Crazy Horse and Custer: The Parallel Lives of Two American Warriors (63 page)

Read Crazy Horse and Custer: The Parallel Lives of Two American Warriors Online

Authors: Stephen Ambrose

Tags: #Nightmare

Crazy Horse felt no such need. It never occurred to him that he needed to, or could, improve himself. Had anyone suggested it to him, he would not have understood. Crazy Horse did not want to be better than he was. He just wanted to

be.

* Partly because of the depression, Grinnell went west, to eventually become

the

authority on the Cheyennes.

† It must have been a rainy summer for the late July grass to have been as luxuriant as Custer said it was. Ordinarily the Hills’ grass turns brown in midsummer.

CHAPTER TWENTY

Politics: Red and White

“If I were an Indian, I would greatly prefer to cast my lot among those of my people who adhered to the free open plains rather than submit to the confined limits of a reservation.”

George Armstrong Custer

In 1875 the United States Government began to put pressure on the Sioux to sell the Black Hills. This action caused a political split among the Sioux, who in any event had never been able to present a solid front to the whites. Three major factions among the Sioux emerged over the question of selling

Pa Sapa.

These factions cut across all other divisions; the hostile Brulés, Oglalas, Hunkpapas, Sans Arcs, and other subtribes were divided against themselves, as were the agency Indians. The largest faction consisted primarily of agency Indians who believed that the Hills were lost anyway and that the Sioux ought to get the best price they could for them. Red Cloud and Spotted Tail, by far the most important men among the Sioux, were the leaders of the faction that was willing to sell for a decent price, and they represented a majority of all the Sioux at the agencies. White Swan and Charger told Doane Robinson in 1892, “The Indians at all of the agencies counciled on the matter and we believed that the government would pay us a good big price for the Hills, so we waited.”

1

As the remark indicates, the agency Sioux were beginning to learn how to live in a white man’s world. The whites were not going to get

Pa Sapa

for a few beads and a little whiskey, as they had the Holy Road. These agency Indians hardly went hunting anymore—the buffalo had disappeared from the Dakotas and only on the Powder and Yellowstone rivers in Wyoming and Montana were there sufficient buffalo to support a hunting existence. Red Cloud’s and Spotted Tail’s people lived on the government dole. When they came into the agencies, they gave up their chief asset—their fighting strength—and they had nothing left to surrender in return for the

white man’s goods. Nothing, that is, except the Hills, which the whites obviously wanted badly and which, Red Cloud and Spotted Tail reasoned, the Sioux could not hold onto anyway.

Not all of the agency Indians agreed. A second faction among the Sioux, led by Young Man Afraid, had abandoned the warpath in order to protect their helpless ones and to save the Sioux nation from total destruction. Young Man Afraid had followed his father to Red Cloud Agency, where he used his impressive skills to work for some kind of accommodation with the whites that would allow the Sioux to live—to live in peace and to live as far as possible in the old ways. In Young Man Afraid’s view, selling

Pa Sapa

would be a disaster for the Sioux way of life. Unwilling to fight the whites any longer, he was equally unwilling to sell the Hills.

The third faction, led by Crazy Horse and Sitting Bull, was also unwilling to sell the Hills, but unlike Young Man Afraid, it was determined to fight to keep them. An overwhelming majority of hostiles shared this view, although there were some Sioux on the Powder River who agreed with Red Cloud. Many of the younger warriors in the agencies, however, lent their support to Crazy Horse. These hot-blooded young men scarcely knew there was a political issue involved—they merely wanted a chance to win some honors for themselves. Living on the agencies was dull. The agents would not let the young men go out on war parties against the Crows and there was precious little hunting left in their areas. They were spoiling for a fight, and in the end they provided Crazy Horse with much of his fighting strength. There was a constant flow of Indians between the agencies in Nebraska and South Dakota and the hostile country in Wyoming and Montana, a flow that was highly beneficial to the hostiles, for the agency Indians lived in close contact with the whites and therefore had numerous opportunities to pick up firearms which they could sell to the hostiles. Consequently, the hostiles were better armed than ever before, with possibly as many as one out of four warriors possessing a gun of some type.

