Dead Scared

When a Cambridge student dramatically attempts to take her own life,

DI Mark Joesbury

realizes that the university has developed an unhealthy record of young people committing suicide in extraordinary ways.

Despite huge personal misgivings, Joesbury sends young policewoman

DC Lacey Flint

to Cambridge with a brief to work undercover, posing as a vulnerable, depression-prone student.

Psychiatrist

Evi Oliver

is the only person in Cambridge who knows who Lacey really is – or so they both hope. But as the two women dig deeper into the darker side of university life, they discover a terrifying trend . . .

And when Lacey starts experiencing the same disturbing nightmares reported by the dead girls, she knows that

she is next

.

In memory of Peter Inglis Smith:

kind neighbour, great writer, good friend.

What are fears but voices airy?

Whispering harm where harm is not

,

And deluding the unwary

Till the fatal bolt is shot!

William Wordsworth

Tuesday 22 January (a few minutes before midnight)

WHEN A LARGE

object falls from a great height, the speed at which it travels accelerates until the upward force of air resistance becomes equal to the downward propulsion of gravity. At that point, whatever is falling reaches what is known as terminal velocity, a constant speed that will be maintained until it encounters a more powerful force, most commonly the ground.

Terminal velocity of the average human body is thought to be around 120 miles per hour. Typically this speed is reached fifteen or sixteen seconds into the fall, after a distance of between five hundred and six hundred metres.

A commonly held misconception is that people falling from considerable heights die before impact. Only rarely is this true. Whilst the shock of the experience could cause a fatal heart attack, most falls simply don’t last long enough for this to happen. Also, in theory, a body could freeze in sub-zero temperatures, or become unconscious due to oxygen deprivation, but both these scenarios rely upon the faller’s leaping from a plane at significant altitude and, other than the more intrepid skydivers, people rarely do that.

Most people who fall or jump from great heights die upon impact when their bones shatter and cause extensive damage to the

surrounding

tissue. Death is instantaneous. Usually.

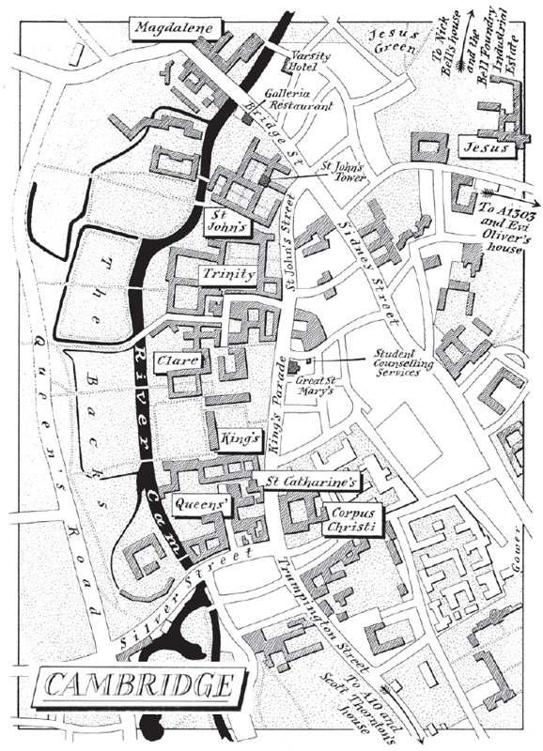

The woman on the edge of one of the tallest towers in Cambridge probably doesn’t have to worry too much about when she might achieve terminal velocity. The tower is not quite two hundred feet tall and her body will continue to accelerate as she falls its full length. She should, on the other hand, be thinking very seriously about impact. Because when that occurs, the flint cobbles around the base of the tower will shatter her young bones like fine crystal. Right now, though, she doesn’t seem concerned about anything. She stands like a sightseer, taking in the view.

Cambridge, just before midnight, is a city of black shadows and gold light. The almost-full moon shines down like a spotlight on the wedding-cake elegance of the surrounding buildings, on the pillars pointing like stone fingers to the cloudless sky, and on the few people still out and about, who slip like phantoms in and out of pools of light.

She sways on the spot and, as if something has caught her attention, her head tilts down.

At the base of the tower the air is still. A torn page of yesterday’s

Daily Mail

lies undisturbed on the pavement. Up at the top, there is wind. Enough to blow the woman’s hair around her head like a flag. The woman is young, maybe a year or two either side of thirty, and would be beautiful if her face weren’t empty of all expression. If her eyes had any light behind them. This is the face of someone who believes she is already dead.

The man racing across the First Court of St John’s College, on the other hand, is very much alive, because in the human animal nothing affirms life quite like terror. Detective Inspector Mark Joesbury, of the branch of the Metropolitan Police that sends its officers into the most dangerous situations, has never been quite this scared in his life before.

Up on the tower, it’s cold. The January chill comes drifting over the Fens and wraps itself across the city like a paedophile’s hand round that of a small, unresisting child. The woman isn’t dressed for winter but seems to be unaware of the cold. She blinks and suddenly those dead eyes have tears in them.

DI Joesbury has reached the door to the chapel tower and finds

it

unlocked. It slams back against the stone wall and his left shoulder, which will always be the weaker of the two, registers the shock of pain. At the first corner, Joesbury spots a shoe, a narrow, low-heeled blue leather shoe, with a pointed toe and a high polish. He almost stops to pick it up and then realizes he can’t bear to. Once before he held a woman’s shoe in his hand and thought he’d lost her. He carries on, up the steps, counting them as he goes. Not because he has the faintest idea how many there are, but because he needs to be marking progress in his head. When he reaches the second flight, he hears footsteps behind him. Someone is following him up.