Authors: Michael Scott

Delphi (41 page)

The end of the war of independence, and the linking of Greece and Germany through the crowning of Otto, son of Ludwig of Bavaria, as king of the Hellenes in 1833, marked the beginning of a new phase both for Greek archaeology and for German scholarship in Greece. In 1829, Greek authorities had permitted a small excavation at Castri, which revealed the extraordinary sarcophagus of Meleager (now on display in front of the museum at Delphiâsee

fig. 11.3

). In 1831 the German Friedrich Thiersch made the first complete description of the site of Castri and its visible Delphic remains. In 1834 Ludwig Ross (a German scholar who was professor at the University of Athens) brought King Otto and his wife, Queen Amelie, to Delphi. The king even made the ascent up to the Corycian cave (see

figs. 0.2

,

1.2

). In return the local inhabitants petitioned the king for the construction of a small museum at Castri to safeguard finds that were turning up with increasing frequency. How to manage and protect the legacy of ancient Greece was an increasing concern. The first archaeological

site, the acropolis in Athens, had been officially designated in 1834. The Greek Archaeological Society was formed in 1837, and the first law concerning the selling and transportation of antiquities was passed in 1836. In 1838 Delphi was included in a list of sites where it was illegal to give as a dowry any piece of land on which there were antiquities.

31

Yet at Delphi, visitors' responses to the site were simultaneously turning in three different directions. First, the by now traditional lyric wonder and nostalgic disappointment. The Greek historian Andréas Moustoxydis, visiting the site in 1834, recommended that you travel by night to experience Delphi's mystery and then see at dawn its misery, as the site appears “in front of you, behind you, on top of you, all around you.” In September 1836 Prince Hermann von Pückler Muskau commented that “full of reverence, I hesitated to enter this sanctuary, even though all that I saw on the site of the temple was a lamentable village of wretched ruined houses.”

32

The second response was to attempt excavation where possible in among the village buildings. In 1840 Carl Müller undertook a small excavation of part of the Apollo temple substructure and polygonal wall (a part of which had first been exposed by Stuart and Revett less than a hundred years before). Müller's aim was to once again gaze on the temple sculptures, which scholars knew from the literary descriptions of Pausanias and Euripides. What the excavation produced, however, was not the hoped-for sculpture, but more and more inscriptions. Müller contented himself with recording as many of them as possible. But conditions at Delphi were harsh, particularly the summer heat. On 26 July 1840, Müller wrote to his wife:

I gambled on my ability to endure the heat and began to copy the inscriptions on an upturned stone, hanging upside down with the sun beating on my face. I paid dearly for this, however. I felt a burning in my skull, together with pain and irritation. I have reached the point where I am able to do no more at Delphi since every new attempt on my part re-awakens the pain, and I cannot even escape this incessant heat.

Just four days later, Müller died of sunstroke at the site.

33

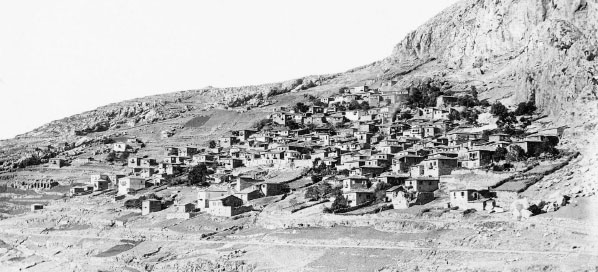

Figure 12.3

. An early photo of the town of Castri above Delphi before excavations began (© EFA [La redécouverte de Delphes fig. 48])

