Danubia: A Personal History of Habsburg Europe (47 page)

Read Danubia: A Personal History of Habsburg Europe Online

Authors: Simon Winder

Tags: #History, #Europe, #Austria & Hungary, #Social History

Switzerland came and went in its impact on Europe, with its mercenaries severely mauled in the Italian Wars, but the associated Three Leagues (the League of the Ten Jurisdictions, the Grey League and the splendidly named League of God’s House) to the east of the Confederation caused intermittent violent chaos into the seventeenth century, driving various military commanders into total mental breakdowns by their sheer obduracy and localism. It was only the arrival of Napoleon that ended their independence and folded them into Switzerland.

The Habsburgs were always confounded by the way that while mountains are excellent defences they are also extremely difficult to defend. The Carpathians, as became clear in war after war well into the twentieth century, look like a terrific natural bastion on a map but each pass is sufficiently far from the next that they were hard to reinforce and could therefore turn into the worse kind of static fortress, soaking up troops and supplies while the enemy simply goes round the corner and does something else. In the First World War one of the most depressing experiences (in a crowded category) of the Austro-Hungarian army was the 1915–16 defence of the Carpathians, which had seemed smart on paper, but proved impossible for the usual reason – that so few people live in the mountains because there are so few supplies and they get covered in snow for half the year. The result was thousands of deaths from the cold and a total collapse in the survivors’ morale.

The Habsburg cult of the mountains and of mountain folklore in fact had military origins. As so few people could live in the mountains there was (if they were not wiped out by fire, flood or slave-raiding) an excess population each year – classically split between women who would work as servants and men who would join the army. Stefan Zweig’s story ‘Leporella’ is the perfect exposition of the fate of women – the Tyrolean girl who ends up in Vienna working for a worthless and libertine nobleman with catastrophic results. Virtually the entire course of Habsburg military literature is filled with tough Slovak, Ruthene or Serb squaddies, assigned by their German or Magyar officers the same sort of ‘martial virtues’ the British projected onto the Highland Scots, Sikhs or Jats. The Habsburgs had also always used large formations of irregular troops, drawn in many cases from the Dinaric Alps and festooned in outlandish hats, boots and jackets. This gave the Habsburg military an entirely different profile to western European formations. The Military Frontier districts guarding the Empire against the Ottomans also had many regular troops, but it was groups such as the mainly Croat Pandurs who became famous, with a romantic cult quite at odds with the realities of border atrocity warfare. Many of these highly decorative irregulars were at such key events as the relief of Vienna in 1683. Given that a vital element in the Allied force there was a mass of Polish hussars with high, feathered wings on their armour and that they were fighting Ottoman camel troops in coloured turbans, the whole thing must have looked like a fancy-dress party or circus parade gone very badly wrong.

This fascination with exotic folk costume readily shifted, as the army’s clothing became more regularized and banal, into a more general curiosity about those parts of the Empire that still maintained forms of folk dress. The same forces that created railways, accurate long-range rifles and mass colour printing in the mid-nineteenth century also created both nationalism and a civilian cult of folk costume: as millions of peasants flooded into the Habsburg cities, as multicoloured, easily spotted uniforms were put away and as mass literacy became available, real folk costume vanished for most people but became enshrined in other ways.

It is impossible to exaggerate the importance of folklore to the emergent nationalisms. In the search for authentic new heroes, there was both a military thread and an outlaw or bandit thread, where a motley selection of figures who had stood up to authority became enshrined in countless rhymes, songs, tales and portraits, with their folk costume (often a blind guess, of course – even the figure himself often had a shaky real historical existence, let alone his clothing) a symbol of integrity in the face of besuited German or Hungarian oppression. Everywhere had a bandit king – Juraj Jánošík, friend to the Slovaks and Gorals, or Oleksa Dovbush, scourge of the Poles and friend of the Ruthenes and Hutzuls, now a major Ukrainian hero whose attractive Carpathian rock hideaway I hiked through recently.

