Crime at Christmas (37 page)

Read Crime at Christmas Online

Authors: Jack Adrian (ed)

The stories in this collection originally

appeared as follows:

Margery Allingham

'Murder Under the Mistletoe':

Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine

(US), January

1963.

Robert Arthur

'A Present for Christmas':

Detective Fiction Weekly

(US), 21 January

1939.

Nicholas Blake

'A Problem in White': as 'The Snow Line',

Strand Magazine,

February 1949. As

'A Study in White',

Queen's Awards,

4th Series (1949).

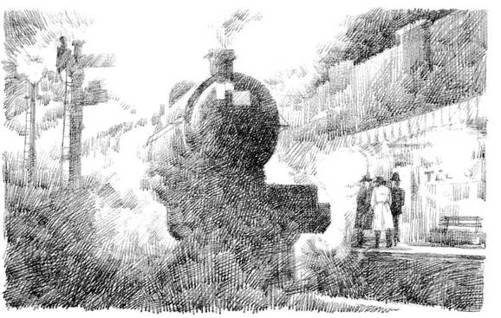

Anthony Burgess

'The Great Christmas Train Mystery':

Suspense

, December 1960.

John Dickson Carr

'Detective's Day Off':

Weekend,

25/29 December

1957.

Joseph Commings

'Serenade to a Killer':

Mystery Digest

(US), July 1957.

Cyril Hare

'Sister Bessie':

Evening Standard,

23 December 1949.

The Best Short Stories of Cyril Hare

(1959).

Edward D. Hoch

'The Three Travellers':

Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine

(US), January 1976

(as by 'R.L. Stevens').

Peter Lovesey

'Murder in Store':

Woman's Own,

21/28 December

1985.

James Powell

'The Plot Against Santa Claus':

Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine

(US), January

1971.

Will Scott

'Christmas Train':

Passing Show,

23 December 1933.

'Herlock Sholmes'

'The Secret in the Pudding Bag':

Penny Popular,

27 December 1924.

Julian Symons

'The Santa Claus Club':

Suspense,

December 1960.

Francis Quarles Investigates

(1965).

'Peter Todd'

'Herlock Sholmes's Christmas Case':

Magnet,

3 December 1916.

Edgar Wallace

'Stuffing':

John Bull Xmas Annual,

December 1926.

Ethel Lina White

'Waxworks':

Pearson's Magazine,

December 1930.

James Melville's

Santa-San Solves It

and Bill

Pronzini's

No Room at

the Inn

were written especially for this collection, and now appear in print for

the first time.

A PROBLEM IN

WHITE

The

solution to Nicholas Blake's puzzle-story is printed overleaf.

DON'T turn

the page until you've

read the first story

or

unless, having read it you can't stand the suspense any longer. . .

T

HE

Inspector arrested the Guard for the wilful murder of Arthur J. Kilmington.

Kilmington's

pocket had been picked by Inez Blake, when she pretended to faint at 8:25, and

his gold watch was at once passed by her to her accomplice, Macdonald.

Now

Kilmington was constantly consulting his watch. It is inconceivable, if he was

not killed till after 9 p.m., that he should not have missed the watch and made

a scene. This point was clinched by the first-class passenger, who deposed that

a man, answering to the description of Kilmington, had asked him the time at

8:50: if it had really been Kilmington, he would certainly, before inquiring

the time of anyone else, have first tried to consult his own watch, found it

was gone, and reported the theft. The fact that Kilmington neither reported the

loss to the Guard, nor returned to his original compartment to look for the

watch, proves he must have been murdered before he became aware of the loss,

i.e. shortly after he left the compartment at 8:27. But the Guard claimed to

have spoken to Kilmington at 9 p.m. Therefore the Guard was lying. And why

should he lie, except to create an alibi for himself? This is Clue A.

The Guard

claimed to have talked with Kilmington at 9 p.m. Now, at 8:55 the blizzard had

diminished to a light snowfall, which soon afterwards ceased. When Stansfield

discovered the body, it was buried under snow. Therefore Kilmington must have

been murdered while the blizzard was still raging, i.e. some time before 9

p.m. Therefore the Guard was lying when he said Kilmington was alive at 9 p.m.

This is Clue B.

Henry

Stansfield, who was investigating on behalf of the Cosmopolitan Insurance

Company the loss of the Countess of Axminster's emeralds, reconstructed the

crime as follows:

Motive.