The third response, however, was to have the most important ramifications for the local villagers and, ultimately, for Delphi as well. From 1838 there was an attempt to begin the systematic release of ruins from under the village as part of a larger policy for rebuilding following the war of independence (

fig. 12.3

). The plan was for a gradual transfer of houses to a new site through a stick and carrot approach. The carrot was the offer to pay the locals to undertake the move. The stick was to forbid any more repairs to their current houses. The first stage in this process was to value all the properties and agree on a price with the local community. The locals responded, now all too well aware of the gold mine they seemed to be sitting on, by trebling the value of their homes. As a result, the plan ground to a halt, leaving the local villagers in the curious, and rather unhelpful position of not being able to repair their homes, yet with no agreement over what they might be paid to move, when they would move, or even where they would move. In 1841 three separate requests were made to the authorities to either get on with the plan and excavate or let them repair their homes (see

fig. 12.4

). Some locals took the matter into their own hands. The flamboyant Captain Dimos Frangos, capitalizing on the fact that all excavations so far had not been left open but had been refilled, took over the land that Müller had excavated (and died studying) in 1840 and built atop it the ancillary rooms of his house.

34

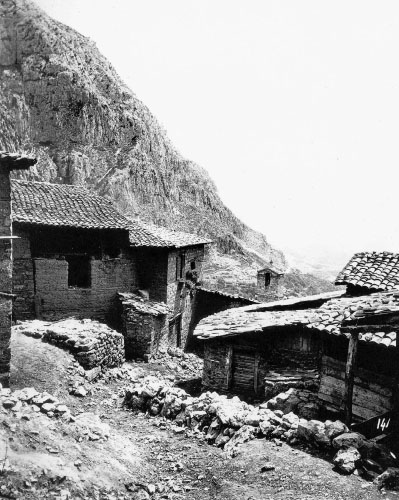

Figure 12.4

. An early photo of conditions in the town of Castri above Delphi before the excavations began (© EFA [La redécouverte de Delphes fig. 52])

In part thanks to the lack of success of the grand plan to completely uncover the site, the predominant activity at Delphi during the 1840s and 1850s was ongoing wonder coupled with nostalgic disappointment, fueled by small excavations where possible conducted both by the Greek archaeological service and by predominantly French and German scholars. In 1843 the German scholar Ernst Curtius published his

Anecdota Delphica

, and in 1858 the local villagers were proud enough of the heritage of their village, not to mention increasingly savvy about its implications for their own future wealth, to change the name on the door lintel of their village school from Castri back to Delphi.

35

Twelve hundred years since its abandonment in the early seventh century

AD

, Delphi was officially back on the map.

Yet in reality, Delphi was left out of the huge leaps forward in Greek archaeology during these decades. From the 1850s to the 1870s, significant discussions about the material culture of the ancient world were taking place in universities across Europe and transforming interest in ancient Greece from romanticism to erudition; and the poster-site for this transition was not Delphi, but Olympia. As Curtius, who had focused on Olympia since his early work on Delphi in 1843, demanded in his Berlin lecture on 10 January 1852, “When will the womb be opened again, to bring the works of the ancients to the light of day? What lies there in the dark depths is life of our life.”

36

Olympia, given its famous games, had the promise to deliver examples of the ideal of Greek physical beauty and architectural excellence the modern world clamored for, and scholars of ancient Greece thought key to understanding its culture. In 1874 the German Archaeological Institute was opened, and on 25 April 1875, the first legally explicit agreement between Greece and a foreign country for the excavation of an entire ancient siteâOlympiaâwas signed.

What was going on at Delphi during these years? Throughout the 1850s, the Greek authorities sought to keep records of objects found and the state of the site, noting with increasing concern that what was left would further disintegrate and perish if not more carefully looked after. So exasperated was Kyriakos Pittakos, the head of the Greek

Archaeological Society, that he even proposed in committee that a rich Greek be found to buy the entire site for purposes of excavation; and so worried was the Society about the survival of what was left at Delphi that it took official note of his proposition. Meanwhile, small excavations continued in 1861 and 1862, particularly by French scholars who, following the establishment of the French School in Athens on 11 September 1846, had a permanent base in the country. At the same time, the Committee of Antiquaries, founded in 1862 in Greece, declared its aim to raise money for excavating Delphi, money it hoped to earn through running a regular Greek lottery game. In 1867 a commission for excavating Delphi was formed, with one member of the committee, P. Kalligas, lawyer for the National Bank of Greece, pronouncing a harrowing assessment of the pitiful conditions found in the village of Castri/Delphi, which had, according to him, the highest infant mortality rate in Greece (see

figs. 12.3

,

12.4

). The fountain of Castri, it was pointed out, which had been cleaned out earlier in the nineteenth century, was, by the mid-1860s, once again filthy. But their efforts to prepare the ground for an excavation of Delphi to match that of Olympia also met with increasingly stiff resistance from local inhabitants who continued to demand a high price for their homes. The Committee of Antiquaries, with its grand aims, was dissolved in 1869.

