Dark Eminence Catherine De Medici And Her Children (6 page)

Read Dark Eminence Catherine De Medici And Her Children Online

Authors: Marguerite Vance

silver, to be drawn by six white horses, all part of her royal equipment. She laid her cheek against that of the gentle white palfrey standing patiently awaiting her praise. He blew softly through velvety nostrils and she laughed at the tiny tickling hurricane against her ear, appraising meanwhile the housings of heavily embroidered damask fringed in silver tagged with medallions of fine enamel.

oo

Another day, with her seven-year-old sister Marguerite bouncing happily along beside her, she followed two of her serving women up and down one of the long corridors of the Louvre palace while they opened chest after chest containing the heavy silver and gold plate for her household use, unlocked coffers filled with exquisite linens and hangings for her bedchamber and presence chamber.

"Methinks, sister/' Marguerite chuckled, "you'll live in many, many palaces to use all these soft furnishings, albeit they're so lightly wrought they'll not endure long/'

She would always chuckle and bounce, this youngest daughter of Catherine de Medici, until in old age she died more or less an outcast from her own family.

King Philip, on a diplomatic mission in the Netherlands, was unable to come to Paris so he appointed Don Fernando Alvarez de Toledo, Duke of Alba, to act as his representative at the marriage; and on June 19th he and his party arrived. They were welcomed with great fanfare at the Louvre and there are many charming stories about the meeting of the Duke and Princess Elizabeth. He knelt to kiss the hern of her robe and then presented her with the Kings gift, an ivory casket of jewels, among them a superb miniature of

the King himself set in diamonds and fastened to a delicate chain to be worn as a necklace.

It is said the Princess blushed, then turned deathly white as the Duke read to her the King s ardent note—in Spanish-accompanying the gift. Then, in a gesture which may have been rehearsed, she pressed the miniature to her lips.

The following day the betrothal of Elizabeth to King Philip was celebrated in the great hall of the Louvre. The contract of betrothal was signed and rings were exchanged. Only the marriage ceremony itself remained to make Elizabeth Queen Consort of Spain. Two days later, on June 21st, on a platform of state erected before Notre Dame Cathedral the vows were spoken; solemnly, pompously for Philip by Alba; distinctly, though scarcely above a whisper, by the lovely bride.

In her fabulous gown of cloth of gold under a mantle of blue velvet she was truly a fairy-tale princess. Many rinses had restored her dark hair to its natural color and where it escaped from the heavy, caplike crown of jewels above it, it clustered about her brow, accentuating the ivory whiteness of her skin, its delicate perfection. From her neck were suspended King Philip's miniature and the most prized of all the crown jewels of Spain, a great, pear-shaped pearl known as La Pelegrina.

Mary Stuart had been a beautiful bride, but Elizabeth glowed with a kind of inner radiance. Her dark eyes beheld the world about her with a glowing serenity in their depths, and if terror and a persistent premonition of misfortune set her young body shivering beneath its weight of priceless

fabrics, no one knew. Indeed, the Duke of Alba's fastidious notions were so completely satisfied that he was heard to exclaim in frank delight, "Of a surety the truly royal graces of this august princess will wipe forever from His Majesty's heart all grief he may yet feel for his former consort."

After the marriage ceremony, the feasting, the hall and the masques, the new Queen of Spain and her mother retired to her apartments, preceded by her torch bearers and pages, and her bridegroom-by-proxy left for the suite assigned the royal party in the Hotel Villeroy.

With curtains drawn against any possible breath of sweet June night air, half smothered in layer on layer of heavy, jewel-encrusted fabrics, Elizabeth lay staring into the darkness. No air penetrated the curtained bed where the cloth of gold and silver and the folds and ruffles of metallic lace gave off a bitter odor, and the young Queen wearily reviewed her mother's long lecture. Her pillow encased in Holland cloth heavily embroidered in Spanish work of black and gold thread chafed her neck, and the sheet, folded back over the velvet coverlet and similarly embroidered, rubbed her warm wrists. Exhausted with the day's long ceremonies, bewildered by the new honors bestowed on her and the exacting requirements of Spanish etiquette, turn as she would, she could find no relief from the suffocating heat. Trying to concentrate, she went over and over Queen Catherine's words:

"Remember," the mother drove the point home, "you are Queen of Spain now, the mightiest kingdom in the world, and if you are wise and act carefully you can do untold good wherever and whenever you choose. I shall send messages

constantly," she continued, "to advise and help you. Spain and France are now united as His Majesty, your liege lord, becomes my son. Never forget, dear child, you have two loyalties now: Spain and the House of Hapsburg and France and the House of Valois. Bear in mind, Elizabeth, strategy, diplomacy; these must be your guides henceforth. Listen well and speak not hastily or lightly lest your words confound and confuse and betray you. . . ."

There was a great deal more but the tired girl found she could not listen any longer. Possibly Catherine sensed her weariness and called for her women. Now, hours later, try as she would, Elizabeth could remember almost nothing of her mother s long harangue. Finally, in a burst of unbearable discomfort, she flung back the velvet coverlet. Her heavy white satin night shift clung to her in slippery, clammy folds and she shook them in a half-hearted hope of relief from the heat. From far, far away somewhere came the sounds of shouting, shrieking laughter, the thump of tabors, the rasping disharmony of rebec, pipe and trumpet played by revelers unsure of their notes. So the wedding feast continued through the night; so, worn out, Elizabeth, Queen of Spain, fell asleep.

