CSS: The Definitive Guide, 3rd Edition (26 page)

Read CSS: The Definitive Guide, 3rd Edition Online

Authors: Eric A. Meyer

Tags: #COMPUTERS / Web / Page Design

Like horizontal

formatting, vertical formatting of block-level elements has its own set of

interesting behaviors. The default height of

an

element is determined by its content. Height is also affected by the width of the

content; the skinnier a paragraph becomes, the taller it must be to contain all of

the inline content within it.

In CSS, it is possible to set an explicit height on any block-level element. If

you do this, the resulting behavior depends on several other factors. Assume that the

specified height is greater than that needed to display the content:

In this case, the extra height has a visual effect somewhat like extra padding.

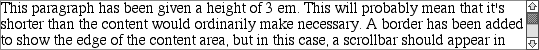

But suppose theheightis

less

than what is needed to display the content:

When that happens, the browser is supposed to provide a means of viewing all

content without increasing the height of the element box. The browser may add a

scrollbar to the element, as shown in

Figure

7-13

.

Figure 7-13. Heights that don't match the element's content height

In a case where the content of an element is taller than the height of its box,

the actual behavior of a user agent will depend on the value of (and its support for)

the propertyoverflow. This scenario is covered in

Chapter 10

.

Under CSS1, user agents can ignore any value ofheightother thanautoif an element is

not a replaced element (such as an image). In CSS2 and CSS2.1, the value ofheightcannot be ignored, except in one specific

circumstance involving percentage values. We'll talk about that in a moment.

Just as withwidth,heightdefines the content area's height, not the height of the visible

element box. Any padding, borders, or margins on the top or bottom of the element box

are

added

to the value forheight.

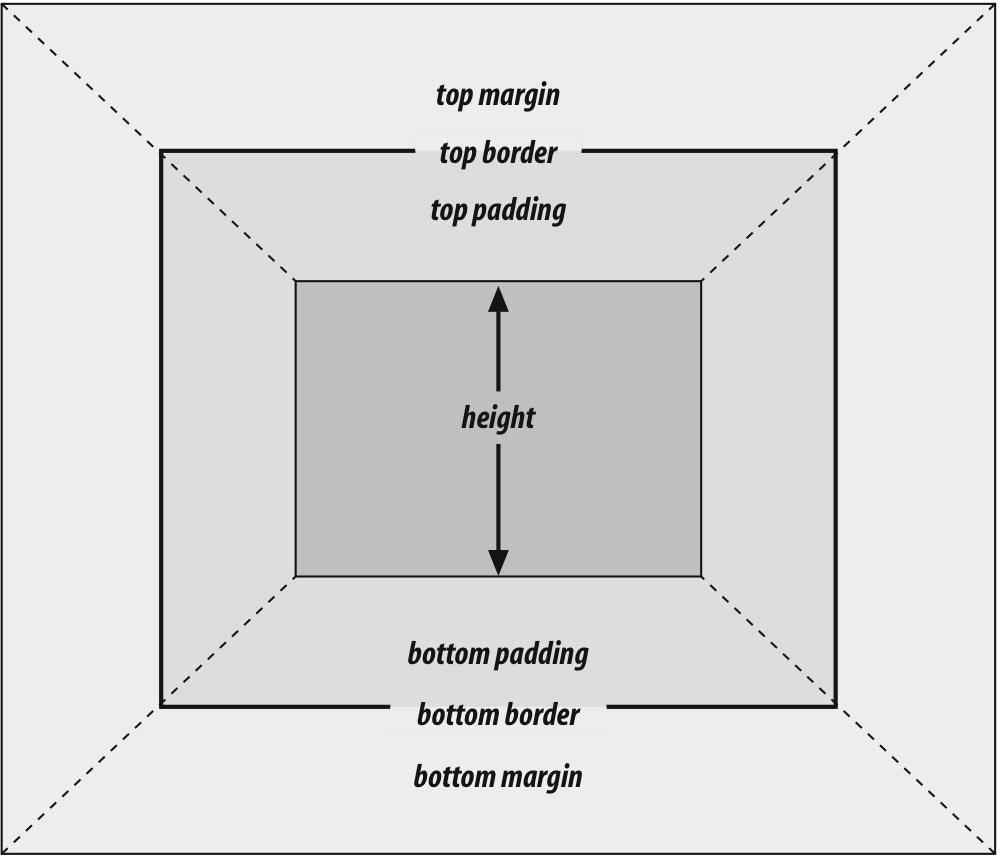

properties

As was the case with

horizontal formatting, vertical formatting also has seven related properties:margin-top,border-top,padding-top,height,padding-bottom,border-bottom, andmargin-bottom. These properties are

diagrammed in

Figure

7-14

.

