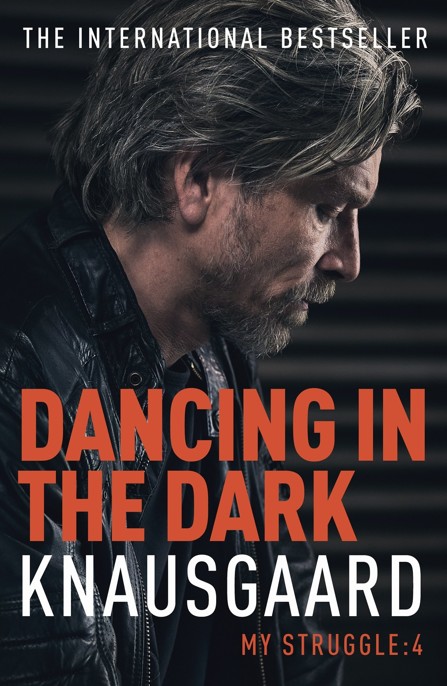

Dancing in the Dark: My Struggle Book 4

Read Dancing in the Dark: My Struggle Book 4 Online

Authors: Karl Ove Knausgaard

Tags: #Literature & Fiction, #Contemporary, #Genre Fiction, #Biographical, #Family Life, #Literary, #Contemporary Fiction, #Literary Fiction

Contents

A Time to Every Purpose Under Heaven

A Death in the Family: My Struggle Book 1

A Man in Love: My Struggle Book 2

Boyhood Island: My Struggle Book 3

My Struggle: Book 4

SLOWLY MY TWO

suitcases glided round on the carousel in the arrivals hall. They were old, from the end of the 1960s, I had found them among mum’s things in the barn when we were about to move house, the day before the removal van came, and I immediately commandeered them, they suited me and my style, the not-quite-contemporary, the not-quite-streamlined, which was what I favoured.

I stubbed the cigarette out in the ashtray stand by the wall, lifted the cases off the carousel and carried them to the forecourt.

It was five minutes to seven.

I lit another cigarette. There was no hurry, there was nothing I had to do, no one I had to meet.

The sky was overcast, but the air was still sharp and clear. There was something alpine about the landscape even though the airport I was standing outside was only a few metres above sea level. The few trees I could see were stunted and misshapen. The mountain peaks on the horizon were white with snow.

Just in front of me an airport bus was quickly filling up with people.

Should I catch it?

The money dad had so reluctantly lent me for the journey would tide me over until I got my first wage in a month’s time. On the other hand, I didn’t know where the youth hostel was, and wandering blindly around an unfamiliar town with two suitcases and a rucksack would not be a good start to my new life.

No, better take a taxi.

Apart from a short walk to a nearby snack bar stand, where I consumed two sausages with mashed potato in a cardboard tray, I stayed in the youth hostel room all evening, lying with the duvet over my back and listening to music on my Walkman while writing letters to Hilde, Eirik and Lars. I started one to Line as well, the girl I had spent all summer with, but set it aside after one page, undressed and switched off the light, for all the difference that made, it was a light summer night, the orange curtain glowed in the room like an eye.

Usually I would fall asleep at once wherever I was, but on this night I lay awake. In only four days’ time I would be starting my first job. In only four days’ time I would be entering a classroom in a small village on the coast of Northern Norway, a place I had never been and knew nothing about, I hadn’t even seen any pictures.

Me!

An eighteen-year-old Kristiansander, who had just finished

gymnas

, who had just moved away from home, with no experience of working other than a few evenings and weekends at a parquet flooring factory, a bit of journalism on a local paper and a month at a psychiatric hospital this summer, I was about to become a form teacher at Håfjord School.

No, I couldn’t sleep.

What would the pupils think of me?

When I went into the classroom for the first lesson and they were sitting there on their chairs in front of me, what would I say to them?

And the other teachers, what on earth would they make of me?

A door was opened in the corridor, releasing the sound of music and voices. Someone walked along quietly singing. There was a shout: ‘Hey, shut the door.’ Afterwards all the noise was enclosed again. I rolled over onto my other side. The strangeness of lying in bed under a light sky must have played a part in my not being able to fall asleep. And once the thought was established that it was difficult to sleep, it became impossible.

