Death Ex Machina (2 page)

Authors: Gary Corby

SCENE 1

REHEARSAL FOR DEATH

I

N MY TIME as an investigator I had received many difficult assignments, problems that were usually dangerous, often deadly, and sometimes downright impossible.

But no one before had ever asked me to arrest a ghost.

“You can’t be serious, Pericles,” I said.

“Of course I’m not,” he replied. He sounded exasperated. “But unfortunately for both of us, the actors are completely serious.”

“What actors?” I asked.

“The ghost is in the Theater of Dionysos,” Pericles said. “The actors refuse to enter the theater until the ghost is gone.”

“Oh,” I said, and then, after I’d thought about it, “Oh dear.”

The timing couldn’t be worse, because the Great Dionysia was about to begin. The Dionysia was the largest and most important arts festival in the world. Thousands of people were flocking into Athens. They came from every corner of civilization: from the city states of Greece, from Egypt and Crete and Phoenicea and Sicily, from Ionia and Phrygia. All these people came to hear the choral performances and to see the plays: the comedies and the tragedies.

Most of all they came for the tragedies. Every city has fine singers. Every city has comics who can make you laugh. But only Athens, the greatest city in all the world, has tragedy.

“The producers have ordered the actors back to work,” Pericles said. “The playwrights have begged them, even I have spoken to them, but the actors say they fear for their lives.”

He wiped the sweat from his brow as he spoke. Pericles had hailed me in the middle of the agora, which at this time of the morning was always crowded. He had called me by my name, so loudly that every man, woman, and child in the marketplace had turned to look. Then Pericles had lifted the skirt of his ankle-length chiton and in full view of the people had run like a woman, leaping over jars of oil for sale and dodging around laden shoppers, all to speak with me. That alone told me how serious the situation was. Pericles prided himself on his statesman-like demeanor. It was part of the public image he courted as the most powerful man in Athens.

It was easy to see why Pericles was worried. If the actors refused to rehearse, they would put on poor performances. We would look like idiots before the rest of the civilized world. Or worse, the actors wouldn’t be able to perform at all. The festival was in honor of the god Dionysos, who in addition to wine and parties was also the god of the harvest. If we failed to honor the God as was his due, then there was no telling what might happen to the crops. The people might starve if Dionysos sent us a poor year.

There was no doubt about it. The actors had to be induced to return to work.

Pericles said, “What I want you to do, Nicolaos, is make a show of investigating this ghost. Do whatever it is you do when you investigate a crime. Then do something—anything—to make the actors think you’ve captured the ghost.”

“How do you get a ghost out of a theater?” I asked.

“How in Hades should I know?” Pericles said. “That’s your job.”

I couldn’t recall placing a “Ghosts Expelled” sign outside my door.

“Surely there must be someone who can do this better than me,” I said.

“You’re the only agent in Athens, Nicolaos,” Pericles said in

persuasive tones. “The only one who’ll investigate and then tell the people that the ghost is gone.”

Which was true. Though there were plenty of thugs for hire, and mercenaries looking for work, I was the only man in Athens who took commissions to solve serious problems. I pointed out this commission aspect to Pericles.

“You may consider this a commission,” Pericles said, through gritted teeth. He hated spending money.

The promise of pay put another complexion on it. When Pericles had waylaid me I had been on my way to see to my wife’s property. My wife, Diotima, owned a house on the other side of the city, one in a sad state of disrepair. Repairs cost money. Money I didn’t have.

I still didn’t think I was the man for the job. Yet I reasoned it must be possible to remove a ghost, assuming such things even existed. Otherwise our public buildings would be full of them, considering how many centuries the city had stood.

Expelling a ghost might prove difficult, but it certainly wasn’t dangerous, deadly, or downright impossible. I made an easy decision.

“Then I shall rid the theater of this ghost,” I promised Pericles.

