Daily Life in Elizabethan England (11 page)

Read Daily Life in Elizabethan England Online

Authors: Jeffrey L. Forgeng

Thomas Dekker,

The Batchelar’s Banquet

(London: T. C., 1603), sig. B3r.

Households and the Course of Life

45

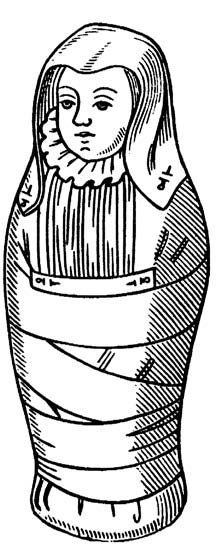

An infant in swaddling clothes. [Clinch]

apostle spoons,

having the image of one of the 12 apostles at the end of the handle, were a common choice, as were other gifts of pewter and silver.

Baptism was not only a religious ritual. In the 16th century, to belong to society and to belong to the church were considered one and the same, so that the ceremony of baptism also marked the child’s entry into the social community. In fact, the modern birth certificate has its counterpart in the baptismal record entered into the parish register: the law required the child’s name and date of baptism to be recorded in the register as a part of the ceremony; this record served as a legal verification of that person’s age and origin for the rest of their life.

At the core of the baptismal ceremony was the assigning of a name. The surname was inherited from the child’s father. Given names were mostly drawn from traditional stock, but there was more scope for variation than had been the case in the Middle Ages. Perhaps the most common were French names imported during the Middle Ages. For boys, these included (in roughly descending order of popularity) William, Robert, Richard, Humphrey, Henry, Roger, Ralph, Fulk, Hugh, and Walter. Girls’ names in this category included Alice, Joan, Jane, Isabel, Maud, Juliana, Eleanor, and Rose. Some French names had been imported more recently, such as Francis for boys and Joyce, Florence, and Frances for girls.

46

Daily Life in Elizabethan England

Also popular were the names of saints. Among boys, some of the most common saints’ names were (roughly in descending order of popularity) John, Thomas, James, and George. Behind these came Peter, Anthony, Lawrence, Valentine, Nicholas, Christopher, Andrew, Giles, Maurice, Gervase, Bernard, Leonard, and Ambrose. Female saints’ names included Catherine, Elizabeth, Anne, Agnes, Margaret (with its variant, Margery), Lucy, Barbara, and Cecily. The name Mary was also used, although it was much less common than on the Continent. Because Protestantism discouraged the veneration of saints, these names had lost much of their religious significance and were more likely to be chosen simply on the basis of family traditions.

Another religious source of names was the Old Testament, from which came such boys’ names as Adam, Daniel, David, Toby, Nathaniel, and Zachary. Obscure Old Testament names were especially popular among the more extreme Protestant reformers. For girls, Old Testament names were rarer, although one occasionally finds a Judith. The names Simon and Martha derived from the New Testament.

A few names derived from Greek or Latin, such as Julius, Alexander, Miles, and Adrian for boys, Dorothy and Mabel for girls. Some names were ultimately inherited from the Anglo-Saxons, such as Edward and Edmund for boys, Edith, Winifred, and Audrey for girls. A few names were taken from legend. For boys these included Arthur, Tristram, Lance-lot, Perceval, and Oliver. For girls the principal example is Helen or Ellen.

Among Puritans there was a growing fashion for creative names with religious themes, such as Flee-Sin and Safe-on-High. By and large, the upper classes and townspeople were most likely to be innovative in naming their children; country folk were likely to use more traditional names.

Then as now, people were often known by shortened forms of their

names, many of which are still in use today. Edward might be known as Ned, John as Jack, David as Davy, Robert as Robin, Dorothy as Doll, Mary as Moll, Catherine as Kate or Kit.

A few weeks after the christening, the mother would go to the church for the ceremony called churching. This had originated in the Middle Ages as a purifying ritual, but in Protestant England it was reinterpreted as an occasion for thanksgiving, both for the safe delivery of the child and for the mother’s survival of the dangers of childbirth. Churchings were popular social occasions among women.

Childhood

Childhood was a dangerous time in Elizabethan England. The infant

mortality rate may have been about 135 in 1,000, and in some places as high as 200 in 1,000. By comparison, a mortality rate of 125 in 1,000 is exceptionally high in the modern developing world; the rate in the United States is around 10 in 1,000. Between the ages of 1 and 4, the mortality rate

Households and the Course of Life

47

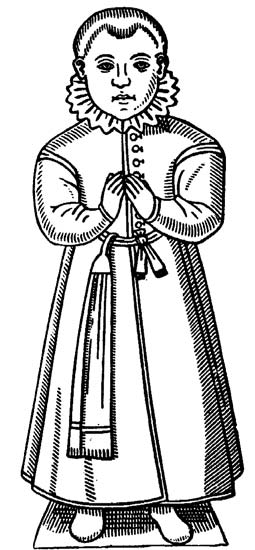

A boy wearing a gown. [Clinch]

was around 60 in 1,000, and about 30 in 1,000 between the ages of 5 and 9.

