Crazy Horse and Custer: The Parallel Lives of Two American Warriors (24 page)

Read Crazy Horse and Custer: The Parallel Lives of Two American Warriors Online

Authors: Stephen Ambrose

Tags: #Nightmare

But Collins was not typical. President Lincoln needed every officer of ability he could get his hands on to direct his armies in the Civil War; the Army on the Plains got what was left. With the notable exception of Colonel Collins, that wasn’t much. Most of the generals and colonels on the frontier were nothing more nor less than buffoons. As George Hyde puts it, “the ignorance of some of these superior officers was really amazing.”

6

One general reported in August 1864 that “the Snakes, Winnibigoshish, and Minnesota Sioux” were raiding west of Fort Laramie. The Minnesota Sioux (Santees) were in fact on the Missouri River, hundreds of miles north and east of Fort Laramie, while Winnibigoshish is a lake.

7

These officers had their poorly disciplined and badly organized troops marching back and forth across the Plains in futile search-and-destroy missions, while the Indians went merrily about their way, attacking settlements and stagecoach stations. The Indians then disappeared onto the prairie, and the soldiers trudged their way to the scene of the outrage, getting there days after the attack. The Indians, meanwhile, would hit the area the soldiers had vacated.

Soldiers chasing the Santees shot at every Indian they saw, provoking such widespread hostility that all the whites along the frontier, from Fort Laramie clear down to Texas, feared for their lives. They demanded protection so loudly that the Lincoln government had to respond. The fresh troops shot more Indians and a general Indian uprising followed.

Throughout the summer of 1864 the southern Oglalas, Cheyennes, and other tribes raided or otherwise harassed the whites. It was a classic guerrilla campaign, albeit that the Indians acted haphazardly and without any hint of central direction. Most often, the Indians attacked in very small groups, a half dozen men or less. The Plains and its people were the ocean in which these fish swam, and the white soldiers could not keep up with them. The United States was discovering that for all its industrial might, it was exceedingly difficult to bring its power to bear on its frontier or, once having gotten the power there, to use it effectively. The Indians knew the terrain; the whites did not. Indians could live off the country; the whites could not. The Indians were mobile; the whites were not. The Indians had the initiative; the whites did not. So there was a terrible anger among the whites, and a humiliating frustration. When these elements were combined with inept leadership, the resulting brew was dangerous.

Crazy Horse was a part of the campaign. According to fur-trader Billy Garnett, Crazy Horse and a childhood friend, Little Big Man,

operated as a team that summer, living in one of the hostile villages for a few days, then striking out again. Together, Garnett said, they “carried on a lively business in horse stealing and the killing of white people.”

8

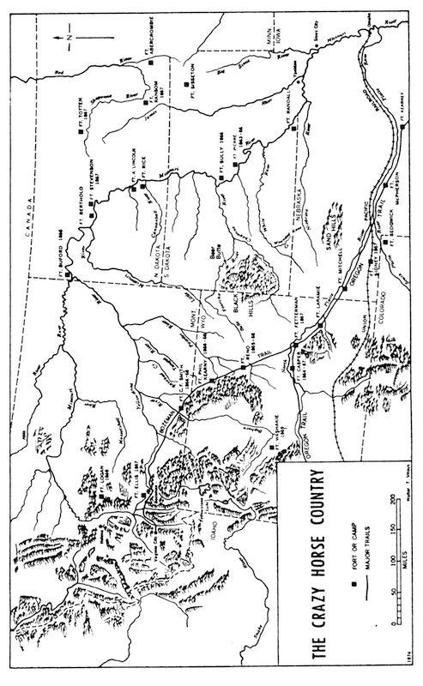

Along with hundreds of similar small teams they managed to stop the western flow of white emigration. Crazy Horse and the other Indians burned wagon trains and ranches, robbed and destroyed stagecoach stations and telegraph offices, laid waste to private dwellings for hundreds of miles on all the various lines of travel from the Missouri River to the Rocky Mountains, most especially the Holy Road. It was not a thought-out campaign, nor a concerted one—Old Man Afraid never brought the main body of northern Oglalas into it—but it was marvelously effective.