Crazy Horse needed the agency warriors for more than just their guns, however; he needed their numerical strength too, because the hostile camps were constantly dwindling. When Red Cloud went onto the agency after the treaty of 1868, he took about five thousand Oglalas with him. By 1874 almost that many more had joined him at his agency on the White River.

2

They were mainly families who found the living too hard or too dangerous in the hostile territory. The whites were always tempting them to come in, as were the agency Indians. Visitors from the agencies would sit around the

campfires on the Powder River and tell wonderful stories about life on the agencies. Every five days the Indians came to the agency from their scattered camps, the visitors said, and then the whites would turn the cattle loose. The warriors chased the cattle and killed them like buffalo, the women following with their big knives to butcher the cattle. Then there was feasting. You too can enjoy this good life, the visitors said, and then come out here in the summer for a real buffalo hunt and a little raiding against the Crows. No more hard winters … the temptation was difficult to resist.

3

In the winter of 1868-69 there had been fifteen thousand Oglalas living on the Powder River; by the winter of 1874-75 there were only about three thousand left, the others having moved to the reservation.

4

Even Touch-the-Clouds, the leading Miniconjou warrior, had moved down to Red Cloud Agency to try out agency living.

5

Touch-the-Clouds didn’t stay long. Pretending that cattle were buffalo made a mockery of Sioux life, and, besides, the agency Indians were not living fat, no matter what they told the hostiles. The truth was that the agents were corrupt. They accepted diseased cattle, rotten flour, wormy corn, and so on from the white contractors, then took kickbacks when the United States Government paid the bill. There was nothing for the Indians to do at the agencies; the people were undernourished at best, starving at worst. Red Cloud and Spotted Tail argued incessantly with their agents, demanding more and better food, to no avail. Both sides were trying to cheat. The government wanted to make a census, for example, but Red Cloud forbade it. The agents were certain that the Sioux exaggerated their numbers in order to get more rations on issue day, and Red Cloud indeed thought he had fooled the whites. Red Cloud insisted that he had at least six thousand Indians with him, a figure his agent said was much too high. Finally, in 1875, using military force, the whites made a careful census—and it turned out there were 9,339 Sioux at Red Cloud Agency, plus 1,202 Cheyennes and 1,092 Arapahoes.

6

Such foolish bickering, in addition to the conditions on the agencies, soon led Touch-the-Clouds to flee. He moved back to the Powder River country and rejoined the hostiles, camping for a while with Crazy Horse.

Crazy Horse was now the leader of his own band. Whites had started to call him a “chief,” but that was not an exact description. He certainly was not a chief in the sense that Bull Bear, Old Smoke, or Old Man Afraid had been, nor was his band a hereditary one. Rather, it was composed of families that shared his sentiments, mostly Oglalas but with other Sioux bands represented. They lived

with Crazy Horse because they respected him and wished to follow his leadership. It was a purely voluntary association, as Crazy Horse did nothing to encourage them to follow in his tracks. Nevertheless, by the summer of 1875 the “Crazy Horse people,” as they were now called, numbered about one hundred lodges, with between two hundred and three hundred warriors.

7

The Crazy Horse people, like all the hostiles, embraced an idea. Their loyalty was not to family or band or tribe, but to freedom. Nothing demonstrated this mood better than the association between Crazy Horse and Black Twin, No Water’s brother. After the troubles over Black Buffalo Woman, No Water had joined the agency Indians. Black Twin stayed out and became a leading hostile and a close friend of Crazy Horse. They did not allow a blood feud to develop; instead, they worked together for a common good.

