Daily Life During the French Revolution (9 page)

Read Daily Life During the French Revolution Online

Authors: James M. Anderson

REVOLUTION AND THE ECONOMY

Figures show that the total value of the country’s trade in

1795 was less than half what it had been in 1789; by 1815, it was still only 60

percent of what it had been at the beginning of the revolution.

More than any other class of people, perhaps, the

manufacturers felt the effects of the revolution the most profoundly. The

rivalry with English textile makers, strong in 1787 and 1788; the revolutionary

movement in 1789 in which so many landlords, clergy, and those in public

employment lost income; the emigration of the wealthy classes, causing

unemployment for many others; the falling value of the assignats—all combined

to lower purchasing power and industrial output. Those whose investments were

safe nevertheless restricted their buying and hoarded their money, apprehensive

about the unsettled state and the prospect of civil war. The result was,

predictably, immense unemployment and a starving population, especially in the

big cities.

On December 29, 1789, Young visited Lyon and conversed with

the citizens. Twenty thousand people were unemployed, badly fed by charity;

industry was in a dismal state; and the distress among the lower classes was

the worst they had ever experienced. The cause of the problem was attributed to

stagnation of trade resulting from the emigration of the rich. Bankruptcies

were common.

The Constituent Assembly’s economic reforms were guided by

laissez-faire doctrine, along with hostility to privileged corporations that

resembled too much those of the old regime. The Assembly wanted to make

opportunities accessible to every man and to promote individual initiative. It

dismantled internal tariffs, along with chartered trading monopolies, and

abolished the guilds of merchants and artisans. Every citizen was given the

right to enter any trade and to freely conduct business. Regulation of wages

would no longer be of government concern, nor would the quality of the product.

Workers, the Assembly insisted, must bargain in the economic marketplace as

individuals; it thereby banned associations and strikes. Similar precepts of

economic individualism applied to the countryside. Peasants and landlords were

free to cultivate their fields as they liked, regardless of traditional

collective practices. Communal traditions, however, were deep-seated and

resistant to change.

The Atlantic and Mediterranean port cities, all centers of

developing capitalist activity, had suffered from anti-federalist repression

and from English naval blockades. In textile towns such as Lille, the decline

was abrupt and ruinous. No matter what business they were in, tailors,

wigmakers, watchmakers—all those engaged in businesses related to deluxe items

or pursuits—lost their clientele. Even shoemakers suffered along with other

lower-class enterprises, except for the very few who managed to get contracts

to supply the military. In heavy industry such as iron and cannon manufacture,

some opportunities were provided by the continuing warfare, which tended to

focus capital and labor on the provision of armaments. For most businesses,

however, the situation appeared gloomy.

In 1790, while in Paris, Young learned that the cotton

mills in Normandy had stood still for nine months. Many spinning jennies had

been destroyed by the locals, who believed they were Satan’s invention and

would put them out of work. Trade, Young said, was in a deplorable condition.

All cities were in a sad state and remained so throughout

the revolutionary period. When Samuel Romilly returned to Bordeaux in 1802,

during a period of peace with England, he was grieved to see the silent docks

and the grass growing long between the flagstones of the quays. The sugar trade

with the West Indies continued to flourish, but in port cities connected to the

slave trade, people were alarmed over talk in the National Convention about

freeing the blacks, who provided the labor for the colonial sugar industry.

THE ASSIGNAT

Preceding the revolution, the basic money of account was

the livre, of which three made an écu, and 24 livres equaled one louis. The

livre was made up of 20 sous (the older term was sols), and the sous was

divided into 12 deniers. (The system was similar to that used in

England—pounds, shillings, and pence—until the 1970s.)

On December 19, 1789, to redeem the huge public debt and to

counterbalance the growing deficit, the revolutionary Constituent Assembly

issued treasury notes or bonds called assignats, to the amount of 400 million

livres distributed in 1,000-livre notes. These were intended as short-term

obligations pending the sale of confiscated lands formerly owned by the

nobility and the church and were distributed to creditors of the state to be

exchanged for land of equal value or redeemed at 5 percent interest. The

assignats were then to be liquidated, reducing government debt. Neither the

economy nor the royal tax revenues increased as quickly as the deputies had

hoped; assignats were made legal tender in April 1790, and subsequent issues

bore no interest.

In the autumn of 1790, the government issued another 400

million in assignats. In following years, more and more were issued in smaller

denominations of 50 livres, then 5 livres, and, finally, 10 sous. By January

1793, about 2.3 billion assignats were in circulation. The paper currency

rapidly became inflated, and people hoarded metallic coins that had been used

previously. By July 1793, a 100-livre note was only worth 23 livres.

The stringent financial measures put in place during the

Terror temporarily stabilized the value of the assignat at one-third of its

face value. However, by early 1796, under the Directory, inflation again

increased dramatically, and the assignats in circulation were worth less than 1

percent of their original value. This did not even cover the cost of printing

them. Severe inflation stopped only when all paper currency was recalled and

redeemed at the rate of 3,000 livres in assignats to one franc in gold. On May

21, 1797, all unredeemed assignats were declared void.