9

Under the circumstances, it was hardly surprising that panic seized the frontier. Governor John Evans of Colorado Territory issued a proclamation in August 1864, urging citizens to form themselves into parties to hunt down the Indians, killing every hostile they might meet. The proclamation was about as harmful as anything could have been. It put every ·friendly Indian in jeopardy, at the mercy of the whites; it created what amounted to free-fire zones; it invited revengeful emigrants who had been harassed by hostiles and any white man who coveted an Indian’s pony or wife to shoot to kill. Of course, the only Indians they could find were friendly, and for every one they shot, five friendlies or more turned hostile. Evans had armed bands of whites roaming the countryside, murdering innocent Indians, while the Indians had their armed war parties out murdering whites. In this struggle, the Cheyennes and their Sioux and Arapaho allies got much the best of it.

10

The military commander in Colorado was Colonel John M. Chivington, a boastful, arrogant, stupid man. He was urging every white man he met to kill all Indians seen, “little and big.”

11

In November 1864, in collusion with other Army officers, Chivington induced Black Kettle and his Cheyenne band to camp at Sand Creek, southeast of Denver between the Smoky Hill and Arkansas rivers. Black Kettle was a leading friendly who wished to avoid war with the whites at all costs. His young braves were certainly guilty of many outrages, but neither he nor his band could properly be blamed. With fighting going on all around him, Black Kettle wanted to find a safe place to camp for the winter. The Army officers promised him protection if he would move to Sand Creek, about forty miles from Fort Lyon, Colorado. Black Kettle did as he was told, running up an American flag on a pole in the center of the village.

Chivington had raised an infantry regiment of hundred-day volunteers

in Denver, the 3rd Colorado, composed of all the riffraff on the frontier. Fortune seekers of every type, drunks, cardsharps, gun fighters, and all the Indian haters of Denver signed up for a grand campaign. Their sole aim, and Chivington’s, was to kill as many Indians as possible, as quickly and safely as it could be done, and then get back to the warm comforts of the whorehouses and gambling dens of Denver. It never occurred to them that killing friendlies only made more hostiles or that the whites did not have enough power on the frontier to cope with the general Indian uprising that would surely result from a massacre.

At dawn on November 29, 1864, Chivington and his six hundred men attacked Black Kettle’s camp at Sand Creek, which held about two hundred warriors and five hundred women and children. Chivington struck hard, but the Indians recovered and put up a stiff fight for three or four hours, inflicting forty-seven casualties. Indian losses in dead alone were three times that high. (Chivington later boasted that he had killed five hundred Cheyennes but, as was typical of officers’ reports during the Plains fighting, that was a grossly exaggerated body count.) Two thirds or more of the dead Indians were women and children. The white soldiers scalped the dead and cut up and mutilated the bodies. A few days later, between the acts of a theatrical performance in Denver, they displayed the scalps, including the pubic hair of the Cheyenne women. Yellow Woman, the Cheyenne whom Crazy Horse had rescued nine years earlier after Harney’s attack on Little Thunder’s village, was among the dead.

12

The Cheyennes who escaped now sent around a war pipe (although Black Kettle himself still held out for peace). Around eight hundred lodges of Indians, including southern Oglalas, Brulés, Arapahoes, and some southern Cheyennes soon gathered at the headwaters of the Smoky Hill River. If Old Man Afraid and the northern Oglalas received the war pipe they paid no attention to it, but individual warriors did set out to join the big camp, Crazy Horse among them. Most of these Indians had never before been on a winter war party, but they were so furious that they could not wait for spring. On January 7, 1865, they hit the stagecoach station at Julesburg, Colorado, on the South Platte River, southeast of Fort Laramie. After running the small cavalry detachment at Camp Rankin into its stockade a mile away, the Indians plundered the station, the store, and the stage company’s warehouse. The women brought up pack ponies, loaded them with plunder, and late in the day started back toward camp, the ponies so heavily burdened that they could barely move.

13

Over the next few days the Indians continued to raid

up and down the South Platte River, causing pandemonium. They took control of an area that would, three years later, be the scene of Custer’s first Indian campaign.

