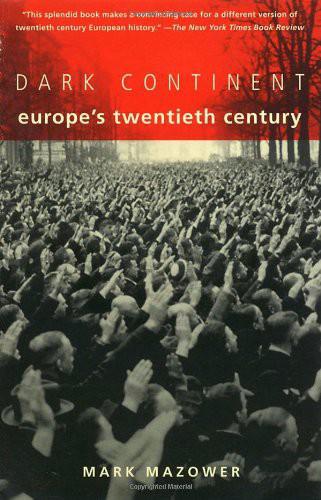

Dark Continent: Europe's Twentieth Century

Read Dark Continent: Europe's Twentieth Century Online

Authors: Mark Mazower

Tags: #Europe, #General, #History

ACCLAIM FOR

MARK MAZOWER’s

DARK CONTINENT

“Compelling.… A lively account of Europe in the twentieth century.”

—

The Wall Street Journal

“Fine and fascinating.… Mazower uses his considerable skills to look deep into the heart of European darkness, and he does not flinch from what he finds.”

—

Chicago Tribune

“Mark Mazower has provided a rich mixture in his highly individual and intelligent interpretation of Europe’s twentieth-century history.”

—

The Times Literary Supplement

“Mazower has written a timely, argumentative, and ultimately optimistic book; he is particularly good at illuminating the substance of beliefs beneath ideologies.”

—

The New Yorker

“An absorbing and challenging history of Europe in the twentieth century.… [Mazower] is a skilled analyst and persuasive writer.”

—

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

“Fascinating.…”

—

The Washington Times

MARK MAZOWER

DARK CONTINENT

Mark Mazower has taught at the University of Sussex and Princeton, and is Professor of History at Birkbeck College, University of London. He is the author of the prize-winning

Inside Hitler’s Greece: The Experience of Occupation, 1941–1944

.

ALSO BY

MARK MAZCWER

Greece and the Inter-War Economic Crisis

Inside Hitler’s Greece:

The Experience of Occupation, 1941–44

Copyright © 1998 by Mark Mazower

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions.

Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Random House, Inc.,

New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited,

Toronto. Originally published in hardcover in Great Britain by Allen Lane/

The Penguin Press, an imprint of the Penguin Group, London and

subsequently in hardcover in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf,

a division of Random House, Inc., New York, in 1998.

Vintage and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to the following for permission to

reprint previously published material:

Harcourt Brace & Company: Map, “The Expulsion of Germans from Central Europe, 1945–1947,” from

Europe in the Twentieth Century

, 2nd ed., by Robert O. Paxton, copyright © 1985 by Harcourt Brace & Company. Reproduced by permission of the publisher. Helicon Publishing Limited: Two maps, “Retreat of Ottoman Power in Europe” and “Russia in the Great War,” from

The History of Europe

by J. M. Roberts, copyright © 1996 by Helicon Publishing Limited. Reproduced by permission of the publisher. Penguin Books Limited: Map, “The Multinational Empire, 1878–1916,” from

The Hapsburgs: Embodying Empire

by Andrew Wheatcroft (Viking, 1995), copyright © 1995 by Andrew Wheatcroft. Reproduced by permission of the publisher. The University of Chicago Press: Table 2.1, “Foreign Population in Selected European Countries,” from

Limits of Citizenship

by Yasemin Nuhoglu Soysal, copyright © 1994 by The University of Chicago Press. Reproduced by permission of the publisher.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the Knopf edition as follows:

Mazower, Mark.

Dark Continent: Europe’s twentieth century / Mark Mazower.—1st American ed.

p. cm.

1. Europe — History — 20th century. I. Title. II. Series.

D424.M39 1998

940.55 — DC21 98–15886

eISBN: 978-0-307-55550-2

Author photograph © by Johanna Weber

v3.1

for Ruthie

And In Memory Of

Frouma Mazower Max

Mazower

Reg Shaffer

CONTENTS

Cover

About the Author

Other Books by This Author

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Preface

1. The Deserted Temple: Democracy’s Rise and Fall

2. Empires, Nations, Minorities

3. Healthy Bodies, Sick Bodies

5. Hitler’s New Order, 1938–45

6. Blueprints for the Golden Age

8. Building People’s Democracy

9. Democracy Transformed: Western Europe, 1950–75

10. The Social Contract in Crisis

11. Sharks and Dolphins: The Collapse of Communism

Maps and Tables

Notes

Guide to Further Reading

PREFACE

Why then do the European states claim for themselves the right to spread civilization and manners to different continents? Why not to Europe itself?

