Delphi Works of Ford Madox Ford (Illustrated) (424 page)

Read Delphi Works of Ford Madox Ford (Illustrated) Online

Authors: Ford Madox Ford

“Ah,” Sir William said genially, “that’s another queer point in Dionissia’s philosophy. I told her that any fool could run a publisher’s business successfully, but she just answered that in that case it was the business of a person who wanted to stand out from the ruck, to do it not only successfully, but well. So that what it comes to is” — and Sir William smiled as if at this he really did not know what had come over him—”what it comes to is that I’ve got to try to do something for literature.”

“But you’re becoming a moral prodigy!” Mrs. Lee-Egerton exclaimed.

“Oh, it isn’t that I am a reformed character,” Sir William hastened to exclaim; “it’s simply that Dionissia is a thorough-going idealist and extraordinarily concentrated. She can make you feel like a worm; she can make you feel anything she pleases by just thinking about it. She thought about the past glories of this place for years and years, until now she is reviving them. She thought about the past chivalrous achievements of the knights of her house, until—”

“I know what you are going to say,” Mrs. Lee-Egerton said. “She’s mooned on about this blessed old mouldy family of ours until she has turned up a new knight of her own to stick in the old house and go on being chivalrous in an up-to-date way.”

“I suppose that’s exactly what it comes to,” Sir William said. “But who would have thought that I should ever come to dropping money on poetry?”

“Oh, that’s what’s meant by

noblesse oblige,”

Mrs. Lee-Egerton laughed at him. “But I can tell you one thing: Whatever Dionissia is or isn’t or has or hasn’t, she’s got one thing, and that is her new knight remarkably well under her thumb.”

“Well,” Sir William said, “that’s the sort of thing that a man like me wants to make a man of him.”

“I am not saying that it isn’t,” Mrs. Lee-Egerton said. And just then Dionissia in a blue dress came under a ruined arch in the outer wall with the young architect behind her. Mrs. Lee-Egerton considerately contrived to carry off the young architect for a walk that she did not in the least wish to take, and Sir William and Dionissia wandered desultorily about the courtyard in the sunshine. They came at last under the central archway and amongst the rubble and the fallen stones of the hall on the left. They were holding each a hand of the other. Sir William touched with his foot a stone low down near the floor in one corner.

“It must have been just there,” he said, and Dionissia continued for him:

“That your head struck the wall”; and she added thoughtfully: “Yes, it was just about there.”

“It’s all awfully mysterious, my dear,” Sir William said. “At least it’s difficult to make it all fit in together. Either I went back to the fourteenth century because you wanted me to. Either the fourteenth century is still here behind a curtain. Or else it was you, sitting beside my bed and reading old chronicles, that just put the thoughts into my head.”

Dionissia went towards the broken window space through which the sunlight was streaming into the littered hall. She sat down upon the broken stonework and looked over her shoulder at the green valley.

“After all,” she said, in her deep and serious voice, “there have got to be mysteries, so we can take it one way or the other.”

“Ah, that’s so like the Lady Dionissia,” Sir William said.

Dionissia looked at him for a long time.

“You’ve made a great deal of difference in the world for me,” she said. “Everything is different. Everything seems much more real.”

“And that’s like the Lady Dionissia too,” Sir William repeated.

She looked at him still seriously. “That isn’t quite what I meant,” she said. “The point is, that before I saw you I used just to sit and to think for hours and hours about one thing and another. I didn’t want to have anything. I didn’t want to do anything. And then the moment I saw you I wanted to have you, and to get you back to life. And because you had the Egerton Cross clutched in your hand all the time, I began to think about that to keep myself from wanting you too much, and I got young Lee to bring me all the books he could possibly turn up about our family, and little by little I got it all constructed in my mind.”

“So that,” Sir William said, “it must have been you who made me dream, and not my spirit that went back, and I think I can prove that by one detail. You make the knights borrow money of a Jew Goldenhand in Salisbury. The Jews were all expelled from England from the time of Edward I to that of Oliver Cromwell. I looked that up in the

Dictionary of Dates.

So that shows that it was your imagination going wrong in a point. It can’t have been the real fourteenth century.”

“Oh, no, it doesn’t show anything of the sort,” Dionissia said. “You’d find if you’d looked up as many documents as I have, that there are at least a hundred instances of towns having orders sent to them to expel the Jews that were still living there even in the fifteenth century. If the towns were strong enough to do it with impunity, they just resisted the writs. They’ll show you the Ghetto at Winchelsea to this day.”

“So that I don’t get at you even on that point,” Sir William said. “I wish I could get the thing settled in my mind.”

She looked at him tenderly. “Oh, let it go at that,” she said, “and don’t worry your poor old head about it any more. We’ve got the whole world, we’ve got the whole of eternity before us; oceans of time, ages of space, and we’re the happiest people in the world.”

Sir William came close to her and looked over her shoulder at the broad, shallow valley that, all flecked with sunlight beneath the high clouds, ran away from under the broken window.