Figure 7-14. The "seven properties" of vertical formatting

The values of these seven properties must equal the height of the

element's containing block. This is usually the value ofheightfor a block-level element's parent (since block-level

elements nearly always have block-level elements for parents).

Only

three of these seven properties may be set toauto: theheightof the element's

content and the top and bottom margins. The top and bottom padding and borders

must be set to specific values or else they default to a width of zero (assuming

noborder-styleis declared). Ifborder-stylehas been set, then the width of the

borders is set to be the vaguely defined valuemedium.

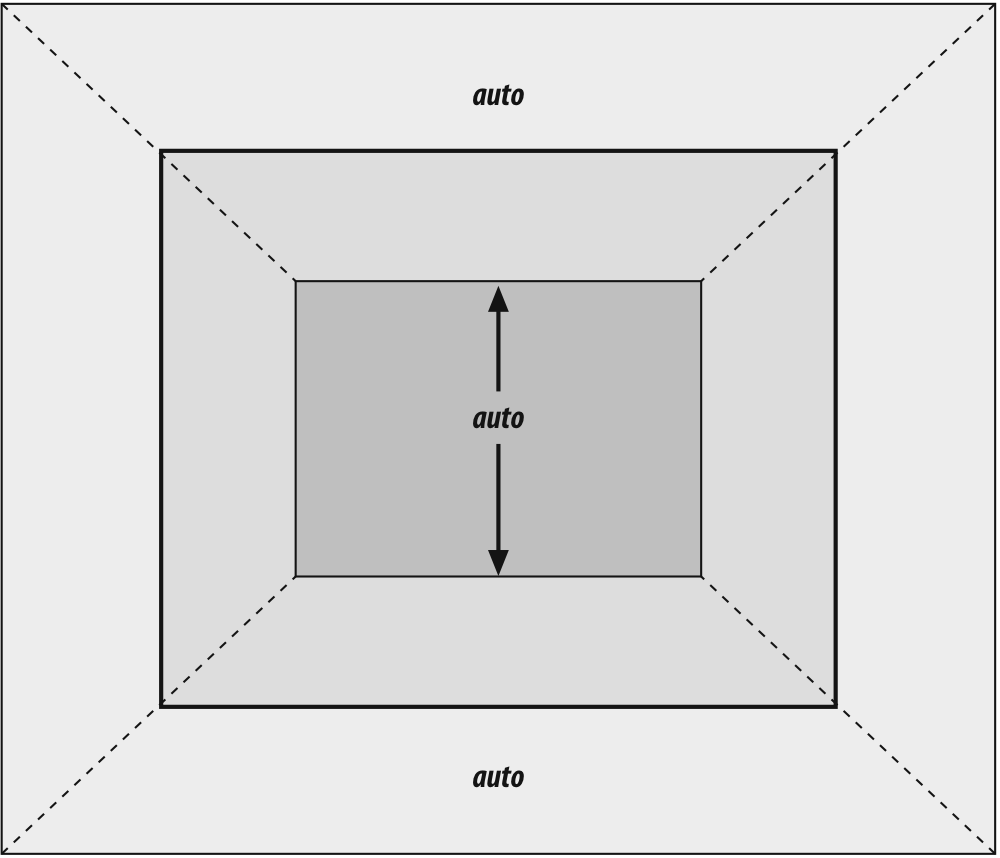

Figure 7-15

provides an illustration for remembering which parts of the box may have a value

ofautoand which may not.

Figure 7-15. Vertical properties that can be set to auto

Interestingly, if eithermargin-topormargin-bottomis set toautofor a block element in the normal flow, it

automatically evaluates to0. A value of0unfortunately prevents easy vertical

centering of normal-flow elements in their containing blocks. It also means that

if you set the top and bottom margins of an element toauto, they are effectively reset to0and removed from the element box.

