Darwin's Dangerous Idea (57 page)

Read Darwin's Dangerous Idea Online

Authors: Daniel C. Dennett

300 BULLY FOR BRONTOSAURUS

Tinker to Evers to Chance

301

But modern punctuationalism

—

especially in its application to the va-are much more complete and three-dimensional than fossils usually are, and

garies of human history

—

emphasizes the concept of contingency: the

their classification by Charles Walcott early in this century was guided by his

unpredictability of the nature of future stability, and the power of

literal dissection of some of the fossils. He shoehorned the varieties he found

contemporary events and personalities to shape and direct the actual

into traditional phyla, and so matters stood (roughly) until the brilliant

path taken among myriad possibilities.

reinterpretations in the 1970s and 1980s by Harry Whittington, Derek Briggs,

—STEPHEN JAY GOULD 1992b, p. 21

and Simon Conway Morris, who claimed that many of these creatures—and they are an astonishingly alien and extravagant lot—had been misclassified; Gould speaks here not just of unpredictability but of the power of con-they actually belonged to phyla that have no modern descendants at all, phyla temporary events

and personalities

to "shape and direct the actual path" of never before imagined.

evolution. This echoes exactly the hope that drove James Mark Baldwin to That is fascinating, but is it revolutionary? Gould (1989a, p. 136) certainly discover the effect now named for him:

somehow

we have to get person-thinks so-. "I believe that Whittington's reconstruction of

Opabinia

in 1975

alities—consciousness, intelligence, agency—back in the driver's seat. If we will stand as one of the great documents in the history of human knowledge."

can just have contingency—radical contingency—this will give the

mind

His trio of heroes didn't put it that way (see, e.g., Conway Morris 1989), and some elbow room, so it can

act,

and be

responsible

for its own destiny, their caution has proven to be prophetic; subsequent analyses have tempered instead of being the mere effect of a mindless cascade of mechanical pro-some of their most radical reclassincatory claims after all (Briggs et al. 1989, cesses! This conclusion, I suggest, is Gould's ultimate destination, revealed in Foote 1992, Gee 1992, Conway Morris 1992). If it weren't for the pedestal the paths he has most recently explored.

Gould had placed his heroes on, they wouldn't now seem to have fallen so I mentioned in chapter 2 that the main conclusion of Gould's

Wonderful L

far—the first step was a doozy, and they didn't even get to take the step for

ife: The Burgess Shale and the Nature of History

(1989a ) is that if the tape of themselves.

life were rewound and played again and again, chances are mighty slim that But in any case, what was the revolutionary point that Gould thought was

we

would ever appear again. There are three things about this conclusion that established by what we may have learned about these Cambrian creatures?

have baffled reviewers. First, why does he think it is so important?

The Burgess fauna appeared suddenly ( and remember what that means to a (According to the dust jacket, "In this masterwork Gould explains why the geologist), and most of them vanished just as suddenly. This nongradual diversity of the Burgess Shale is important in understanding this tape of our entrance and exit, Gould claims, demonstrates the fallacy of what he calls past and in shaping the way we ponder the riddle of existence and the

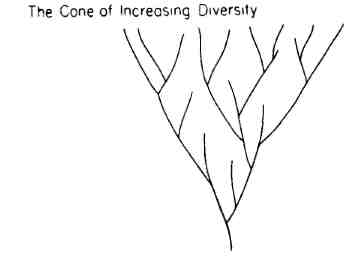

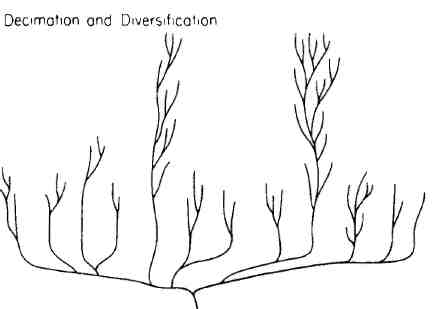

"the cone of increasing diversity," and he illustrates his claim with a re-awesome improbability of human evolution.") Second, exactly what

is

his markable pair of trees of life.

conclusion—in effect, who does he mean by "we"? And, third, how does he A picture is worth a thousand words, and Gould emphasizes again and again, think this conclusion (whichever one it is) follows from his fascinating with many illustrations, the power of iconography to mislead even the expert.

discussion of the Burgess Shale, to which it seems almost entirely unrelated?

Figure 10.12 is another example, and it is his own. On the top, he tells us, is We will work our way through these questions from third to second to first.10

the old false view, the cone of increasing diversity; on the bottom, the Thanks to Gould's book, the Burgess Shale, a mountainside quarry in improved view of decimation and diversification. But notice that you can turn British Columbia, has now been elevated from being a site famous among the bottom picture into a cone of increasing diversification by simply paleontologists to the status of an international shrine of science, the birth-stretching the vertical scale. (Alternatively, you can turn the top picture into a place of ... well, Something Really Important. The fossils found there date new and approved icon of the bottom sort by squeezing the vertical scale from the period known as the Cambrian Explosion, a time around six hun-down, in the style of standard punctuated-equilibrium diagrams—e.g., on the dred million years ago when the multicellular organisms really took off, right in figure 10.6.) Since the vertical scale is arbitrary, Gould's diagrams creating the palm branches of the Tree of Life of figure 4.1. Formed under don't illustrate any difference at all. The bottom half of his lower diagram perfectly illustrates a "cone of increasing diversity," and who knows whether peculiarly felicitous conditions, the fossils immortalized in the Burgess Shale the very next phase of activity in the top diagram would be a decimation that turned it into a replica of the bottom diagram. The cone of increasing diversity is obviously not a fallacy, if we measure diversity by the number of different 10. Yes, I know, Joe Tinker played shortstop, not third base, but cut me a little slack, please!