“But I should like,” he said, “to get first principles settled. And that’s a sort of first principle. If the fourteenth century is still there, behind a sort of curtain, it’s a whole new factor in psychics...

“Oh, my dear!” she said, “so it may be; but what does it matter? There’s you and there’s me, and there’s the sunlight and there’s the old place to do up. And there are plenty of other old places to see, and there’s plenty of work for us to do...”

“But are you perfectly certain,” Sir William said, with a touch of doubt, “that I shall make you happy? Won’t it be dull for you? I’m so much older, and I’m not at all intellectual.”

“Oh, stop all that,” Dionissia said earnestly; “that’s my adventure in life and that’s yours. We set out — we set out together, and we take our chances of what we find in each other. Happiness is a sort of thing you can’t put in a bank and draw upon. We’ve got to find it from day to day as if we were houseless wanderers upon the roads.”

She got down from the window and set her two hands on his shoulders.

“It was the same then; it’s the same now,” she continued. “Don’t you see? These are things we can’t take precautions about. We have our glorious moments and, even if our lives go to pieces, if disasters come, and ruin, and death, we shall have had our glorious moment, and that’s all there is in life, and that’s all there ever was. No! these are things we can’t take precautions about. We couldn’t borrow — even of a Jew Goldenhand, we couldn’t borrow assurance of happiness. But from the first moment I saw your face I said that you were the man that I could trust.”

“From the first moment I saw your face,” he said “you were the only person in all the world.”

“And yet I’m nothing.” She drew him closer to her.

“I’m nothing at all,” he said, and he put his arms round her shoulders.

“Ah! there you have the real mystery,” she murmured. “It’s this; it’s this and this that makes all the ages one. It’s this that we set the lance in rest for hundreds of years ago; it’s this that we publish encyclopaedias for to-day.”

“It’s this that I’ve come back from the dead for,” he said. She held him so tight that it was almost as if she shook him. She held her face back from his lips.

“It’s a beautiful world,” she said. “Say that it’s a beautiful world.”

“It’s beautiful,” he said.

“Say it’s as beautiful as the world ever was,” she commanded imperiously.

“It’s as beautiful! It’s as beautiful,” he repeated.

She closed her eyes.

“In the summer it will be very pleasant; the birds will sing, and we shall walk in the gardens. And in the winter we shall go into our little castle, and we shall sit by our fire, and our friends will come and we shall pass the time in talking and devising. And all around us there will be the oceans of time and the ages of space, like mountains and seas and forests that it shall take us many months to travel through.”

“I’ve heard that before,” he said.

“Yes, certainly you’ve heard that all before,” she answered with a gush of words. “It’s nothing new; it’s the oldest wisdom or the oldest folly. You will find it in Chaucer, because someone like your Lady Dionissia said it to him, or his heart did. And you will find it in the Bible, because there’s nothing else really to say. You will find it baked in the bricks that the Assyrians used for books and in the old sands of the desert and the oldest snow of the poles. It’s the only thing that’s worth saying in life.”

He strained her very hard to him; a robin flitting for moments on to the stones of the broken window held a worm in its bill, and surveyed them with its beady eyes. “I can’t find any words for it at all,” he said.

“Then we shall never know,” she whispered close to his ears, “which of us cares most. And that is the only mystery that really matters.”

The robin flittered away, the sharp flirt of its wings in starting making for a moment a little flutter of sound in the silence. From the distance there came the wailing sound of sheep bells over the sunny grass. The sheep were beginning to feed again.

THE END

EL

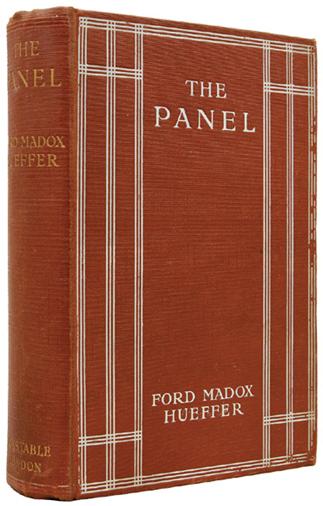

First published in Britain in 1912, and re-issued as

Ring For Nancy

the following year in America, this comedic novel was written, according to the author, as an “entertainment”, being a frivolous and light-hearted work, clearly directed at a popular audience.

The Panel

tells the story of Edward Brent-Foster, who is the youngest major in the English army, which status he has achieved by reading the works of Henry James. The protagonist explains that by threading his way through James’ intricacies, he had toughened his mind so that promotion had been no difficulty at all.

A bright and resourceful Irishman, Brent-Foster possesses the gift for deceiving his way out of situations, which of course always leads to hilarious repercussions.

Much of the comedy occurs in locations of bedrooms, one of which contains a picture mounted on the panel of the title, which pivots to open into a mysterious room behind. The action features typical features of farce, including concealment behind curtains and beneath beds, whilst Brent-Foster tries to evade the various obstacles that fall in his path.

Nevertheless, the novel exhibits a surprising deftness of skill that belies its apparent superficial nature, boasting a well-planned structure, amusing and intelligent dialogue and an entertaining pace.

The first edition