Dead: A Ghost Story

Read Dead: A Ghost Story Online

Authors: Mina Khan

Tags: #Multicultural, #Ghost, #immigrant, #womans fiction, #asainamerican

DEAD: A Ghost

Story

Mina Khan

Smashwords

Edition

License

Agreement

This ebook is licensed for

your personal enjoyment only. This ebook may not be re-sold or

given away to other people. If you would like to share this book

with another person, please purchase an additional copy for each

recipient. If you’re reading this book and did not purchase it, or

it was not purchased for your use only, then please return to

Smashwords.com and purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting

the hard work of this author.

This is a work of fiction. Names,

characters, places, and incidents are either the product of the

author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance

to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events,

or places is entirely coincidental.

Thank you for reading!

Nasreen watches in shamed

silence as her husband and the Hispanic woman have sex.

He is on top, eyes

scrunched shut, thrusting, plunging in and out as if driven by hard

fury. Matin’s flabby arms shake under the strain. A series of short

grunts mark his efforts. Maria lies under him with her legs

sticking up in the air in a wide open V and red nails digging into

his pale, hairy back. She lets loose long guttural moans from time

to time and a few feverish “Ay, Papi!”-s, all the while watching

the flickering television over Matin’s shoulder. His belly slaps

into her body, over and over again. Slap, slap, slap.

Finally, their faces

freeze in ugly grimaces. They let out joint yowls and collapse in a

tangle of limbs in different shades of brown. The sour smell of

sweat and sex bloats the small room.

Hovering above them,

Nasreen sees Matin’s bald spot sticking out like an egg in his nest

of unruly black hair. Her gaze traces the age spots flecking

Maria’s arms and thighs and notices the faded pink flowers in the

twisted sheets that hadn’t been changed since she last slept in the

bed.

In disgust, Nasreen turns

away and finds herself swept up to the rafters. She still isn’t

used to being dead and without the weight of her body. She swirls

around, despondent and unsettled.

Watching the animal

rutting brings back bad memories of all the times her husband had

demanded his “rights.” Even now, she wants to scratch and kick at

him, scream her hatred. She’d tried. Instead of satisfying impact,

her fists simply went through Matin. Her mouth moved soundlessly

when she’d tried to hurl accusations at him. They don’t see her

now, standing there glaring at them. She doesn’t even cast a

shadow.

A shudder of regret passes

through Nasreen. Why did she exist as a mere shadow when she’d been

alive? Why did she swallow all those bitter words in the name of

family peace? Why didn’t she use her God-given legs to simply walk

away? Now she is of even less substance than the fragile and

forgotten cobweb hanging in the darkest corner of the house. The

thought makes Nasreen’s eyes burn with hot, stinging tears. Loud,

heavy sobs wrench out of her as she realizes that in death, as in

life, she’s nothing.

In bed, both Maria and

Matin tense up. Their eyes fly open, they lie very still, holding

their breaths.

“

What was that?” Maria

whispers. “Did you hear it?”

Matin, silent for a few

heartbeats, shakes his head. “It’s the wind. Just the

wind.”

“

It sounded like a woman

crying,” Maria says, as she snuggles deeper into his soft chest.

“Such a sad sound.”

Nasreen stops crying and

stares. Did they hear her or was it really the wind? She shouts,

“Matin, you selfish bastard!” Her words fall soundlessly into the

room.

Disappointed, she sinks

down, through the floorboards, into the living room with its orange

shag carpet. The hum of the window unit fills the silence. The

smell of old cooking— laced with chilies and turmeric and cumin—

hangs like an oily curtain in the air. Nasreen winds her way to the

kitchen, her hand brushing against the peeling blue wallpaper with

its orange and white flowers. A whisper soft Shhhh-shhh-shh

accompanies her progress. Hope ignites inside like a candle,

already melted into a short stub. She plucks at the paper. But her

ghost fingers can’t grasp, can’t hold on. If only she’d torn the

paper off the walls while she’d been alive and able. With a sigh, a

last touch, she leaves the wall behind.

She stands in front of the

kitchen sink looking out of the single window -- a familiar stance,

a familiar view. The sky is white hot. The earth, flat and dusty,

dotted with scrawny shrubs. The kiss between sky and earth is dry

and parched. The panorama stretches, unraveling, as far as Nasreen

can see, just like it had the day she’d arrived in Sand Lake,

Texas, seven years ago.

Matin had bought a

second-hand station wagon, piled Nasreen and all their belongings

into it and driven them all the way from New York.

“

It’s going to be a new

opportunity, a new beginning,” he’d said. “We’re going to be hotel

owners!”

She should’ve known

better, known that like all of Matin’s promises, this too would be

overblown and full of holes. Reality had been a motel, with peeling

gray paint and dead weeds dancing in the wind. A faded sign,

proclaiming “The Grande Motel,” squeaked to and fro above the front

office door. The sulfur smell of rotten eggs filled the air,

proclaimed it oil country. Bill’s Feed Store and the notary

public’s office flanking the motel had closed for the

day.

Desolation pressed down on

Nasreen, hot and oppressive. She’d stood in her blue cotton sari

and flip-flops —her concession to summer—in the cracked asphalt

parking lot, empty except for their station wagon, and

cried.

Until Matin shot a glob of

spit right at her feet. “Shut up and help me unload.”

Nasreen had stared at him

as if he was a part of the strangeness around her. She drew in

long, sob-laced gulps of breath. Her slippers, her sari,

everything, felt wrong.

Nasreen trembles gazing at

the land, so different from the land she’d known growing up. In

West Bengal, especially during the monsoon season, everything was

green. The trees, the grass, the vines --all came in so many

different shades of green. Greens that seemed to breathe, grow and

brighten with every beat of her heart. Once, she’d taken all that

life for granted. Now her eyes itch as the Texas heat sucks dry

every blade of grass, every clod of earth, every bit of

moisture.