SCENE 2

THE PSYCHE OF THE GREAT DIONYSIA

T

HE CASE WAS urgent. I abandoned my plan to see to repairs and turned around. I had no idea about ghosts, but I knew someone who would. I went home to ask my wife.

I found Diotima in our courtyard. She reclined on a couch, with a bowl of olives and a glass of watered wine by her side. My little brother, Socrates, stood before her, reciting his lessons. Socrates had been expelled from school the year before, for the crime of asking too many questions. Ever since then, Diotima had been his teacher. The arrangement had worked surprisingly well.

I interrupted the lesson to deliver my news.

“There’s no such thing as ghosts,” Diotima said the moment I finished speaking. She paused, before she added thoughtfully, “Of course, there might be a

psyche

haunting the theater.”

“Is there a difference, Diotima, between psyches and ghosts?” Socrates asked. He’d listened in, of course. I’d long ago given up any hope of keeping my fifteen-year-old brother out of my affairs.

“There’s a big difference, Socrates,” Diotima said. “Everybody has a

psyche.

It’s your spirit, the part of you that descends to Hades when you die. Ghosts, on the other hand, are evil spirits that have never been people. The religion of the Persians has evil spirits that they call

daevas.

I think the Egyptians have evil spirits too. But we Hellenes don’t credit such things.”

“Then the actors might have seen a psyche?” Socrates said.

Diotima frowned. “I hope not. If a body hasn’t been given

a proper burial then its psyche will linger on earth. It should never happen, but sometimes it does.” She turned to me. “Nico, are there any dead bodies lying about the theater?”

“I like to think someone would have mentioned it if there were,” I said. “If there’s a body, we’ll have to deal with it, but there’s another possibility.”

“What’s that?” Diotima asked.

“That the actors are imagining things.” I helped Diotima off the couch. “We’ll have to go see for ourselves.”

SCENE 3

THE GHOST OF THESPIS

S

OCRATES TAGGED ALONG. There are few things harder to shake than a little brother.

Our house lies outside the city walls, to the southeast. The three of us entered the inner city through the Itonian Gate.

Two guards stood on duty, both of them bored, but too scared to slack off for fear their officer would check on them. They were

ephebes

, trainee recruits who were serving out their mandatory two years in the army, as must every young man from the moment he turns eighteen until he’s twenty. I knew how bored they were because three years ago, I’d been one of them.

These two were local lads from our own deme. Their families lived only a few streets from our own. They knew us and waved us through with a pleasant word and an appreciative glance at Diotima.

Diotima wore a new chiton of linen that she’d dyed in bright party colors. When she’d appeared in it that morning, I’d pointed out that the Great Dionysia hadn’t begun yet. Diotima had replied that it was close enough.

She wasn’t the only one to have started early. Many of the travelers who passed through the gate were already in their best, brightest clothes. Complete strangers talked to one another, smiled and laughed at each others’ jokes. Even the air we breathed was in a party mood. The one thing you are guaranteed to find at any gate in Athens is donkey droppings, yet on this day the aroma was fresh and pleasant. Diotima said it

was because Gaia, who ruled the Earth, wished Dionysos well. I suggested it might have more to do with the frequent showers we’d been having. The rain kept down the dust. Diotima replied that was Gaia’s way of arranging things.

We walked north up Tripod Road. Both sides were lined with three-legged braziers. They were the trophies given to previous winners at the Great Dionysia, each erected along this road, with a plaque, for the passersby to admire and for the victors to gloat. One of those trophies belonged to Pericles. He had been the

choregos

—the producer—of a winning play fourteen years ago. The truth is that Pericles had won because he’d hired Aeschylus to write the script. When you’re Pericles, you can afford the very best. He was inordinately proud of that achievement. Every day since, Pericles had sent a slave to polish his trophy.

We turned left just before the Acropolis, onto a street that was well kept but that had seen recent heavy use. It was Theater Road, and right before us was the Theater of Dionysos. The Acropolis towered above, directly behind the theater.

