Curse of the Gypsy (37 page)

Read Curse of the Gypsy Online

Authors: Donna Lea Simpson

Tags: #Mystery; Thriller & Suspense, #Cozy, #Historical, #Supernatural, #Werewolves & Shifters, #Women Sleuths, #Mystery, #Romantic Suspense, #werewolf, #paranormal romance, #cozy series, #Lady Anne, #Britain, #gothic romance

“Oh, yes,” he said. “Your room or mine, my lady, we will be together always.”

He sought her lips in the velvet darkness and she opened to him, the flame of desire burning bright. They made love again more slowly, knowing this was the first of many more times.

Author Afterword

Dear Reader,

As in the first two Lady Anne books, there are many historical facts behind the action in this work of fiction. I’d like to offer some pertinent information to those interested.

The hop plant is a flowering “bine”—unlike a vine, a bine does not have tendrils, but relies on stiff hairs to aid in climbing—and the cone-shaped flowers, or “hops” are used in the brewing of beer, adding the bitterness beer drinkers relish. Kent, England, became a center of hops growing in the sixteenth century, and at one time “oast” houses, the kilns or “kells” used for drying the hops flowers, were a ubiquitous part of the scenery. They were originally built as square towers with long, low additions, but in the nineteenth century they began to build them as round towers. However, it was later discovered that the original design was best, and they returned to the square tower. Many have lately been converted to dwellings.

Gypsy workers have always been a necessary part of the Kent agricultural season, appearing in spring to help with planting, staying through the hops harvest and the last crops of potatoes, and then moving on to find winter camps. To further explore the history of hops farming in Kent and the “gypsy travelers,” visit online sites, especially the BBC’s Web site, which offers many fascinating articles on the subject, or visit your local library.

There is some discussion in this work about the Somerset case, as well, a true case from 1772 that tested the legality of slave owning in England. James Somerset (or Somersett—both spellings are used, depending upon the source) was a slave who claimed freedom by virtue of his residence in England. Lord Mansfield, the Chief Justice of England, ruled that he was indeed free. It is a fascinating story, and I urge readers to learn more about James Somerset and Lord Mansfield, who gave his opinion that slavery was “so odious, that nothing can be suffered to support it, but positive law.”

His legal opinion was a rallying force for the abolition of slavery, and has been debated for more than two centuries. Almost more interesting is that Lord Mansfield’s great niece, Dido Elizabeth Belle, was the daughter of Mansfield’s nephew and a woman who was said to have been a slave, though that is uncertain. A lovely painting of Dido Elizabeth Belle and her white cousin, Elizabeth Murray, hangs at Scone Palace in Scotland.

I hope you have enjoyed this Lady Anne mystery,

Curse of the Gypsy

!

Fond regards,

Donna Lea Simpson

Also available from

Donna Lea Simpson

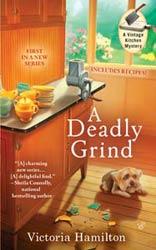

Donna Lea Simpson is also writing

cozy mysteries as Victoria Hamilton.

Take a quick peek at the first book

in her new series,

A Deadly Grind

,

available now from Berkley.

No one would expect to find a new love at an estate auction, but Jaymie Leighton just had; her heart skipped a beat when she first saw the Indiana housewife’s dream. She wasn’t in Indiana and she wasn’t a housewife, but those were just details. Tall, stately and handsome, if a little the worse for wear, the Hoosier stood alone on the long porch of the deserted yellow-brick farmhouse. The hubbub of the crowd melted away as Jaymie mounted the steps, strode down the creaky wooden porch floor and approached, reverently.

“You are so beautiful!” she crooned, stroking the dusty porcelain work top and gently fiddling with the chromed latch of the Hoosier cabinet cupboard, handled by so many generations of housewives before her eager, yet inexperienced, hands touched it. It was a

genuine

Hoosier, if the metal plate affixed above the top cupboards of the cabinet was to be believed, and she had no cause to doubt it. The latch of the long cupboard popped and the door swung open to reveal an intact flour sifter, mounted on a tilt-out pin.