Europe may seem to be a continent of old states and peoples, yet it is in many respects very new, inventing and reinventing itself over this century through often convulsive political transformation. Some nations—such as Prussia—have been wiped off the map in living memory; others—like Austria or Macedonia—are less than three generations old. When my grandmother was born in Warsaw, it was part of the Tsarist empire, Trieste belonged to the Habsburgs and Salonika to the Ottomans. The Germans ruled Poles, the English Ireland, France Algeria. The closest much of Europe came to the democratic nation-state which has become the norm today were the monarchies of the Balkans. Nowhere did adults of both sexes have the vote, and there were few countries where parliaments prevailed over kings. In short, modern democracy, like the nation-state it is so closely associated with, is basically the product of the protracted domestic and international experimentation which followed the collapse of the old European order in 1914.

The First World War mobilized sixty-five million men, killed over eight million and left another twenty-one million wounded; it swept away four of the continent’s ancient empires and turned Europe into what Czech politician Thomas Masaryk described as “a laboratory

atop a vast graveyard.” “The World War,” wrote Russian artist El Lissitsky, “requires us to test all values.” Amid the ruins of the

ancien régime

—with the Kaiser exiled, the Tsar and his family shot—politicians promised the masses, enfranchised and mobilized as never before, a fairer society and a state of their own. The liberal Woodrow Wilson offered a world “safe for democracy”; Lenin a communal society emancipated from want and free of the exploitative hierarchies of the past. Hitler envisaged a warrior race, purged of alien elements, fulfilling its imperial destiny through the purity of its blood and the unity of its purpose. Each of these three rival ideologies—liberal democracy, communism and fascism—saw itself destined to remake society, the continent and the world in a New Order for mankind. The unremitting struggle between them to define modern Europe lasted most of this century.

2

In the short run, both Wilson and Lenin failed to build the “better world” they dreamed of. The communist revolution across Europe did not materialize, and the building of socialism was confined to the Soviet Union; the crisis of liberal democracy followed soon after as one country after another embraced authoritarianism. By the late 1930s the League of Nations had collapsed, the Right was ascendant, and Hitler’s New Order looked like Europe’s future. Against the liberal defence of individual liberties the Nazis counterposed the racial welfare of the collectivity; against liberalism’s doctrine of the formal equality of states it offered Darwinian struggle and rule by racial superiors; against free trade it proposed the coordination of Europe’s economies as a single unit under German leadership. Yet how bewilderingly fast fortunes changed in the struggle of ideologies. In the 1940s—the century’s watershed—the Nazi utopia reached its zenith, and then as swiftly collapsed. Fascism became the first major ideology to suffer conclusive defeat at the hands of the history it claimed to have mastered.

In the long run, the 1940s were important for another reason too. The exhausting, murderous experience of total war—the culmination of nearly a century of imperial and national struggles inside and outside the continent—led to a growing weariness with ideological politics across the continent. The great tide of mass mobilization began to ebb, and with it the militarism and collectivism of the inter-war years.

Believers became cynics at worst, at best apathetic, resigned and domesticated. People rediscovered democracy’s quiet virtues—the space it left for privacy, the individual and the family. Thus after 1945, democracy re-emerged in the West, revitalized by the challenge of war against Hitler, newly conscious of its social responsibilities. Only now it faced competition from the Left not the Right, as the Red Army, having crushed Nazi Germany’s imperial dreams, brought communism to the new Soviet empire in eastern Europe.

Although the Cold War represented the last stage of the ideological struggle for Europe’s future, it differed crucially from earlier phases in its avoidance of real war—at least on the continent itself. To be sure there were crises; but in general, the two superpowers lived in “peaceful coexistence,” aiming at each other’s ultimate demise, but accepting each other’s right to exist in the present for the sake of continental stability and peace. The two systems armed themselves for a war that could not be fought, and competed to provide welfare for their citizens, and to bring economic growth and material prosperity. Both offered some astonishing initial achievements; but only one proved capable of adapting to the growing pressures of global capitalism. With the collapse of the Soviet empire in 1989, not only the Cold War but the whole era of ideological rivalries which began in 1917 came to an end.