The handling ofautotop and bottom

margins is different for positioned elements. See

Chapter 10

for more details.

heightmust be set toautoor to a nonnegative value of some type.

heights

You already saw how length-value heights are

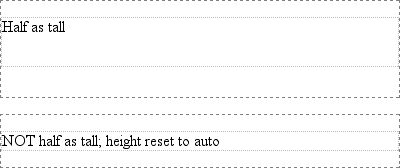

handled, so let's spend a moment on percentages. If theheightof a block-level, normal-flow element is set to a percentage,

then that value is taken as a percentage of the height of the containing block.

Given the following markup, the resulting paragraph will be 3em

tall:

Half as tall

Since

setting the top and bottom margins toautowill

give them zero height, the only way to vertically center the element is to set

them both to25%.

However, in cases

where theheightof the containing block is not

explicitly declared, percentage heights are reset toauto. If you changed the previous example so that theheightof thedivisauto, the paragraph will now be exactly as

tall as thedivitself:

NOT half as tall; height reset to auto

These

two possibilities are illustrated in

Figure

7-16

. (The spaces between the paragraph borders and thedivborders are the top and bottom margins on the

paragraphs.)

Figure 7-16. Percentage heights in different circumstances

In the simplest case, a block-level, normal-flow element withheight:autois

rendered just high enough to enclose the line boxes of its inline content

(including text).autoheight sets a border on

a paragraph and assumes no padding—expect the bottom border to go just under the

bottom line of text and the top border to go just above the top line of text.

If anauto-height, block-level, normal-flow

element has only block-level children, then its default height will be the

distance from the top of the topmost block-level child's outer border edge to the

bottom of the bottommost block-level child's outer border edge. Therefore, the

margins of the child elements will "stick out" of the element that contains them.

(This behavior is explained in the next section.) However, if the block-level

element has either top or bottom padding, or top or bottom borders, then its

height will be the distance from the top of the outer top margin edge of its

topmost child to the outer bottom margin edge of its bottommost child:

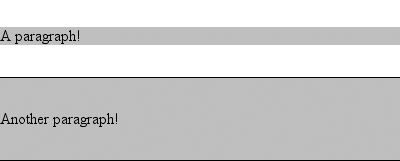

A paragraph!

Another paragraph!

Both of these behaviors are demonstrated in

Figure 7-17

.

Figure 7-17. Auto heights with block-level children

If you changed the borders to padding in the previous example, the effect on

the height of thedivwould be the same: it

would still enclose the paragraph's margins within it.

One other important aspect of vertical formatting

is the

collapsing

of

vertically adjacent margins. Collapsing behavior applies only to margins. Padding

and borders, where they exist, are never collapsed by anything.

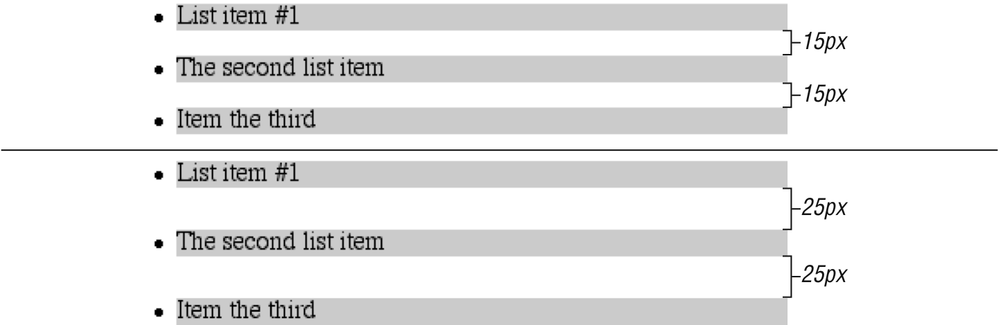

An unordered list, where list items follow one another, is a perfect example of

margin collapsing. Assume that the following is declared for a list that contains

five items:

li {margin-top: 10px; margin-bottom: 15px;}

Each list item has a 10-pixel top margin and a 15-pixel bottom margin. When the

list is rendered, however, the distance between adjacent list items is 15 pixels,

not 25. This happens because adjacent margins are collapsed along the vertical

axis. In other words, the smaller of the two margins is eliminated in favor of the

larger.

