful, always my desire. So I tried to fill the empty spaces with little acts of kindness. Even when there was a meal admired by my children it was my greatest pleasure to get it for them.”

A cynic might have seen her as not much more than a maid, or even a slave, ministering to every little want and desire of her children, denying herself always. Maria would not have agreed. She found her satisfaction, her reason for being, in raising happy, healthy children, a task she carried out with great success. As she wrote her son, “It is sweet to toil for those we love.” Autie returned her love in abundance. Throughout his life, even when he was a world-famous general, he hated partings from his mother; the partings were always emotional, with great hugs and flowing tears.

4

Emmanuel was a strong-willed, self-confident man who liked to roar out his opinions to make certain that everyone knew where he stood and understood him perfectly. He was also a free thinker: in a county of Whigs, he was the leading Democrat. He enjoyed debating the public issues of the day and did so at all opportunities. He took his politics seriously and regarded party loyalty as important as church denominational loyalty. “My first vote was cast for Andrew Jackson,” he wrote at the close of his life, “my last for Grover Cleveland. Good votes, both!”

Emmanuel was quietly but deeply religious. He helped found the Methodist Church in New Rumley and would go there to pray for guidance on the burning political questions of the times. He regarded

card playing, drinking liquor, dancing, and a host of other pleasures as sinful, did not indulge himself, and was rather successful in keeping his children away from forbidden fruit. During the Civil War he wrote his daughter-in-law, “I have every confidence in my dear son Autie, surrounded as he is by temptations … but, Libbie, I want you to counsel Thomas [Autie’s younger brother, also in the Army]. I want my boys to be, foremost, soldiers of the Lord.”

5

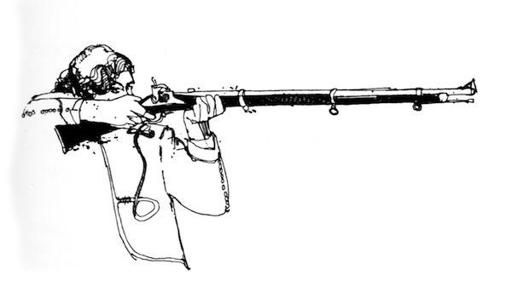

Emmanuel was no soldier himself, although as a respectable member of the community he did belong to the local militia, grandly called the New Rumley Invincibles. Emmanuel took Autie to drill meetings with him, dressing the boy in a tiny suit of velvet with brave big buttons. By the time he was four years old Autie could go through the manual of arms perfectly; the militiamen called him “a born soldier.”

6

Autie was impulsive and somewhat precocious. Emmanuel later described a childhood incident: “When Autie was about 4 years old he had to have a tooth drawn, and he was very much afraid of blood. When I took him to the Doctor to have the tooth pulled it was in the night & I told him if it bled well it would get well right away, and he must be a good soldier. When we got to the Doctor he took his seat, and the pulling began. The forceps slipped off, and Doc had to make a second trial. He pulled it out, and Autie never even scrunched. Going home, I led him by the arm. He jumped & skipped, and said, ‘Pop, you & me can whip all the Whigs in Ohio!’ I thought that was saying a good deal, but I didn’t contradict him!” In fact, Emmanuel quoted him to everyone he met for weeks afterward.