A wooden wall painted in blues and reds blocked the view of the backstage. Men clustered at this wall. As we approached, we could hear them arguing with tired voices. The way they stood with shoulders bowed, I guessed they’d been at it for some time.

“… and I tell you again, Sophocles, we’re not going in there until the ghost is removed.”

“I remind you once more, gentlemen, there are no such things as ghosts.”

The man who didn’t believe in ghosts was of middle age, with a long face that was well bearded. I thought he must buy his clothes from the same place as Pericles. Both of them were top-notch in respectable fashion. This man must be the one of the playwrights, or a choregos.

The argument broke off when Diotima, Socrates, and I stopped before them.

“Who are you?” one of the men asked. He was dressed in an

exomis

, typical clothing for an artisan. I guessed he must be a stagehand. I preferred an exomis myself because it left my arms and legs free to move.

“Nicolaos, son of Sophroniscus,” I said. “Pericles asked me to look into this ghost.”

The well-dressed man looked at me oddly.

“You’re going to get rid of the ghost?” someone else asked. I would need to learn all their names before this was done. For now I thought of him as the one with the strong muscled arms.

“Yes,” I said confidently.

“Who are they?” He pointed rudely at Diotima and Socrates.

“My brother and my assistant,” I said. “This lady is an expert on ghosts.”

Diotima looked startled. She said, “But Nico, there’s no such thing as—ouch!”

I’d stamped on her foot.

“There’s no such thing as a ghost Diotima can’t find,” I finished smoothly.

They looked doubtful.

“Well, I may as well get started,” I said cheerfully. “Let’s have a look at the haunted theater, shall we?”

“I’m not going in there, it’s dangerous!” said the well-muscled man.

I’d wondered if the whole story might be an excuse to avoid work, but the man was genuinely scared. So, by the look of them, were the others. I said, “If you won’t, who will?”

“I am Sophocles, son of Sophilos,” the well-dressed man said.

“Are you a choregos, sir?” I asked.

Sophocles grimaced. “If I was, I would this moment be facing financial ruin. No, young man, I am the playwright, and if this problem is not solved then my only fear is utter professional disgrace before my fellow citizens.”

He glared at the men about us.

“If these foolish men are too scared to enter the theater, I am not. Let us go.”

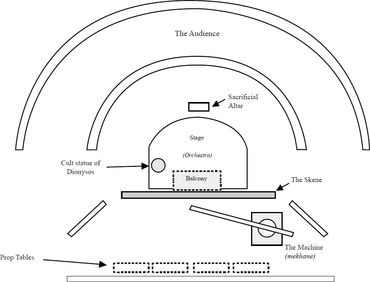

The backstage was open to the sky. Another wall hid the backstage area from the audience’s view. The effect was a room with no roof and wide entrances to each side. The walls that were so gaudy on the outside were rough, unpainted and drab within. It seemed that theatrical illusion stopped at the surface.

One large item dominated the space.

“What is

that

?” I said, pointing.

“That’s the machine,” Sophocles said. “We use it to lift actors into the air when they’re playing gods.”

“Oh, of course.”

I’d seen actors float off the ground during plays. They hung from a rope at the end of a wooden arm. I’d never given a thought to what must be happening behind the scenes. The machine looked much like the dockside cranes at the wharves at Piraeus. I said as much to Sophocles.

“Very similar,” Sophocles agreed. “Ours is of more delicate construction. We need a longer arm to reach over the

skene

—that’s

the wall you see there that separates us from the stage—and ours has a thinner arm so it’s less noticeable. Our machine only needs to lift a man.”

“Sir, may I ask, how does the machine work?” Socrates asked. He stared at it in fascination.

Sophocles looked at the boy in surprise, then said, “Well, lad, three men hold the end with the short arm. They pull down and the long arm goes up. They push the short arm sideways and the long arm goes over the skene. It’s very simple.”

“Yes, sir, I see that,” Socrates said. “But three men couldn’t normally lift one man so high, could they?”