Figure 7-18

shows the

difference between collapsed and uncollapsed margins.

Figure 7-18. Collapsed versus uncollapsed margins

Correctly implemented user agents collapse vertically adjacent margins, as

shown in the first list in

Figure

7-18

, where there are 15-pixel spaces between each list item. The second

list shows what would happen if the user agent didn't collapse margins, resulting

in 25-pixel spaces between list items.

If you don't like the word "collapse," use "overlap." Although the margins do

not really overlap, you can visualize what's happening using the following

analogy. Imagine that each element, (for example, a paragraph), is a small piece

of paper with the content of the element written on it. Around each piece of paper

is some clear plastic, which represents the margins. The first piece of paper (say

anh1piece) is laid down on a canvas. A second

piece of paper (a paragraph) is laid down below it and then slid up until the edge

of its plastic touches the other paper's edge. If the first piece of paper has

half an inch of plastic along its bottom edge, and the second has a third of an

inch along its top, then when they slide together, the first piece's plastic edge

will touch the top edge of the second piece of paper. The two are now positioned

on the canvas, and the plastic attached to the pieces overlaps.

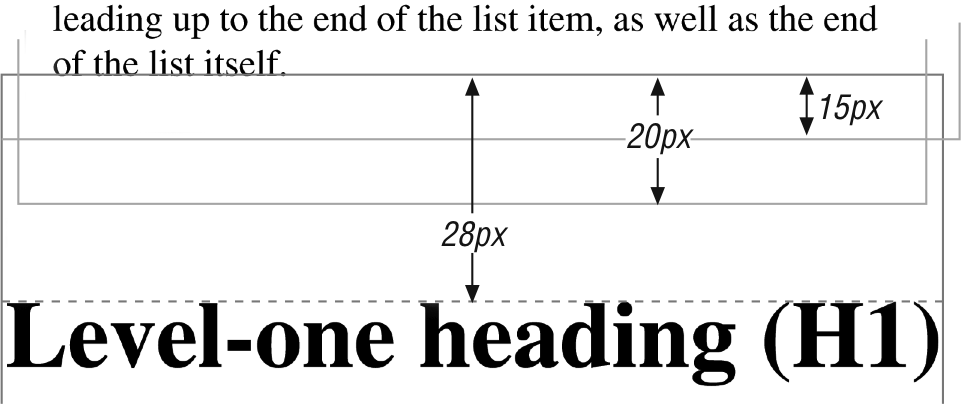

Collapsing also occurs where multiple margins meet, such as at the end of a

list. Adding to the earlier example, let's assume the following rules apply:

ul {margin-bottom: 15px;}

li {margin-top: 10px; margin-bottom: 20px;}

h1 {margin-top: 28px;}

The last item in the list has a bottom margin of 20 pixels, the bottom margin

of theulis 15 pixels, and the top margin of a

succeedingh1is 28 pixels. So once the margins

have been collapsed, the distance between the end of theliand the beginning of theh1is

28 pixels, as shown in

Figure 7-19

.

Figure 7-19. Collapsing in detail

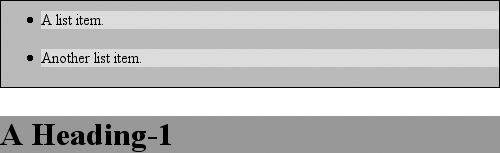

Now, recall the examples from the previous section, where the introduction of a

border or padding on a containing block caused the margins of its child elements

to be contained within it. You can see this behavior by adding a border to theulelement in the previous example:

ul {margin-bottom: 15px; border: 1px solid;}

li {margin-top: 10px; margin-bottom: 20px;}

h1 {margin-top: 28px;}

With this change, the bottom margin of thelielement is now placed inside its parent element (theul). Therefore, the only margin collapsing that takes

place is between theuland theh1, as illustrated in

Figure 7-20

.

Figure 7-20. Collapsing (or not) with borders added to the mix