The Hungarians themselves were torn on this issue – they wished to distance themselves from Germanizing greyness, but also wanted to appear progressive and modern. Indeed all nationalist groups became irreparably tangled up on this point and could never decide whether rows of girls waving hoops covered in flowers or rows of men in steel helmets and puttees were the way ahead. In the end they settled for both. There is a particularly shrill cartoon by the Slovenian artist Hinko Smrekar which brings the folk costume question to its acme. Drawn in 1918 it shows Woodrow Wilson standing next to a piece of meat-grinding equipment and shoving into the machine a grotesque crone labelled Old Europe, vampire-toothed, skeletal and in a dirty wig, a crucifix around her neck, holding a gallows and whip. As she disappears into the machinery out of the bottom bursts a group of very fit-looking young women in folk dress, dancing away and helpfully labelled as Yugoslavia, Czechoslovakia and Poland, with an unidentified further figure with earrings and dark, curly hair which I would guess might be the spirit of Questionable Additional Lands Grabbed by Romania.

CHAPTER ELEVEN

The Temple to Glorious Disaster

»

New Habsburg empires

»

The stupid giant

»

Funtime of the nations

»

The deal

»

An expensive sip of water

The Temple to Glorious Disaster

Vienna’s Military History Museum was Franz Joseph’s pride and joy. In many ways it brackets perfectly the entire Habsburg experience, defined by two huge hunks of metal: a fifteenth-century ‘supergun’ from Styria of staggering size and impracticality

1

and an armoured cupola from a Belgian fort devastated in 1914 by a twentieth-century supergun, the Škoda heavy siege mortar. This cupola was somehow hauled to the museum across hundreds of miles as a tribute to Austro-Hungarian engineering and industrial prowess and to show its loyalty to and value to its German ally, shortly before all such concerns became nugatory.

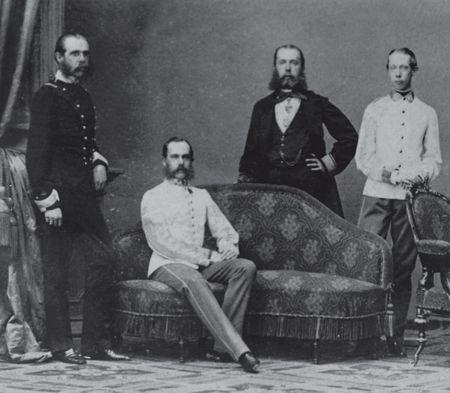

The museum was built as part of the Arsenal complex in south-east Vienna, one of a series of Imperial urban strongpoints packed with weapons that could quell a future 1848 – a role they were never called on to fulfil. Designed quite arbitrarily in a sort of Moorish style more associated with harems than soldiers, it is one of the first examples (and a relatively charming one) of the sort of brain-destroying architectural eclecticism which would wound and goad generations of Habsburg intellectuals and designers into finally giving birth to modernism. Franz Joseph was deeply engaged in every aspect of the building and it was set up as a temple to the greatness of the Habsburg military traditions. The entrance way is crowded with life-size white marble statues of generals – many of them prime figures in the Habsburg cult of victory followed by defeat, making the entire hall into a sort of Temple to Glorious Disaster. The beards, ruffs, tricornes and weapons change but the outcome tended to be the same. At the head of the main staircase there is a bust of the young Franz Joseph with

Kaisertreu

written under it – the conventional term describing the unquestioning loyalty and adulation felt by the soldiers for their supreme commander. As all these very boringly conceived statues were carved and hauled into place through the 1850s and 1860s this was a sentiment that was to be put under considerable pressure, and more than a few senior officers must have given a derisive ‘Ha!’ as they walked past the Kaisertreu bust.

