Daily Life During the French Revolution (25 page)

Read Daily Life During the French Revolution Online

Authors: James M. Anderson

HOSPITALS

Of the 2,000 or so hospitals in France under the old

regime, some consisted of only one room staffed by a couple of nuns in a rural

village. Others were large public institutions like the

Hôtel-Dieu

in

Paris. By 1789, most major cities were equipped with a general hospital that

could attend to routine illnesses, as well as care for the elderly. Bordeaux

had seven hospitals of varying size and efficiency, and the facility in Paris

comprised a number of buildings. For many people, with no resources, these

disease-infested places, dreaded as the ultimate refuge, amounted to a dingy

and pathetic place to die.

Poor hygienic conditions and the failure to segregate those

with contagious diseases from people suffering from broken bones (although the

wealthy could obtain a separate room, since their good treatment augured well

for charitable donations) were the result of both lack of financial resources

and power struggles within the institutions.

Poor sanitary conditions were often aggravated by the fact

that many hospitals were situated on the edge of town next to cemeteries,

refuse dumps, and the municipal abattoir or close to fetid rivers and streams,

giving rise to humid and overpowering odors.

Daily life in the hospital often involved stormy sessions

between doctors and the nursing sisters. For instance, in 1785, at the

Hôtel-Dieu

in Montpellier, the royal inspector of hospitals and prisons, Jean

Colombier, insisted on the subordination of the sisters to the medical staff,

who accused the sisters, among other things, of overfeeding the patients. The

Mother Superior resigned because the doctors were given more sway than the

sisters in the internal affairs of the hospital. Championing better hygiene,

the doctors clashed with the sisters, and the struggle for supremacy became one

of traditional sympathy and consolation versus scientific and therapeutic

treatment. The management and the sisters both insisted that the hospital

should be a charitable institution, rather than a medical one. The

administration (made up of the city’s elite) preferred to see medical care

administered in the home and believed that the emphasis in the hospital should

be put on the spiritual and material wellbeing of the patients.

The buildings themselves were often in a sorry state of

disrepair. Frequently, the walls were crumbling, the roofs leaked, and broken

windows precariously adhered to rotting frames. The money for upkeep was not

always there, and the shortage grew worse throughout the eighteenth century.

The straw beds were breeding places for lice, fleas, and germs, and in summer

months, beds crawling with vermin became unbearable. Further, ventilation was

often poor, and the stench of urine and excretion was sometimes overwhelming.

Lack of hygiene in overcrowded rooms constituted an extreme health hazard in

many hospitals. Sometimes two or three people, each with different diseases,

might occupy the same bed, and straw was distributed around the floor for those

without a mattress to lie on. On occasion, a patient entered a hospital with

one ailment and contracted another there, one that could be fatal. Smallpox ran

through the children’s wards and led to many deaths. Tinea and scabies were

often endemic, typhus and dysentery were sometimes introduced, often by sick

soldiers, and gangrene, too, was a problem.

In winter, heat was precious, and lack of hot-water

bottles, foot warmers, and braziers meant that elderly patients developed

hypothermia and pneumonia. For young children and the elderly, the hospital was

too often the gateway to the grave.

As some progress was made in the understanding and control

of disease, most doctors became aware that good food and hygienic conditions,

as well as the isolation of patients with contagious diseases, played a part in

health. Such measures, however, were often sporadic, incomplete, and not

economically viable.

Conflict arose over the use of corpses for anatomical

research on the workings of the human body. This, along with teaching, was

firmly opposed by the sisters and the administration. When teaching was

allowed, procedural regulations were strict so as not to offend the sensitivity

of the nurses, who also felt that the sick and poor should not be molested by

students asking questions and trying to examine them.

The medical profession’s demands eventually convinced

hospital staff to allow some dissection of bodies, but, apart from executed

criminals, few bodies were procurable. In some instances, doctors, surgeons,

and medical students in private schools took liberties such as raiding

graveyards, often treating the remains in a cavalier manner once they had

finished their dissection. Body parts were dumped outside the cities in heaps

or thrown into a river, where bits might wind up at a public washing site.

As a result of the contentious situation, doctors vied with

one another to acquire posts in military garrisons, prisons, and the new

Protestant hospital in Montpellier, where they had direct access to the sick

without the obstructive influence of nursing sisters and administrators.

Whenever possible, people, even of modest means, avoided

hospitals; hospital admissions were usually not confidential, and the

experience was humiliating. Those who were desperate enough to enter the

General Hospital in Montpellier, for example, had to appear before the full

administration board of the institution, headed by the bishop, and a committee

of the city’s prestigious nobles. There, as often as not in rags, they pleaded

their case for acceptance. If they were admitted, their effects were

confiscated, their clothes taken to be washed and rid of fleas, while the

patient was examined by a student surgeon to ascertain if the illness was

genuine and that the patient was not suffering from any of the diseases that

were barred from the institution. If all was in order, the patient received a

kind of uniform from the nursing sister and was then sent to the hospital

chaplain for confession. Finally, the patient was ushered to a bed. With

thousands of dying old men and old women, babies, orphans, and handicapped and

deformed people, the hospitals gave an impression of a scene from hell.