I got up, pulled on my clothes, sat in the chair by the window and began to read.

Dead Heat

by Erling Gjelsvik.

All the books I liked were basically about the same topic.

White Niggers

by Ingvar Ambjørnsen,

Beatles

and

Lead

by Lars Saabye Christensen,

Jack

by Alf Lundell,

On the Road

by Jack Kerouac,

Last Exit to Brooklyn

by Hubert Selby, Jr.,

Novel with Cocaine

by M. Agayev,

Colossus

by Finn Alnæs,

Lasso round the Moon

by Agnar Mykle,

The

History of Bestiality

trilogy by Jens Bjørneboe,

Gentlemen

by Klas Östergren,

Icarus

by Axel Jensen,

The Catcher in the Rye

by J. D. Salinger,

Humlehjertene

by Ola Bauer and

Post Offic

e by Charles Bukowski. Books about young men who struggled to fit into society, who wanted more from life than routines, more from life than a family, in short, young men who hated middle-class values and sought freedom. They travelled, they got drunk, they read and they dreamed about their life’s Great Passion or writing the Great Novel.

Everything they wanted I wanted too.

The great longing, which was ever-present in my breast, was dispelled when I read these books, only to return with tenfold strength the moment I put them down. It had been like that all the way through my latter years at school. I hated all authority, was an opponent of the whole bloody streamlined society I had grown up in, with its bourgeois values and materialistic view of humanity. I despised what I had learned at

gymnas

, even the stuff about literature; all I needed to know, all true knowledge, the only really essential knowledge, was to be found in the books I read and the music I listened to. I wasn’t interested in money or status symbols; I knew that the essential value in life lay elsewhere. I didn’t want to study, had no wish to receive an education at a conventional institution like a university, I wanted to travel down through Europe, sleep on beaches, in cheap hotels, or at the homes of friends I made on the way. Take odd jobs to survive, wash plates at hotels, load or unload boats, pick oranges . . . That spring I had bought a book containing lists of every conceivable, and inconceivable, kind of job you could get in various European countries. But all of this was to culminate in a novel. I would sit writing in a Spanish village, go to Pamplona and run the bulls, continue on down to Greece and sit writing on one of the islands and then, after a year or two, return to Norway with a novel in my rucksack.

That was the plan. That was why I didn’t do my military service when

gymnas

was over, like so many of my school friends had done, nor did I enrol at university, as the rest had done, instead I went to the employment office in Kristiansand and asked for a list of all the teaching vacancies in Northern Norway.

‘Hear you’re going to be a

teacher

, Karl Ove,’ people I met at the end of the summer said.

‘No,’ I answered. ‘I’m going to be a writer. But I have to have something to live off in the meantime. I’ll work up there for a year, put some money aside and then travel down through Europe.’

This was no longer an idea in my head but the reality I was in: tomorrow I would go to the harbour in Tromsø, catch the express boat to Finnsnes and then the bus south to the tiny village of Håfjord, where the school caretaker would be waiting to welcome me.

No, I couldn’t sleep.

I took the half-bottle of whisky from my suitcase, fetched a glass from the bathroom, poured, drew the curtain aside and took a first shivering sip as I gazed at the strangely light housing estate outside.

When I woke at ten-ish the following morning my nerves were gone. I packed my things, rang for a taxi from the payphone in reception, stood outside with my suitcases at my feet and smoked as I waited. This was the first time in my life I had travelled anywhere without having to return. There was no ‘home’ to return to. Mum had sold our house and moved to Førde. Dad lived with his new wife further north, in Northern Norway. Yngve lived in Bergen. And, as for me, I was on my way to a first flat of my own. There I would have my own job and earn my own money. For the very first time I had control of all the elements in my life.

Oh, how bloody fantastic it felt!

The taxi came up the hill, I threw the cigarette end to the ground, trod on it and placed the cases in the boot, which the driver – a plump elderly man with white hair and a gold necklace – had opened for me.

‘The harbour, please,’ I said, getting in at the back.

‘Harbour’s big,’ he said, turning to me.

‘I’m going to Finnsnes. On the express boat.’

‘We can fix that for you, no problem.’

He set off downhill.