Fighting the United States could have its rewards. Crazy Horse had never seen so much loot in his life—this was ten, twenty, one hundred times better than raiding the Crows. George Bent, the half-Cheyenne son of an old trader, who went over to the Indian side after Sand Creek, later told George Grinnell, “I never saw so much plunder in an Indian camp as there was in this one. Besides all the ranches and stage stations which had been plundered—and most of these places had stores at which the emigrants and travelers traded—two large wagon trains had been captured west of Julesburg. The camp was well supplied with fresh beef, and there was a large herd of cattle on hoof.” Bent said the Indians had sacks of flour, corn meal, rice, sugar, and coffee, crates of hams and bacon, boxes of dried fruit, and big tins of molasses. There were all kinds of clothing and other manufactured articles. The Indians kept Bent busy explaining to them what this or that was used for. Canned oysters were a particular favorite. When Bent told one group of Indians that catsup, candied fruits, and imported cheese were indeed excellent fare, they mixed it all together for a huge meal—and were violently sick.

14

Crazy Horse and Little Big Man, who went along on other small war parties, continued to go out at night to raid the settlers. So completely had the Indians taken control of the South Platte Valley that their big allied village kept huge fires burning all night, to guide the returning war parties. When the braves were not out on raids, they danced through the night. Captain Eugene F. Ware, who was stuck inside Camp Rankin, could look at the blaze of the campfires. “We could hear them shrieking and yelling, we could hear the tum-tum of a native drum, and we could hear a chorus shouting. Then we could see them circling around the fire, then separately stamping the ground and making gestures. … We knew that the bottled liquors destined for Denver were beginning to get in their work and a perfect orgy was ensuing. It kept up constantly. It seemed as if exhausted Indians fell back and let fresh ones take hold …”

15

On February 2, 1865, the big village packed up and started north, the chiefs having agreed to strike out for the Powder River country, where they could join forces with Old Man Afraid’s Oglalas. As the women began to pack, some one thousand warriors set off for another attack on Julesburg. Crazy Horse served as a decoy, riding out with a small group to the gates of Camp Rankin, hoping to draw out the cavalry and lead the soldiers into an ambush. But the whites would

not budge, so the main body of warriors emerged from their concealment and, after circling the fort a few times, shooting and yelling, rode over to Julesburg and began to plunder the store and warehouse again. After removing whatever goods were left, they burned the buildings one by one in another effort to get the troops so angry that they would come out and fight. But the soldiers, rather sensibly, stayed where they were.

16

Most whites in the Platte River region were now absolutely terrorized. The ranking Army officers outdid each other in trying to shift the blame for this unmitigated disaster, meanwhile doing all they could to stay out of the Indians’ path. One colonel, after riding along the South Platte for one hundred miles and finding the road completely wrecked, all stage stations and ranches burned, the horses and cattle driven off, the telegraph poles destroyed and the wire removed, was so aghast at what he saw that he marched his men immediately back to the safety of the nearest fort.

17

When the huge Indian camp crossed the North Platte, southeast of Fort Laramie, Colonel Collins tried to attack with a detachment of his 11th Ohio Cavalry, but he had only two hundred men and the Indians easily brushed him aside. When Collins brought up reinforcements the next day the Indians attacked him, hoping to pick up some American horses and more arms and ammunition. Collins corralled his wagons, put the horses inside the corral, and made it clear that the Indians would have to work to take any horses from his command. An all-day, long-range fight ensued, with no casualties; the following dawn the Indians started north again, headed through the Sand Hills of western Nebraska to the Black Hills of South Dakota, then on to the Powder River in northern Wyoming. North of the North Platte there were virtually no whites, much less soldiers or forts.

18

“The march of this village of seven hundred to one thousand lodges was an amazing feat,” George Hyde writes. “These Indians had moved four hundred miles during the worst weather of a severe winter through open, desolate plains taking with them their women and children, lodges, and household property, their vast herds of ponies, and the herds of captured cattle, horses, and mules. On the way they had killed more whites than the number of Cheyennes killed at Sand Creek and had completely destroyed one hundred miles of the Overland Stage Line.”

19