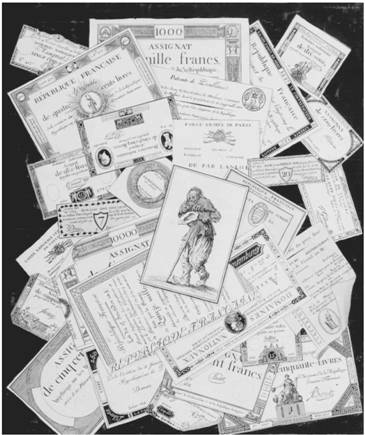

The value of the assignats depreciated rapidly. The

beggar symbolizes the subsequent ruin of thousands of investors.

TAXATION

The company Farmers-General purchased the privilege of

collecting taxes and paying state debts for the various government departments.

Taxes thus passed through private hands, and some of it wound up in private

pockets. There was no central bank to provide economic stability, only a group

of businessmen who sought to find the best balance between a functioning government

and their own profits. The tax farmer advanced a specified sum of money to the

royal treasury and then collected a like sum in taxes. Given exceptional powers

to collect the money, tax farmers bore arms, conducted searches, and imprisoned

uncooperative citizens. The money collected over and above that specified in

the contract with the government went to the tax farm. Tax farmers were usually

rich men and hated by the general public.

There were various kinds of taxes levied in different parts

of the country. The taille was a direct tax collected on property and goods;

the clergy and the nobility were exempt from this levy, and the peasants bore

the brunt. Indirect taxes included the

gabelle

, or salt tax, a duty on

tobacco, the aides, which were excise duties collected on the manufacture,

sale, and consumption of a commodity, and the traites, customs duties collected

internally. There was no uniformity, and some sections of the country bore

heavier tax burdens than others. The main direct tax, the taille, was levied by

the crown on total income in the northern provinces but only on income from

landed property in the south.

SALT TAX

The government monopoly on salt went back as far as the

thirteenth century; the salt was extracted from seawater ponds that were left

to dry out. The detested salt tax (

gabelle

) had become a leading source

of royal income and was levied at different rates in various parts of the

country. In some regions, everyone over eight years of age was required to

purchase seven kilos of salt each year at a fixed government price. In other

regions, people were required to purchase a fixed quantity of salt per

household. There were other areas where the salt tax did not apply (

pays

exempt

), such as the Basque country and Brittany. Fortunes were made in the

illegal transport of salt.

The collectors and enforcers of the salt tax were often

crude, abusive men who were allowed to carry arms and to stop and search

whomever they pleased. They were not above looking for contraband by squeezing

the choicest parts of women who had no recourse but to suffer the humiliation.

Women sometimes did hide bags of salt in corsets and other places where they

hoped not to be squeezed; some concealed it in false rears of their dresses.

Salt rebellions were frequent, and battles sometimes erupted between smugglers

and tax collectors.

The Loire River was notorious for the movement of

contraband, since it separated tax-free Brittany from heavily taxed Anjou; the

price for salt was 591 sous per minot (49 kilos) in Anjou but 31 sous in

Brittany, which was exempt from the tax thanks to an agreement reached with the

crown when Brittany became part of France. The large number of families working

the salt ponds there were in the best position to ferry the salt across the

river, so the government passed a no-fishing-at-night law to curb the illegal

trade and stationed troops along the banks of the river in an attempt to end

the smuggling. The

gabelle

was abolished by the revolution but was

reinstated 15 years later; it continued in force until 1945.

3 - TRAVEL

At

the end of the Seven Years War, swarms of English people visited France, and

some left accounts of their travels there. Later, hostilities between France

and England during the American War of Independence nearly dried up the flow of

English tourists to Paris and the provinces, but it still did not stop

entirely, and the return to peace in 1783 brought another influx of Britons to

French shores.

Travelers to France, especially those from England, were

always surprised by the great distances and the plethora of internal customs

houses. Further, they found that there was no national language either spoken

or understood by a great many of the illiterate inhabitants and no uniform

system of administration, laws, taxes, weights and measures.

Although French people did not seem to travel much within

their own country, those who did, with interests different from those of

foreign visitors, have also left accounts that help portray the daily life of

the time. About half of the members of the Convention were sent out on

assignments to the departments (administrative districts) or to the army, and

some reports of their missions are available. For many, such as a

representative from Paris, a journey to the south was like going to a foreign

land.

MODES OF TRANSPORT

Major rivers in France, such as the Seine, Loire, Saône,

Rhône, and Garonne, had long been used as a means of transportation. To

supplement the river system and move cargo, some important canals were built in

the seventeenth century, including the Brienne, Orléans, and Languedoc. The Canal

du Midi, running from Toulouse to Béziers, made it possible to link the

Atlantic Ocean with the Mediterranean through southwest France. One could

travel on riverboats pulled by horses along the banks that in Paris embarked

from the Palais Royal or the bridge of Saint Paul. Arrangements for private

travel on commercial barges or riverboats over long distances seemed not to

appeal to many who, for whatever reason, preferred to go by horse and carriage.

For this manner of travel, the transportation system was in place, with

scheduled stops and prices. One could, for example, go to the Royal General

Bureau of Coaches and Freight and book a trip to anywhere in the realm.

By the late eighteenth century, the region of the Ile de

France had the best-constructed roads in Europe, greatly admired by foreigners.

However, when traveling by horse drawn vehicles over large distances, travelers

found that the roads sometimes became just bumpy tracks and that the journey

was slow and tedious. Going to Bordeaux or Strasbourg from Paris took six days;

traveling to Toulouse took seven or eight days, and to Marseille, nine days.