Death Sentence (56 page)

“That evening I felt I had reached the lowest point in my life,” he said years later.

He knew that he was going to have to quit drinking and get his life back in order, and he vowed to himself that he would do it.

A month later, he had a job in a department store warehouse. And he had cut back on his drinking, although he hadn’t stopped. He refused to drink in his room but still allowed himself to go out and drink several nights each week.

By the end of his first year in Raleigh, Ronnie had saved $900, and acting on impulse, he quit his job and went to Nashville with a guitar player he met. Two weeks later, the guitar player had disappeared along with much of Ronnie’s savings and most of his possessions. Shamed and feeling foolish, Ronnie returned to Raleigh. He moved back into the same rooming house and went to work part-time for its owner.

In the summer of 1991, Ronnie got a job with a tire company and found himself liking it. Two years later, he had weaned himself from alcohol and had moved from the rooming house into an apartment with a friend. His life was beginning to get back on track. A year later, the year Michael turned eighteen, and the unpaid support payments stopped accumulating, Ronnie called the clerk of court in Scotland County and tried to work out an arrangement to start paying some of the money he owed.

But it was another year before he could bring himself to try to fill the greatest void in his life—the absence of the people he loved. He had completely lost touch with Pam, had not seen her in nine years, had had no contact for more than six. But in the fall of 1995, he found out where she was living and called.

He did not recognize the voice that answered.

“I’d like to speak to Pam Jarrett, please,” he said.

“This is she.”

“Well, this is your long-lost brother.”

“No, it isn’t,” she said. “Who is this?”

“Ask me a few questions,” Ronnie told her with a chuckle.

She caught his laugh and began to cry.

“I thought you were dead,” she said. “Where have you been?”

She could not believe that he was in Raleigh.

They talked for a long time, catching up, and at one point Pam asked, “Have you talked to Michael?”

“No, I haven’t seen him in eight years,” Ronnie said.

“There’ll come a time when you’ll need to do that,” she told him.

“I know,” he said, but he wasn’t ready yet for that.

“If I send you a plane ticket, will you come and spend Thanksgiving with me?” Pam asked.

Ronnie agreed, and later neither of them could remember a happier or more satisfying Thanksgiving since childhood.

During their visit, Pam again encouraged Ronnie to make contact with Michael, and they talked at length about how Michael might react, and how Ronnie might handle the situation. Ronnie’s great fear and reluctance was that Michael would reject him, would never want anything to do with him.

A week after his return to Raleigh, Ronnie got up nerve enough to call Joanna’s parents. He talked with her mother and told her his whereabouts. A week later, his telephone rang, and anxiety shot through him when he heard Joanna’s voice.

“Michael wants to talk to you,” she said. “Are you prepared for that?”

“I think so,” Ronnie said, but he was so nervous that he wasn’t certain that he could handle it.

Michael had been ten when he last had spoken with him. Now a deep male voice was on the line saying, “How you doin’, stranger?”

“Is this Michael?”

“Yeah, Daddy, it’s Michael.”

The conversation was awkward and superficial. They talked of sports, music, school, but nothing meaningful.

“I’d sure like to see you,” Ronnie said.

“I’d like to see you, too.”

Not until a couple of months later, however, did they finally arrange a meeting. Ronnie drove to Laurinburg and pulled into the parking lot at Wendy’s where Michael had said he would meet him. He saw the old yellow Chevy that Michael had described, a young man behind the wheel, a baseball cap pulled low on his forehead. Ronnie parked nearby, got out and started toward the car. The young man opened the door and unfolded from it. He was six-three and big enough to be a football lineman.

Ronnie was astonished. Suddenly, he found himself running toward him. “You’re a man,” he said, drawing up short and offering his hand.

Michael grinned and took his hand.

“No, you’re my son,” Ronnie said, and grabbed him in an awkward bear hug.

“How are you doing?” he asked, releasing him.

“I’m good.”

“It’s so good to see you. I love you.”

“I love you, too.”

Michael had agreed to spend the weekend with him, and on the way back to Raleigh Ronnie tried to explain himself.

“I’ve been through a lot of problems. I’ve been mixed up. I’ve made a lot of mistakes. There’s no logical reason I can give you for why I did what I did. I’ve behaved very irresponsibly to you and your mother. None of it’s your fault. It’s not that I haven’t wanted to see you, it was just that I was so embarrassed and ashamed by my behavior. I don’t expect you to understand it all. If you want to be mad at me and hate me for it, that’s a natural feeling and I won’t hold it against you.”

“I don’t,” Michael said.

“I’m going to try to do my best from now on,” Ronnie assured him.

Renewing his relationships with his sister and his son did not prove to be an end to Ronnie’s problems, however.

When a promised managerial position was given to a younger man, Ronnie quit the tire company where he had worked happily for more than four years, and afterward he was not able to find a regular job. A series of kidney stones left him addicted to pain pills, and after he had beaten that, he found himself in deep depression. For a while he sought professional counseling, but could not afford to continue. At one point in 1997, he found himself again broke, without work, and with no place to stay. For a brief period, he lived in his car. But he did not turn back to alcohol or drugs, and a friend took him in and gave him work.