By 1789, Paris was being cleaned up, and in the process the

establishment began to realize that mortality in cities was greater than that

in the country because the urban environment was so deleterious for its

inhabitants. Doctors agreed that a serious health risk was present because

people were forced to breathe air infected with the odor of bodies decaying in

the cemeteries, where they were often not properly buried, and by the open

sewers in the streets. Many houses still had chamber pots for toilets, and

these were emptied into the streets at night, giving the neighborhood an

insalubrious and disagreeable ambiance.

New graveyards were created outside the walls of the city,

but this met with opposition from those who wanted their loved ones buried

close by, and, in the end, burials continued in town for some time to come.

During the late eighteenth century, proper nourishing food

began to be a subject of discussion, along with the quality of the air. At

least for the wealthy, wholesome food and clean air were becoming priorities.

Concern was also expressed over the

Hôtel-Dieu

in Paris, whose humid and

airless interior gave rise to perpetual pestilence. Enlightened campaigns

advocated opening windows both in hospitals and in private homes to let fresh

air circulate.

Preoccupation with cleanliness within the city slowly began

to extend to concern for the cleanliness of the body; doctors started

encouraging people to wash themselves more frequently. Up to this time, little

or no attention had been paid to washing even excrement off the body.

Since the nuns were also in the business of making good

Christians out of the patients, many hospitals had chapels of their own or

altars in the rooms. Salaried priests kept track of death records and led the

sick in prayer, helped draw up wills, buried the dead, administered the

sacraments, catechized children, confessed new entrants, and said Masses for

benefactors. Sisters also watched over the patients at mealtimes to ensure that

there was no trafficking in food, no blasphemy, boasting, or inappropriate

conversation that reflected poorly on the hospital and the Catholic religion.

Sisters could impose rebukes and mild punishments, such as reducing rations or

short imprisonment. Serious matters of insubordination or discipline were taken

up by the administration board, and retribution could include corporal

punishment or banishment from the hospital.

Up to the middle of the eighteenth century, if a patient

under a doctor’s care died (as frequently happened), the cause was put down to

God’s will. Once the doctors were put in charge, however, they increasingly saw

disease as part of nature, unrelated to sin and God, and insisted on a secular

medical program set apart from the spiritual explanations of the church.

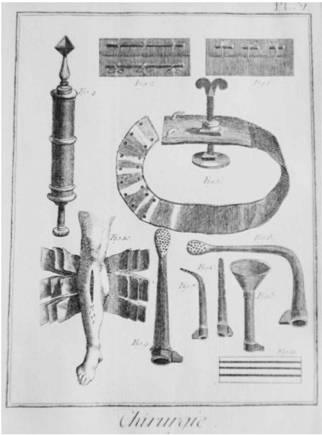

Surgical equipment ca. 1770, showing a wound compress

comprising a hooked leather strap, leg binding, and several other items.

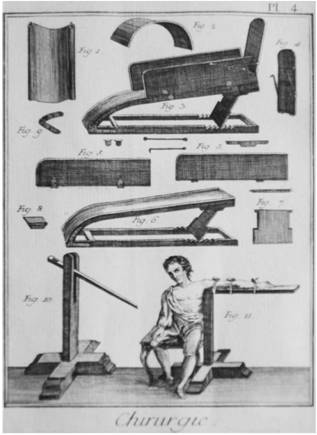

Surgical supports ca. 1770, including arm restraints

and an adjustable reclining seat, with diagrams of its various parts.

QUACKS AND CHARLATANS

The common people, superstitious and with a faith in

panaceas, were often beguiled by medical charlatans. The elixirs these

itinerant vendors offered might have been made of harmless vegetable juices and

herbs, but all were touted as a cure for most ailments.

Peddlers gathered crowds on street corners, extolling the

virtues of their product. Some, to attract people’s attention, supplied

entertainment: acrobats, jugglers, firework displays, dancers, musicians, and

tightrope walkers beckoned the curious. Markets, festivals, and fairs drew the

dissembling healer to put on his show and sell his concoctions. In one case,

Alexandre Cosne, son of a Parisian building worker, appeared with a huge pool

complete with mermaid, who answered questions from the crowd. Cosne would turn

up in cities claiming to be a magical healer whose potion would cure eye

ailments, skin disease, stomach problems, halitosis, and syphilis. It was also

touted as particularly effective for dyeing hair!

In Paris, the Pont Neuf, which spans the river Seine, was a

primary gathering point for swindlers, thieves, beggars, entertainers, and

other sundry people. Here there was someone to pull a rotten tooth, make

eyeglasses, or fit an ex-soldier with a wooden leg. There were those who sold

powdered gems guaranteed to beautify the face, drive away wrinkles, and add to

longevity.

MIDWIVES

An integral component in the lives of the French were the

midwives who assisted in the delivery of children. They generally lacked any

formal education, especially in rural areas, but as good Catholics they could

be relied on by the state and the church under the old regime to record the

births and to report those to unmarried mothers. Midwives were usually

middle-aged and often widowed women who used their skills in childbirth to help

make ends meet by charging a small fee. In the 1780s, they began to receive a

little technical training at state expense in a number of dioceses, and they

could receive a diploma of competence from their local guild of surgeons after

a six-month course at the

Hospice de la Maternité

in Paris. Few attended

these classes, however. After the revolution, the government attempted to

extend its control over midwives when the medical establishment complained that

they were very ignorant and illiterate and in many cases did not understand the

French language. Government agents weeded out the most incompetent but realized

that to ban all who were unqualified would essentially eliminate their

function. Those who had won the confidence of local inhabitants were allowed to

carry on.