Footsteps echo on the

stairs and Nasreen drifts over to watch Matin and Maria descend.

They are holding hands. She wonders how long their affair has been

going on. They look comfortable with each other, familiar, no

self-conscious fumbling and stumbling. Nasreen shakes her head as

she remembers the awkwardness of her first encounters with Matin,

with sex and physical intimacy, with being a wife.

The first time they met,

Nasreen had been nineteen and Matin thirty-six. On holiday from

America, he visited Nawabpur, his mother’s paternal village. His

mother’s grandfather, Alok Chowdhury, and his ancestors had owned

the entire village once upon a time. However, much of that

ancestral wealth had disappeared. Matin’s cousins turned to

business and trade to eke out a living. But the memory of the

family’s grandeur remained, shimmering like a fantastic mirage,

mesmerizing all.

Nasreen’s father was the

mathematics professor at the local college. His government job

provided him a small house and an even smaller salary, adequate for

the widower and his only daughter. Then one evening, Sayeed

Chowdhury -- a comfortably middleclass businessman and direct

descendant of Alok -- brought his American cousin for a visit. They

claimed to have come for intellectual conversation. Nasreen served

them tea.

Matin was immediately

taken by her. He’d told her later that her shyness had stirred his

loins. Her long hair, a silky black curtain down her back, fueled

his fantasies. He sent a proposal before the end of the

week.

Nasreen remembered Matin’s

heavy jowls, his pockmarked skin and the potbelly stretching his

shirt and said no. Her father sighed.

“

Ma, be reasonable,” he’d

said. “I’m growing older every day and I would never forgive myself

if I were to die without marrying you off. Your husband will take

care of you after I’m gone.”

The professor said Matin’s

proposal was the best that she, a poor teacher’s daughter, could

expect. In fact, Matin was better than what could be expected -- a

successful businessman from America and of Chowdhury blood. Her

father borrowed a book of maps from the college library and pointed

out New York to Nasreen. It seemed so far away, so unreal -- a

small blotch of color on a page that could be turned and

forgotten.

Matin visited almost

daily, carrying sweets and books. He told wonderful tales of

America with its shiny buildings stretching to the sky; clean,

air-conditioned shops that had more things than could be imagined,

like sweaters for dogs and socks with bells; and underground trains

that carried millions of people. He laughed and spoke of being a

lucky man. He’d won the American visa lottery, after

all.

Her friends were envious,

she was going abroad, to the land of plenty where no one went

hungry or wore threadbare saris. Every one of them had heard

stories of America from a lucky relative who’d made it to that

distant land. One of them noticed her sadness and remarked, “Eeesh!

I don’t know why you’re pretending such sadness? My sister’s

husband’s cousin’s son says anything is possible in America. You

should see his car, tomato red and shiny, with no roof. Brand new!

I saw a photograph he sent back.”

But when two fat tears

rolled down Nasreen’s face, the other girl had softened. “Don’t

worry so much,” she’d said. “With a new husband, and a new home

--you won’t have time to miss this old place.”

Matin and Nasreen married

within a month. Her father used most of his savings to buy three

sets of gold jewelry as her wedding present.

“

I wish I could do more,”

the professor told Nasreen. “But at least now the Chowdhuries will

know they are getting a girl from a respectable family.”

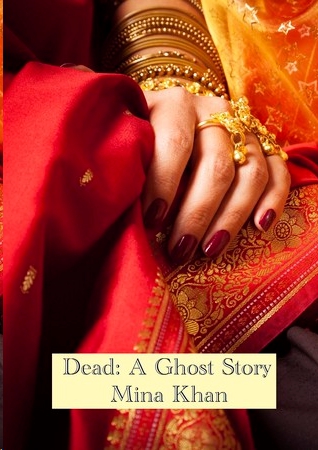

Nasreen floats in front of

the framed wedding picture, prominently displayed on the fireplace

mantle in the living room. Matin is wearing a long white groom’s

coat with gold embroidery and loose pants. A pink, silk turban sits

on his head and a thick flower garland hangs on his neck. She is

dressed in a red and gold

benarasi

sari, a matching flower garland and almost all her

gold jewelry, standing next to him.

Or rather, she’s almost

hidden by his bulk. His thick lips are split in a

self-congratulatory smile as he clutches her hand, while she stares

at the camera in wide-eyed panic.

“

I don’t like that

picture,” Maria says, startling Nasreen out of her

thoughts.

Matin laughs. It sounds

coarse and rude. “Why? Are you jealous?”

“

No,” she says, barely

suppressing a shiver. “But your wife seems to be staring at me,

watching me.”

Her words, feathered with

fear, make Nasreen smile. A small flare of petty pleasure launches

through her. Part of her feels guilty. But then some days that was

the only kind of pleasure to be had.

“

Don’t be silly,” Matin

says, stomping away. “Make us some lunch. I’ll be in the front

office for a bit.”

He leaves Maria sitting on

the lumpy brown couch still looking at the picture. After a while,

she shrugs her soft, round shoulders and pushes to her feet. She

walks from room to room whistling a tune.

Nasreen follows, close

enough that if she were breathing Maria would have felt the puffs

of air on her neck. She watches the woman rifle through closets and

drawers, peek under the mattress and bed, and even search inside

Matin’s shoes. Nerves prickle through her.

Maria pulls out some cash

from an old dress shoe in the back of the closet, counts it and

carefully puts it back. Nasreen’s right hand flies to her mouth.

Why had she never thought of doing this? God, she’d been nothing

more than a placid cow until led to slaughter.