As a new year arrived, he finally had begun to confront what lay at the root of his problems: his relationship with his mother, the long-suppressed guilt he felt about her arrest, conviction and execution, as well as his guilt about the murders of his father, his grandmother and his mother’s other victims.

“I’m going to recover,” he said with certainty. “My intentions are to recover from every bad thing that has happened to me, and I am determined to do that. I made a lot of bad decisions and a lot of bad mistakes, but I am going to recover from all of them.

“I’m going to do everything I can to keep my relationship with my son. I think he probably has a lot of hurt that he hasn’t let out yet. I hope that I can help him let it out and that he’ll love me again the way he did when he was little.

“I’ve just got a feeling there’s something for me to accomplish yet. I’ve got a feeling that someday somebody is going to need me and maybe I’ll be strong enough to help them.”

Afterword

On the day after Velma’s death, an editorial appeared in the

New York Times

headlined “What Velma Wore.” It took note that she died in pink pajamas and ate Cheez Doodles for her final meal.

A day was coming, the newspaper observed, when we wouldn’t know such details about the condemned, because executions would be so commonplace that they would attract little attention.

The

Times

was right. By mid-spring of 1998, 452 executions had taken place in the United States since the reinstatement of the death penalty in 1976—seventy-four in 1997 alone—and almost all passed largely unnoticed.

Only one of the condemned attracted as much attention as Velma. Her name was Karla Faye Tucker, and on February 3, 1998, she became only the second woman to be executed in the United States since 1962 when she was put to death by lethal injection in Texas.

As with Velma, death-penalty supporters were quick to point out that the only reason Tucker’s pending execution had raised such a clamor was because she was a woman—and a particularly attractive, personable, and articulate one who performed well on TV. The point was well taken.

Clearly, the people of the United States had little taste for executing women. They didn’t even like trying them for their lives. And statistics proved it.

While women accounted for thirteen percent of murder arrests in the country, men received more than ninety-eight percent of death sentences. And even when women received death sentences, they were far more likely to have them overturned. At the beginning of 1998, women made up only slightly more than one percent of the occupants of the nation’s death rows.

Although the United States Supreme Court cited racial disparity as the reason for declaring the death penalty unconstitutional in 1972, it had never taken on the issue of gender disparity. And while, as some death rows have again grown lopsided by race, some state legislatures have enacted “racial justice” acts allowing defendants in capital cases to cite statistical evidence of racial discrimination to avoid the death penalty, no state has enacted a “gender justice” act.

Neither Velma nor Karla Faye Tucker, a double murderer who, like Velma, had undergone a religious conversion in prison, claimed that they should be allowed to live simply because they were women, however.

Although their cases drew attention to gender disparity in the death penalty, the issue they both raised for society was much different: redemption. Because they had turned their lives around and were contributing to society in prison, they held that they no longer deserved to die at the hands of the state. And both found many strong and prominent supporters for that position.

In a culture that believes in second chances, with penal systems that cite rehabilitation as their goals, they asked, shouldn’t redemption matter in relation to the death penalty?

The answer from the courts and from the governors of North Carolina and Texas was a resounding no. Yet after Tucker’s execution, polls showed a drop in support for the death penalty in Texas, which has executed more people than any other state in recent times.

Still, opponents of the death penalty held little, if any, hope that Tucker’s death would have a lasting effect. And evidence was quick in coming that the execution of a woman would never again attract the worldwide attention that Velma’s and Tucker’s cases had drawn.

On March 30, 1998, a fifty-four-year-old grandmother, Judy Buenoano, died in Florida’s electric chair without much press coverage or protest outside the state.

And while the prediction made by the

New York Times

after Velma’s death had already proved true, the courts and many of the nation’s governors have made it apparent that executions are going to become far more commonplace in coming years. Even if nobody else was ever sentenced to death in the United States, one person would have to be executed every day for more than ten years just to kill all the people on death row at the beginning of 1998.

Gallery

Velma Barfield thought she had escaped the misery of her childhood when she married Thomas Burke. She was newly married when she posed for this photo. (

Courtesy of Tyrone Bullard

)

Years later, Ronnie and Pam would long for the days when their parents were still happy, as they were on this trip to the North Carolina mountains when Ronnie was four, Pam three. (

Courtesy of Ronnie Burke

)

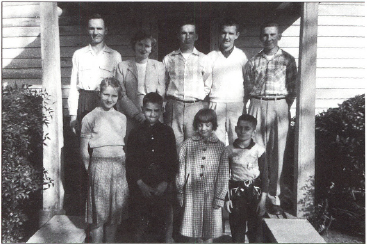

Velma Barfield was already the mother of two when she posed for this family snapshot with all her brothers and sisters. Back row (left to right): Olive, Velma, John, Jesse, and Jimmy. Front row: Arlene, Tyrone, Faye, and Ray. (

Courtesy of Tyrone Bullard

)