37

The lack of progress in the 1860s is not surprising. Greece's focus was elsewhere, following the exile of King Otto, and the arrival of his replacement, King George I, in 1862, and the Cretan revolution in 1869. But on 20 July 1870, a wake-up call was delivered in the form of an earthquake. The village of Castri/Delphi was bombarded with rocks falling from the high cliffs of the Parnassian mountains, and thirty locals were killed. Here, amid the disaster, was an opportunity: the locals were understandably keener to move, the need to protect the ancient site clearer than ever. A new commission, this time diplomatically called “the Commission for the establishment of the inhabitants of Delphi,” was formed, with the aim of identifying a new site for the villagers to live in. The search was on to raise the money to effect the change. In 1871 the Greek Archaeological Society took the Russian ambassador to

Delphi to discuss the possibilities of excavation; and, though there was no money forthcoming from that quarter, in 1872, the Greek Archaeological Society was able to offer a loan to the Greek government in the amount of 90,000 drachmas for expropriation of the village. But negotiations were stifled by arguments first over the interest rate the Society could charge, and second by the locals' refusal to give up rights not only to their houses but also to their fields, and their demand that recompense be paid in a single sum and not in dribs and drabs.

38

Once more, the plans to excavate Delphi were on the back burner, but it was not long before wider events forced further action. The decade of the 1870s was a momentous one for excavation in Greece. In 1873 Schliemann found “Priam's treasure” at Troy (he visited Delphi in 1870). In 1875, work started at Olympia. In 1876 the French began to dig at Delos, just as Schliemann did at Mycenae, where he soon uncovered the shaft graves. Given such a spectacular rostra of discovery, the pressure was on for a place as important as Delphi to be excavated. The Greek Archaeological Society, which had been raising funds via the only legal lottery in Greece since 1876, began in 1877 to negotiate with individual locals to buy their property, thinking if they convinced a few key individuals, everyone else would follow suit. Captain Dimos Frangos was their target, and in 1878, he eventually agreed to sell his less-than-luxury house and property for the staggering sum of nine thousand drachmas.

39

But even if they managed to convince all the locals to sell up (and had enough cash to pay them), who would undertake such a massive and difficult excavation?

On 28 December 1878, Paul Foucart became director of the French School in Athens. He was one of the first of what have become known simply as “Delphiens”: scholars dedicated to Delphi. Foucart had uncovered parts of the polygonal wall in 1860 and was convinced the French should secure the right to excavate the site. He was not alone: since the Germans had signed an agreement to excavate Olympia in the mid-1870s, there had been tacit promises that the French could have the same deal elsewhere. In the corridors of the Congress of Berlin in June and July 1878, while the main business at hand was stabilizing the Balkans in the wake of diminishing Ottoman power, the French prime minister made

the first official request to the Greek delegation to excavate Delphi, and in 1880 the Greek Archaeological Society made a small area of land they had bought at Delphi available to the French for excavation. The results were promising, with parts of the Athenian stoa coming to light (see

plate 2

). Even more promising was the state of international affairs, particularly Greece's desire for further territorial gains at the expense of the Ottoman Empire, which inclined Greece toward doing what it could to secure French goodwill in return for support in the international negotiations. In 1881 a flurry of diplomatic activity between the Greek prime minister Alexandros Koumoundouros; the French ambassador in Athens le Comte de Moüy; and Foucart, the director of the French School, resolved most of the issues in less than four months. On 13 May 1881, Koumoundouros announced his intention to the Greek Archaeological Society to give France the right to excavate Delphi, and the 13 June 1881 was set as the date for signing the agreement.

40