This means that out of every 10 live births, only 7 or 8 children lived to 10

years of age. The high mortality rate was primarily due to disease. Young children have weak immune systems, and the illnesses that send countless modern children to the emergency room in the middle of the night often ended fatally for their Elizabethan counterparts.3

It is sometimes supposed that because of the high mortality rate, parents were reluctant to invest emotion in their children, but evidence suggests that love was considered an essential component in the parent-child relationship. The sentiments expressed by Sir Henry Sidney in a letter to his son were not at all uncommon:

I love thee, boy, well. I have no more, but God bless you, my sweet child, in this world forever, as I in this world find myself happy in my children. From Ludlow Castle this 28th of October, 1578. [Addressed:] To my very loving son, Robert Sidney, give these. Your very loving father.4

Parents were expected to be strict, but this was seen as a sign of love.

Children who were not disciplined properly would not learn how to

interact with the rest of society: as one Elizabethan proverb has it, “Better unfed than untaught.” Undoubtedly there were cruel parents who abused

48

Daily Life in Elizabethan England

their power, but there is no evidence to indicate that abusiveness was any more common then than now, and child abuse could be prosecuted in the courts.

For the first six years or so, the Elizabethan child would be at home and principally under female care. Most children were cared for by their own mothers, although privileged children might be in the keeping of a nurse.

Young babies were kept in cradles fitted with rockers to help soothe the child to sleep; sometimes they slept in bed with their parents—this could be risky to the child, but it simplified midnight nursing and was probably especially beneficial on cold winter nights.

Old cloths were used as diapers. The baby’s head was kept warm with a cap called a

biggin,

and its body was wrapped in bands of linen called

swaddling.

Theorists believed that swaddling kept the limbs straight so that they would grow properly, but more importantly, it kept the baby warm and controlled its mobility: as the infant grew, unsupervised freedom could be extremely dangerous in a home with open fireplaces and countless other domestic dangers.

Babies were breast-fed and might be nursed in this way for about one or two years—Elizabeth herself had been weaned at 25 months. Aristocratic children often received their milk from a wet nurse, sparing the mother the trouble of nursing, and also raising the aristocratic birth-rate, since she would cease lactating and become fertile once more. The wet nurse was always a woman of lower social standing, and by definition one who had recently given birth herself, so that she was giving milk. With the high rate of infant mortality, there were many poor women able to earn a bit of extra money for a time by nursing someone else’s child.

As the child grew, it would be swaddled less restrictively to allow the arms to move, and eventually the swaddling would be dispensed with in favor of a long gown (allowing easy access to the diaper cloths). The child’s gown was typically fitted with long straps that dangled from the shoulders. The straps probably derived from the false sleeves sometimes found on adults’ gowns, but with children they allowed the garment to double as a harness. Boys and girls alike were dressed in gowns and petticoats akin to the garments of adult women; only after age 6 or so were boys

breeched

—put into the breeches worn by adult men.

For Elizabethan children, like children today, the early years were primarily a time for play and learning. During this time children would explore their world and begin to acquire some of the basic tools of social interaction.

Elizabethan English

The first of these tools was the child’s mother tongue. Elizabethan En glish was close enough to modern English that it would be comprehensible to us today. The main differences in pronunciation were in a few of

Households and the Course of Life

49

the vowels:

weak,

for example, rhymed with

break

, and

take

sounded something like the modern-English

tack.

As in most modern North American accents,

r

’s were always pronounced. Overall, Elizabethan English would most resemble a modern Irish or provincial English accent; the pronunciation associated with Oxford and Cambridge, the BBC, and the royal family is a comparatively recent development. There was considerable difference in pronunciation from one place to another. The dialect of London was the most influential, but there was no official form of the language, and even a gentleman might still speak his local dialect: a biographer in the 1600s noted that Sir Walter Raleigh “spoke broad Devonshire to his dying day.”5

Etiquette

In learning the language, the child would also learn the appropriate modes of address, which were more complex than they are today. For example, the word

thou

existed as an alternative to

you.

To us it sounds formal and archaic, but for the Elizabethans it was actually very informal, used to address a person’s social inferiors and very close friends. You might call your son or daughter

thou,

but you would never use it with strangers (

thee

stood in the same relationship to

thou

as

me

to

I

—“Thou art a fine fellow,” but “I like thee well”).

The child would also have to learn the titles appropriate to different kinds of people. As a rule, superiors were addressed by their title and surname, inferiors by their given name. If you were speaking to someone of high rank or if you wished to address someone formally, you might call them

sir

or

madam

; you would certainly use these terms for anyone of the rank of knight or higher. As a title,

Sir

designated a knight (or sometimes a priest) and was used with the first name, as in Sir John.

More general terms of respect were

master

and

mistress.

These could be simply a polite form of address, but they were particularly used by servants speaking to their employers, or by anyone speaking to a gentleman or gentlewoman. They were also used as titles, Master Johnson being a name for a gentleman, Master William a polite way of referring to a commoner. Commoners might also be called

Goodman

or

Goodwife,

especially if they were at the head of a yeomanly household. Ordinary people, especially one’s inferiors, might be called

man, fellow,

or

woman.

Sirrah

was applied to inferiors and was sometimes used as an insult. A close friend might be called

friend, cousin,

or

coz.

The child would have to learn the etiquette of actions as well as of words.

Elizabethan manners were no less structured than our own, even if their provisions seem rather alien in some respects. The English commonly kissed each other as an ordinary form of greeting, although the practice declined in the first half of the 1600s. In greeting someone of higher social status, a person was expected to

make a leg

—performing a kind of bow—