The Guard's wife had been gravely

ill before Christmas: then, just about the time of the train robbery, he had

got her the best surgeon in Glasgow and put her in a nursing home (evidence of

engine-driver: Clue C): a Guard's pay does not usually run to such expensive

treatment; it seemed likely, therefore, that the man, driven desperate by his

wife's need, had agreed to take part in the robbery in return for a substantial

bribe. What part did he play? During the investigation, the Guard had stated

that he had left his van for five minutes, while the train was climbing the

last section of Shap Bank, and on his return found the mail-bags missing. But

Kilmington, who was travelling on this train, had found the Guard's van locked

at this point, and now (evidence of Mrs Grant: Clue D) declared his intention

of reporting the Guard. The latter knew that Kilmington's report would

contradict his own evidence and thus convict him of complicity in the crime,

since he had locked the van for a few minutes to throw out the mail-bags

himself, and pretended to Kilmington that he had been asleep (evidence of K.)

when the latter knocked at the door. So Kilmington had to be silenced.

Stansfield

already had Percy Dukes under suspicion as the organiser of the robbery. During

the journey, Dukes gave himself away three times. First, although it had not

been mentioned in the papers, he betrayed knowledge of the point on the line

where the bags had been thrown out. Second, though the loss of the emeralds had

been also kept out of the Press, Dukes knew it was an emerald

necklace

which had been stolen; Stansfield

had laid a trap for him by calling it a bracelet, but later in conversation

Dukes referred to the 'necklace'. Third, his great discomposure at the (false)

statement by Stansfield that the emeralds were worth £25,000 was the reaction

of a criminal who believes he has been badly gypped by the fence to whom he has

sold them.

Dukes was

now planning a second train robbery, and meant to compel the Guard to act as

accomplice again. Inez Blake's evidence (Clue E) of hearing him say

"You're going to help us again, chum," etc., clearly pointed to the

Guard's complicity in the previous robbery; it was almost certainly the Guard

to whom she had heard Dukes say this, for only a railway servant would have

known about the existence of a platelayers' hut up the line, and made an

appointment to meet Dukes there; moreover, to anyone

but

a railway servant Dukes could have

talked about his plans for the next robbery on the train itself, without either

of them incurring suspicion should they be seen talking together.

Method.

At 8:27 Kilmington goes into the

Guard's van. He threatens to report the Guard, though he is quite unaware of

the dire consequences this would entail for the latter. The Guard, probably on

the pretext of showing him the route to the village, gets Kilmington out of the

train, walks him away from the lighted area, stuns him (the bruise was a light

one and did not reveal itself to Stansfield's brief examination of the body),

carries him to the spot where Stansfield found the body, packs mouth and

nostrils tight with snow. Then, instead of leaving well alone, the Guard

decides to create an alibi for himself. He takes his victim's hat, returns to

the train, puts on his own dark, off-duty overcoat, finds a solitary passenger

asleep, masquerades as Kilmington inquiring the time, and strengthens the

impression by saying he'd walk to the village if the relief engine did not turn

up in five minutes, then returns to the body and throws down the hat beside it

(Stansfield found the hat only lightly covered with snow, as compared with the

body: Clue F). Moreover, the passenger noticed that the inquirer was wearing

blue trousers (Clue G); the Guard's regulation suit was blue; Duke's suit was

grey, Macdonald's a loud check—therefore the masquerader could not have been

either of them.

The time is

now 8:55. The Guard decides

to reinforce his alibi by going to

intercept the returning fireman. He takes a short cut from the body to the

platelayers' hut. The track he now makes, compared with the beaten trail

towards the village, is much more lightly filled in with snow when Stansfield

finds it (Clue H); therefore it must have been made some little time after the

murder, and could not incriminate Percy Dukes. The Guard meets the fireman just

after 8:55.

They walk back to the train. The Guard is taken aside by Dukes, who has

gone out for his 'airing,' and the conversation overheard by Inez Blake takes

place. The Guard tells Dukes he will meet him presently in the platelayers'

hut; this is vaguely aimed to incriminate Dukes, should the murder by any

chance be discovered, for Dukes would find it difficult to explain why he

should have sat alone in a cold hut for half an hour just around the time when

Kilmington was presumably murdered only 150 yards away.

The Guard now goes along to the engine and stays there chatting with the

crew for some forty minutes. His alibi is thus established for the period from

8:55 to 9:40 p.m. His plan might well have succeeded but for three unlucky

factors he could not possibly have taken into account—Stansfield's presence on

the train, the blizzard stopping soon after 9 p.m., and the theft of Arthur J.

Kilmington's watch.