In the summer of 1875 the whites invited Red Cloud and Spotted Tail to come once more to Washington for a summit conference with the Great White Father. Red Cloud was anxious to go—he enjoyed such trips and all the attention he received in Washington in 1870—but he was an adept politician who knew that nothing he agreed to would be valid without the consent of the hostiles. So he asked to have Black Twin and Crazy Horse brought along to represent the wild Sioux of the north. Red Cloud wanted these two irreconcilables involved, and he perhaps wanted them to see the power of the whites, as he and Spotted Tail had seen it five years before, so that the hostiles would realize what they were up against. Red Cloud’s request to have Black Twin and Crazy Horse brought along also indicates that he regarded them as the most important hostiles, although it is also possible that he realized there was no chance of getting Sitting Bull anywhere near a white man under peaceful conditions. In any event, Red Cloud had misjudged Black Twin and Crazy Horse; they indignantly refused to come to the agency, much less go to Washington. Red Cloud also asked Young Man Afraid to go along, to represent the more militant agency Indians, but he too refused.

8

The trip to Washington was a fiasco. Red Cloud and Spotted Tail thought they were going to the summit in order to lay before the President their complaints about the dishonest agents, but to their shock the only thing the government wanted to discuss was selling the Black Hills. The Sioux leaders said they had no authority to consider such a proposition and must return home to discuss it with their people.

9

When the Indian delegation got back to the Plains, Spotted Tail

insisted on visiting the Black Hills along with his agent, so that he could make a judgment for himself as to the full value of the Hills. He wanted to see the miners and see how much gold they were getting. The agent himself was anxious for the Sioux to get the best possible price, as that would give him more goods and money to distribute, and thus fatten his profits. Together, after the inspection, Spotted Tail and his agent decided that the Hills were worth $7,000,000 cash, plus rations and goods for the Sioux for seven full generations.

10

In September 1875 the whites sent a commission from Washington to Red Cloud Agency to discuss the sale. At all the agencies, and even among the hostiles, there were spirited arguments about what to do. The older Indians wanted peace and security and were willing to give up

Pa Sapa

to get it, but they disagreed among themselves over the price to demand. The younger agency men still would not hear of the sale at all, nor would the hostiles. It was a quarrel that involved every Sioux from the Missouri to the Yellowstone to the White to the Powder.

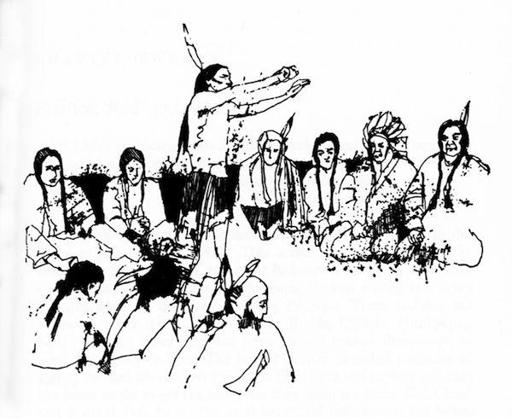

The council was held about eight miles east of Red Cloud Agency—Red Cloud and Spotted Tail were jealous of each other and engaged in a struggle for leadership, so neither would go to the other’s agency. The Brulés, Oglalas, Miniconjous, Hunkpapas, Blackfeet, Two Kettles, Sans Arcs, Yanktons, Santees, northern Cheyennes and Arapahoes were all represented, but not the Crazy Horse people. The agent had sent Young Man Afraid up to Crazy Horse’s country to ask him to participate. Young Man Afraid found nearly two thousand lodges in the Powder River country—it was the tag end of summer and there were many agency Indians still there—but no agreement about what to do. Game was scarce, even on the Powder River, and the whites promised a great feast; the temptation to come fill their bellies was alluring. Many hostiles went, but Crazy Horse and Black Twin held back. They said they might come in after a while, which Young Man Afraid knew meant never. Sitting Bull told Young Man Afraid that so long as there was any game left, he would never come in.

11

Crazy Horse was not a man to hold a grudge, as his close association with Black Twin showed, nor did he allow politics to stand in the way of friendship. Young Man Afraid urged him to come to the council, citing all the reasons why Crazy Horse should be present to represent the hostiles, but Crazy Horse was unmoved. He did not approve of what Young Man Afraid was doing (Young Man Afraid had recently become the head of the Indian police at Red Cloud

Agency) and insisted that any contact with whites spelled disaster for the Sioux. But they parted in friendship, with the crossed handshake of respect. Each man would follow his own trail, respecting the right of the other to do as he saw fit.

12