species. Before there were a hundred species there were ten, and before there were ten there were two, and so

302 BULLY FOR BRONTOSAURUS

Tinker to Evers to Chance

303

new kingdoms!—have to start out as mere new subvarieties and then become new species. The fact that from today's vantage point they appear to be early members of new

phyla

does not in itself make them special at all. They

might

be special, however, not because they were "going to be" the founders of new phyla, but because they were

morphologically

diverse in striking ways. The way for Gould to test this hypothesis would be, as Daw-kins (1990) has said, to "take his ruler to the animals themselves, unprejudiced by modern preconceptions about 'fundamental body plans' and classification. The true index of how unalike two animals are is how unalike they actually are!" Such studies as have been done to date suggest, however, that in fact the Burgess Shale fauna, for all their peculiarity, exhibit no inexplicable or revolutionary morphological diversity after all (e.g., Con-way Morris 1992, Gee 1992, McShea 1993).

The Burgess Shale fauna were, let us suppose (it is not really known), wiped out in one of the periodic mass extinctions that have visited the Earth.

The dinosaurs, as we all know, succumbed to a later one, the Cretaceous Extinction (otherwise known as the extinction at the K-T boundary), probably triggered about sixty-five million years ago by the impact of a huge asteroid. Mass extinction strikes Gould as very important, and as a challenge to neo-Darwinism: "If punctuated equilibrium upset traditional expectations (and did it ever!), mass extinction is far worse" (Gould 1985, p. 242 ). Why?

According to Gould, orthodoxy requires "extrapolationism," the doctrine that all evolutionary change is gradual and predictable: "But if mass extinctions are true breaks in continuity, if the slow building of adaptation in normal times does not extend into predicted success across mass extinction boundaries, then extrapolationism fails and adaptationism succumbs" (Gould The cone of increasing diversity. The false but still conventional iconography of 1992a, p. 53). This is just false, as I have pointed out: the cone of increasing diversity, and the revised model of diversification and decimation, suggested by the proper reconstruction of the Burgess Shale. [Gould 1989a, I cannot see why any adaptationist would be so foolish as to endorse p. 46.]

anything like "extrapolationism" in a form so "pure" as to deny the pos-FIGURE 10.12

sibility or even likelihood that mass extinction would play a major role in pruning the tree of life, as Gould puts it. It has always been obvious that the it must be, on every branch of the Tree of Life. Species go extinct all the most perfect dinosaur will succumb if a comet strikes its homeland with a time, and perhaps 99 percent of all the species that have ever existed are now force hundreds of times greater than all the hydrogen bombs ever made.

extinct, so we must have plenty of decimation to balance off the

[Dennett 1993b, p. 43.]

diversification. The Burgess Shale's flourishing and demise may have been less gradual than that of other fauna, before or since, but that does not Gould responded (1993e) by quoting a passage from Darwin himself, clearly demonstrate anything radical about the shape of the Tree of Life.

expressing extrapolationist views. So is adaptationism (today ) committed to Some say this misses Gould's point: "What is special about the spectacular this hopeless implication? Here is one instance when Charles Darwin himself diversity of the Burgess Shale fauna is that these weren't just new

species,

but has to count as a straw man, now that neo-Darwinism has moved on. It is

whole new phyla!

These were

radically

novel designs!" I trust this was never true that Darwin tended to insist, shortsightedly, on the gradual nature of all Gould's point, because if it was, it was an embarrassing fallacy of extinctions, but it has long been recognized by neo-Darwinians that this was retrospective coronation; as we have already seen,

all

new phyla—indeed, due to his eagerness to distinguish his view from

304 BULLY FOR BRONTOSAURUS

Tinker to Evers to Chance

305

the varieties of Catastrophism that stood in the way of acceptance of the convincing story about why the winners won and the losers lost. Who theory of evolution by natural selection. We must remember that in Darwin's knows? One thing we all know: you can't make a scientific revolution out of day miracles and calamities such as the Biblical Flood were the chief rival to an almost untestable hunch. (See also Gould 1989a, pp. 238-39, and Daw-Darwinian thinking. Small wonder he tended to shun anything that seemed kins 1990 for further observations on this score.)

suspiciously swift and convenient.

So we are

still

stuck with a mystery about what Gould thinks is so special The fact (if it is one) that the Burgess fauna were decimated in a mass about the unique flourishing and demise of these amazing creatures. They extinction is in any case less important to Gould than another conclusion he inspire a suspicion in him, but why? Here's a clue, from a talk Gould gave at wants to draw about their fate: their decimation, he claims (1989a, p. 47n.), the Edinburgh International Festival of Science and Technology, "The Indi-was

random.

According to the orthodox view, "Survivors won for cause,"

vidual in Darwin's World" (1990, p. 12):

but, Gould opines (p. 48), "Perhaps the grim reaper of anatomical designs was only Lady Luck in disguise." Was it truly

just

a lottery that fixed

all

their In fact almost all the major anatomical designs of organisms appear in one fates? That would be an amazing—and definitely revolutionary—claim, es-great whoosh called the Cambrian Explosion about 600 million years ago.

pecially if Gould then extended it as a generalization, but he has no evidence You realize that a whoosh or an explosion in geological terms has a very for such a strong claim, and backs away from it (p. 50): long fuse. It can take a couple of million years, but a couple of million years in the line of billions is nothing.

And that is not what that world of

I am willing to grant that some groups may have enjoyed an edge (though

necessary, predictable advance ought to look like

[emphasis added].