“Wow,” Rebecca, Jaymie’s older sister, said, as she approached from the lawn below the porch railing.

“I

know

,” Jaymie said, standing back and tilting her head to one side, gazing at the piece with admiring eyes. “The latches work, at least the ones I’ve tried, even if some of them are rusty. And the darn thing still has the flour sifter intact! Do you know how rare that is? Most times someone has stripped it out to make more storage space. And it’s never been painted! Original oak. Someone really treasured this piece.”

She stepped back up to the cabinet and fiddled with the tambour door, a section that looked like the rolltop on a rolltop desk; it was near the porcelain work top and should have rolled up to reveal a storage area where glass spice jars, as well as baking tools and other cooking necessities, were kept. But the tambour would not budge. It was either jammed or broken, or moisture had caused the slats to swell, making them stick. That could be fixed, but it would temporarily keep her from finding out if it had more original parts hidden. “Isn’t it beautiful?” Jaymie said, glancing at her sister and stepping back so Becca could get a good look.

“That’s not what I was going to say, but … okay.”

“I’m going to bid on it,” Jaymie said, jotting down the lot number on her pad.

“What? Why?”

“Why?” Jaymie stuck the pad back in her purse and stared down at her older sister in disbelief. “Becca,

look

at it!”

“I am,” she said, eyeing it, a dubious expression on her round face. “It’s dirty and damaged. The side panels are chipped, the porcelain work top is scarred and the legs have water staining. It looks like crap. As far as vintage pieces go, I’d give this one a two out of ten.”

Jaymie marveled at how differently she and Becca could see things. Her sister was fifteen when Jaymie was born and almost seemed like a second mother at times; the message was always the same:

I am so much older than you,

she implied time and again,

that I know more and my ideas are better!

Becca was logical and pragmatic and had a numerical grading system for everything in life; two out of ten did not cut it. Anything worthwhile, from food to men to antiques, had to be a seven or better. Jaymie preferred to look beneath the surface to the heart of a piece, and this one had a heart of solid, twenty-four carat gold. “It just needs a little cleaning up. I love it, and I’m going to bid on it.”

“And put it where?” her older sister said, crossing her arms over her ample bosom, sensibly covered by a burgundy sweater to ward off the chill of approaching evening.

“I’m not sure yet,” Jaymie said, rubbing her bare arms. May in Michigan is changeable and moody, sun shining one moment and dark clouds scudding across the sky the next. Seduced by the heat of the late-afternoon sun, Jaymie had optimistically pulled her canvas sneakers out of the closet and had neglected to slip a sweatshirt or sweater over her pink T-shirt. The auction didn’t start until five p.m., and would likely run for hours; it would be dark and cold by the time they left, and she would be freezing. She shrugged, both at the cold and her sister’s gloomy assessment of the Hoosier. “I’ll find a place for it.”

“Jaymie, get real,” Becca said, still staring over the porch railing at her from the lawn. “The kitchen is packed enough as it is with all your crap. Vintage tins, old pots and pans, Pyrex bowls, bowls, bowls and more bowls

everywhere

! How many bowls can one cook use? The last thing we need is another big piece of furniture.”

“Do I call all your china and teacups

‘crap’

?” Jaymie shot back.

“My china and teacups are not cluttering the kitchen. I’m just saying there is no more room for another scrap of furniture or cooking junk!”

“You only live at the house every other weekend, so you don’t have to worry about it,” Jaymie said, going back to examining the Hoosier. Though they jointly owned the family’s nineteenth-century two-story yellow-brick home in Queensville, she was the only one who lived there full-time. It was truly a family heirloom, and had been deeded to Jaymie and Rebecca by their parents, Joy and Alan Leighton, who preferred the Florida heat and humidity to Michigan’s variable temperatures: too hot in summer, too cold and snowy in winter, and iffy in between.

“What do you think Mom would say about all that stuff crowding her kitchen?” Becca pointed out.