‘Are you going to the

gymnas

there?’ he asked.

‘No,’ I said. ‘I’m going on to Håfjord.’

‘Oh yes? Fishing? You don’t look like a fisherman, I must say!’

‘Actually, I’m going there to teach.’

‘Oh, right. Right. There are so many southerners who do that. But aren’t you terribly young to have a job like that? You have to be eighteen, don’t you?’

He laughed and looked at me in the mirror.

I gave a short laugh too.

‘I left school in the summer. I reckon that’s better than nothing.’

‘Yes, I’m sure it is,’ he said. ‘But think of the kids growing up there. Teachers straight from

gymnas

. New ones every year. No wonder they pack school in after the ninth class and go fishing!’

‘Yes, I suppose it isn’t very surprising,’ I said. ‘But it’s hardly my fault.’

‘No, not at all. And fault? Who’s talking about blame! Fishing’s a much better life than studying, you know! Far better than sitting and studying until you’re thirty.’

‘Yes. I’m not going to study.’

‘But you’re going to be a teacher!’

He looked at me in the mirror again.

‘Yes,’ I said.

There was silence for a few minutes. Then he took his hand off the gear stick and pointed.

‘Down there, that’s your express boat.’

He stopped outside the terminal, set my cases on the ground and closed the boot again. I gave him the money, not knowing what to do about a tip, I had been dreading this the whole journey and solved the problem by saying that he could keep the change.

‘Thank you!’ he said. ‘And good luck!’

Bye bye, fifty kroner.

As he rejoined the road I stood counting the money I had left. I didn’t have much, but I could probably get an advance, surely they would understand that I wouldn’t have any money

before

the job started?

With its one main street, numerous plain concrete buildings, probably hastily erected, and its barren environs girdled by mountain ranges in the distance, Finnsnes, it struck me a few hours later, sitting in a patisserie with a cup of coffee in front of me and waiting for the bus to leave, looked more like a tiny village in Alaska or Canada than Norway. There wasn’t much of a centre, the town was so small that everything had to be considered the centre. The atmosphere was quite different here from in the towns I was used to, because Finnsnes was so much smaller, of course, but also because no effort had been made anywhere to make the place look attractive or homely. Most towns had a front and a back, but here everything looked pretty much the same.

I leafed through the two books I had bought in the nearby shop. One was called

The New Water

by a writer unfamiliar to me, Roy Jacobsen; the other was

The Mustard Legion

by Morten Jørgensen, who had played in a couple of the bands I had followed a few years ago. Perhaps it hadn’t been such a good idea to spend my money on them, but after all I was going to be a writer, it was important to read, if only to see how high the bar was set. Could I write like that? This was the question that kept running through my brain as I sat there flicking through the pages.

Then I ambled over to the bus, had a last smoke outside, put my cases in the luggage compartment, paid the driver and asked him to tell me when we were in Håfjord, walked down the aisle and sat on the penultimate seat on the left, which had been my favourite for as long as I could remember.

Across from me sat a lovely fair-haired girl, perhaps one or two years younger than me, she had her satchel on the seat, and I imagined she went to the

gymnas

in Finnsnes and was on her way home. She had looked at me when I got onto the bus, and now, as the driver shifted into first gear and pulled away from the stop with a jerk, she turned to look at me again. Not lingeringly, no more than a glance, and barely a fleeting one at that, but still it was enough to give me a stiffie.

I put on my headset and inserted a cassette into the Walkman. The Smiths,

The Queen is Dead

. So as not to appear intrusive, I concentrated on staring out of the window on my side for the first few kilometres and resisted all impulses to look in her direction.

After passing through a built-up area, which began as soon as we left the centre and extended for quite a distance, where around half the passengers got off, we came to a long deserted straight stretch. Whereas the sky above Finnsnes had been pale, covering the town beneath with its vapid light, here the shade of blue was stronger and deeper, and the sun hanging over the mountains to the south-west – whose low but steep sides obscured a view of the sea that had to be there – caused the red-flecked, in places almost purple, heather which grew densely on either side of the road to glow. The trees here were for the most part deformed pines and dwarf birches. On my side the green-clad mountains the valley rose up to meet were gentle, hills almost, while those on the other were steep and wild and alpine, although of no great height.