It has always been important to the British to think of the nineteenth century as broadly peaceful once Napoleon had been finally defeated, with the Crimean War as an exception plus a couple of ‘cabinet wars’. An air of slight stuffiness hangs over much of the century, but in practice Europe was just as turbulent as in the twentieth century, albeit with an incomparably lower death toll. The British are among the most egregious fantasists, as their Victorian peacefulness only existed by pretending that the dozens of colonial wars in which they were engaged were not happening. Indeed, the near universal habit of seeing European and colonial wars as unrelated is unfortunate, as in practice it was just as dangerous to be a ruler targeted for destruction in Europe as it was to be one in India or Africa. If there had been a suitable venue, figures as diverse as the King of Hannover, the last Mughal Emperor, the Duke of Modena and the Nawab of Oudh could have had bitter conversations about the fickle nature of the mid-nineteenth century.

Austrian policy was fiendishly difficult. With the crushing of the Hungarian rebellion there seemed to be a possibility of great things, and indeed for short periods the Empire had a quite extraordinary reach, both in its own right and on behalf of the German Confederation, the loose association of German states of which Austria was the most senior member. At one point during the Schleswig-Holstein crisis in the 1860s the Habsburg navy was in the North Sea, engaged in the Battle of Heligoland with the Danish navy and, following defeat, taking refuge in the waters of the British naval base on Heligoland. The very idea of a British base just off the German coast (soon to be swapped in fact with Germany for Zanzibar), let alone Habsburg warships being in the North Sea, let alone fighting the Danes, seems scarcely imaginable, but this was part of a crisis that dominated Europe. In a similar moment of glory Habsburg troops occupied the mouths of the Danube at the outbreak of the Crimean War, creating a buffer between the Russians and the Ottomans. For a couple of years it seemed that a Habsburg fantasy going back at least two centuries was about to be realized with the entire river system under Vienna’s rule, but none of the other powers thought this a good idea and with the end of the war the soldiers were obliged humiliatingly to back out and make way by the end of the decade for a united Romania, a nightmare far worse for Vienna than somnolent Turkish rule.

In the end none of the opportunities came off and the period from 1849 to final humiliation in 1866 was catastrophic for the Habsburgs – but catastrophic in an annoying way, as so many of the problems stem from a mulish failure by Franz Joseph and his advisers ever to do anything right. It would be far too complicated and tiresome to give all the details of the congresses, treaties, meetings between monarchs and armistices that stud the period. Places which have never before or since been important suddenly took on a world-historical role. I have a friend who used for family reasons to have to go to the western Schleswig coast for Christmas and, not speaking German let alone dialect, he was obliged for a few days, as gales howled over the dunes and the tiles rattled on the roof of the farmhouse kitchen, to listen to his wife’s relatives at mealtimes collapse with laughter – while he munched his way through the usual burnt pig selections and potatoes – as they came up with incomprehensible but clearly ever more elaborate insulting terms to describe him. Schleswig has featured in almost no conversation before or since the 1860s, but at this one moment in time, across Europe there was a sudden rush to atlases. Statesmen would narrow their eyes, stare at some imagined horizon, puff out their chests and claim some overwhelming, scarifying national interest in places with barely any population or even any animals.

The extreme instability of the period came from the collapse of the semi-solidarity of Europe’s rulers following the 1848 revolutions. Suddenly a policy of mere reaction seemed untenable, not least because of the arrival of the Emperor Napoleon III in France, the great lord of misrule in this period and as creatively damaging in his way as Bismarck was to be. It was the Habsburgs’ disaster to suddenly appear, at different times and in different constellations, a backward and unhelpful element in the European system. This was most clearly shown in the Crimean War, where Britain and France uneasily allied themselves against Russia in a bid to protect the Ottoman Empire from further predation. The Austrians owed the Russians everything for their help in defeating the Hungarians, but now, only four years later, they found themselves siding with the Allies out of fear of Russian ambition to take over Moldavia and Wallachia from the Ottomans and thereby block the Danube. Franz Joseph was in an impossible position – he moved his troops into Transylvania in a threatening manner, forcing the Russians to keep an army on the border which would have been useful elsewhere, but then could not make up his mind to attack. The Russians were half mad with rage over this betrayal and their recent and useful alliance with the Austrians was at an end. In happier times, a grateful Franz Joseph had given a statuette of himself to his best friend Tsar Nicolas. Nicolas now took the statuette off his desk and gave it to his valet.