Jaymie sighed. Becca could be so controlling, a trait she had inherited from their mother. She thought—again, because she was so much older than Jaymie—she had a right to tell her sister what to do, but Jaymie was thirty-two, not ten, so the fifteen-year age gap was not such a big deal anymore. “Okay, first, it isn’t her kitchen. She always hated it anyway. Thank heavens she didn’t modernize it in the eighties when she wanted to.” She shuddered, and continued. “But I know exactly what she’d say:

‘Jaymie, you can’t possibly like all this clutter!’

She would mutter something about ‘hoarders,’ then Dad would tell her to butt out. It isn’t their house anymore, and they shouldn’t care one bit what I do to it.” She gave her older sister a defiant look.

Becca couldn’t deny that; though Joy Leighton had come to the home in Queensville as a young bride in the sixties, she had never been fond of the old yellow-brick house. In fact, when the Leightons did come back north, in the sultry heat of midsummer, they were more likely to stay at the family’s cottage on Heartbreak Island, the heart-shaped island in the middle of the St. Clair River between Queensville, Michigan, and Johnsonville, Ontario, the Canadian town named in honor of President Andrew Johnson, back in the eighteen hundreds.

Heartbreak Island, split in two by a navigable channel, was shared by American and Canadian cottagers, a compromise reached in the early eighteen hundreds to settle ongoing land disputes that lingered after the War of 1812. To Jaymie, that compromise was symbolic of the ongoing friendship between two sovereign nations that shared the world’s longest undefended border. In honor of that unique friendship, Queensville and Johnsonville shared holidays. This late-May Friday ushered in the first Canadian holiday weekend of summer, the Victoria Day weekend. On Sunday and Monday Canadian visitors would flock across the St. Clair River to Jaymie’s hometown—Queensville, Michigan, was named in honor of Queen Victoria—to attend the long-standing traditional “Tea with the Queen.”

But still, while Jaymie lived in Queensville year-round and adored her touristy little village home, Rebecca Leighton Burke ran her own company, RLB China Matching, out of her home in the nearby southwestern Ontario city of London, halfway along the highway between Detroit and Toronto and perfectly situated for business. She had settled there when she married a Canadian, and now, even after the divorce, stayed to look after their grandmother, who lived in London, too.

Becca bought and sold old bone china and made a good deal of money doing it. If someone had broken an antique Spode platter or Minton teacup, Becca could sell them a replacement … for a premium price. Perhaps it was unfair, as they shared ownership of the family home, but Jaymie felt that, since she was the one who cared for it most, she should be able to do what she wanted, as long as she consulted Becca on any substantial changes.

“Look, Jaymie, I can’t discuss this right now,” Becca said, her glance returning to the back lawn of the old house, where the flatbed stage was set; the nattily dressed gentleman auctioneer was mounting the steps as they spoke, so the auction must have been starting in minutes. She glanced down at her notebook and said, “I only came to tell you that I’ll be bidding on an assorted box of teacups and saucers—that’ll be for the Tea with the Queen fund-raiser Sunday and Monday, in case we run out—the complete set of Crown Derby, the Minton tea set, and the box of Spode completer pieces.” She checked each one off as she named it. She looked up at her sister with a worried frown. “Oh, and, uh, Joel and his new squeeze are here. I just thought I’d better warn you.” She began to walk away, but over her shoulder she threw, “And don’t you dare bid on that Hoosier!”

Jaymie stood frozen, her hand on the dusty porcelain work top of the cabinet, as she overlooked the green lawn, dotted with buyers and gawkers threading back through the tables of auction lots toward the stage. Joel was at the auction? And he was there with Heidi? Crap! As she stood there, silent, undecided on whether to flee or stay, she listened idly to a murmured conversation taking place around the corner of the old brick farmhouse, one of many, no doubt, as couples and groups decided on their bidding strategy.

“Look, I’ll bid on it,” a man said, “you just stay in the back and make sure no one

else

bids.”

“How am I going to do that?” a second voice asked.

“I don’t know! Be creative.”