Henry II of France was just forty years old. The rather dull-looking young bridegroom of Catherine de Medici twenty-six years earlier had outgrown much of his phlegmatic attitude toward life. At forty he was a lithe, athletic figure, fond of gaiety and sports, kindly and far too generous for his own good or that of his kingdom. He was of medium

Dark Eminence

height, with a strong, slender nose, dark eyes and hair and the neat, pointed moustache and beard of his day.

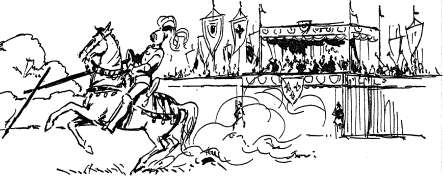

On the day following the wedding His Majesty was in high spirits. Here was a negotiation that had terminated exactly as he had hoped it would. A five-year truce between Spain and France would be followed by more treaties which, in his present mood, he felt sure would be equally satisfactory. So ran his thoughts as the Marshal de Vieileville buckled him into his armor preparatory to entering the lists for the jousting which was to be the principal entertainment of the day. Though no one suspected it, it was destined to be the last tournament to be held at the French Court.

A roar of applause greeted Henry as he rode out into the arena. He saluted the gallery where Catherine, the Queen Dauphiness, and Elizabeth were seated, then he whirled to meet his first adversary, the Duke of Savoy. The Duke was soon to marry the King's sister and the two men encountered each other in a spirit of laughing camaraderie. Both lances

Two Brides

61

were broken though neither man was unseated, and the applause was redoubled. Next Henry challenged the Duke of Guise who, wily diplomat that he was, permitted the King to carry off the honors. The clamor grew; the hot afternoon throbbed with it as the air thickened with dust, and in the heart of Elizabeth the premonition of impending disaster mounted.

Henry now sent for a young Scottish guardsman, a Captain Montgomery, noted for his skill in the jousts, and commanded him to run against him. Catherine, uneasy at the King's determination to continue the tournament which by all odds he had already won, sent him a note begging him to stop. "Have done, my lord," she wrote. "The honors already are yours and the day is over. Have done, I pray you."

But Henry was in no mood to stop now. "By my faith as a true knight," he cried, "I have scarcely loosed my limbs! Bring me another lance to break before we depart!"

Montgomery demurred for he knew his own skill; he

realized the King must be tiring in his heavy armor, and he dreaded the results to the King s dignity and to his own life should he unhorse him. However, he had no choice but to accept the challenge.

A hush, almost as though the spectators were holding their collective breath, hung over the field as the two knights took their positions, then came thundering toward each other on either side of the low barrier. Faster, faster, their long lances at the ready, they came; then with a clash that ripped the scorching air like the sound of a giant knife cutting steel, lance and armor met.

Both lances were broken but, to the horror of those watching, the King swayed in the saddle, slumped forward over the head of his mount and would have fallen but for attendants who ran to his aid. He was carried to his pavilion where it was found that a fragment of Montgomery's lance somehow had entered the visor of the King s helmet, striking the eye and penetrating deep into the brain.

Weeping, Montgomery knelt beside him, begging that his right hand be severed. But the King, in agony, absolved him of any blame, saying he had acted with knightly valor and in obedience to a command. Henry then was moved to the palace of Les Tournelles on the outskirts of Paris, a comparatively small palace which he loved, and there the Court surgeons did all they could to save the life of their sovereign. Not even Catherine might enter the sickroom just yet, its door guarded by a grim-faced old soldier who had served his king well across the years, Anne de Montmorency, Constable of France and Grand Master of the Household.

The days of suffering for the wounded monarch dragged into a week, then a few more days, and on the 30th of June, 1559, Henry of Valois, Henry II of France, died and the unwieldy crown of France passed from his steady head to the wavering one of his son, Francis.

Chapter 5 LONG JOURNEY

AMONG the great families of sixteenth-century France the Guises stood out as warriors and astute politicians. Their roots were deep in the soil of Lorraine, the name Guise an adoption by the younger generation. There were seven brothers, clever adventurers all, whose cleverness had carried them into the councils of the Crown itself. Francis I, dying, had begged Henry, his son, to be wary of the Guises, warning that they would "strip him and his children of their doublets and his people of their shirts/'

Henry II, however, had found them wonderfully helpful in many ways, especially the eldest, Francis, Duke of Guise, and his next younger brother, Charles, Cardinal of Lorraine. Without quite realizing how it had come about so quickly, Henry saw the Dauphin, Francis, married to Mary Stuart, a daughter and granddaughter of Guises; and his little daugh-

ter, Claude, married to the Duke of Lorraine, another Guise.

Now with Henry in his tomb at Saint-Denis, Catherine brooded on the influence the mighty Guises would have on the weak young King, how far they would dare go in wresting the control of his capricious will from her, his mother, who had always ruled him—and all her children.