Delphi Works of Ford Madox Ford (Illustrated) (450 page)

Read Delphi Works of Ford Madox Ford (Illustrated) Online

Authors: Ford Madox Ford

Violet Hunt, c.1910, close to the time she first met Ford

CONTENTS

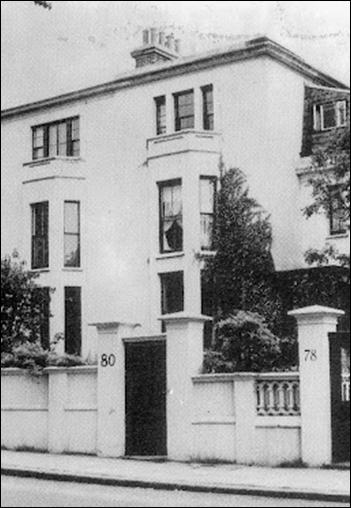

South Lodge, 80 Campden Hill Road — the location of the literary salon established by Hunt and where Ford lived with her for over eight years.

Ford with Violet Hunt, c. 1913

To GEORGE PLUMPTON McCULLOCH

MY DEAR GEORGE,

You will remember that some years ago, on a cool morning, we set out to walk some twenty miles from Vila di Goya into the Gallegos District of Galizia. You will not remember that I was in a flaming temper with you, because I did not tell you so. But you may keep still in your mind the fact that I had accompanied you into that valley of desolation and pink dust because you had told me that it contained not only the tin, cobalt, and petroleum for which you were searching, but also the descendants of a semi- mythical stud-bull that you called Le Gran Vasco. That had been my sole motive for coming to the Infernally dusty mountains in which you now reside and render hideous with your factories. And then, when I had reached Vila di Goya intent on seeing whether I could not improve my own stud- herd at Warley with some of the blood of that monster, I discovered that the Gran Vasco was not a bull, but a beastly bad painter — the only painter of your country of adoption. You only considered it a joke, and hardly apologised...

Well, in the heat of the noontide we sat under a rock and ate that infernal blue cheese that tastes like the smell of cats, and drank the infernal blue wine that is a mixture of warm leather and onion juice, and the plough-oxen of old Pompone Dedi were breathing down our backs, and the sea at the bottom of the valley was the colour of a blue meat-tin. And then you said:

“They’re putting up a statue to Sergius Mihailovitch in the Square at Flores... By Jove, why you don’t write a life of old Mac and call it the Dark Forest he was always talking about, I can’t see!’’

So here is the story of our friend, and I call it “The Dark Forest.” Mr. Lane, however, insists on re-christening it “The New Humpty-Dumpty.” Mr. Lane is without doubt wise. He is certainly tyrannical, and I am only a breeder of shorthorns writing to pass the time. At any rate, from your region of pink rocks, pink dust, blue cheese blue wine, and the distant sea that resembles a meat-tin, take a glimpse into this account of the pilgrimage of our good Mac — into the Dark Forest.

Yours,

D. C.

LORD ALDINGTON had been nagging at his wife during all the first two acts of the opera. That was why, during the pause, she had observed the foreign fashion and was walking round the foyer amongst crowds of cosmopolitan and mostly unpresentable people. Normally, Lady Aldington would have done nothing of the sort. She was as English as any woman could possibly be, even though she undoubtedly kept a thing so foreign as a

salon.

And, passing amongst all that crowd of foreigners who were all dark and who presented, nearly all of them, the appearance either of financiers with too many diamonds and too much linen, or of adventurers the state of whose linen showed that they hadn’t got enough and that they possessed no diamonds at all, Lady Aldington, with her highly trained aspect and her

tout ensemble

of a high blondness, presented all that she ever did present to the world in the way of emotions of discomfort. She had attempted to escape as it were from the British brutality of her husband, and she found herself in a place where all the voices were raised too loud. That was the main point about it — that and the air of stuffiness that all these people conveyed to her. She uttered the traditional British phrase: “Why can’t they open a window?” and then she turned her tall, thin body in its dress of grey silk slightly to one side, to pass between a Russian prince, whose hair was too highly oiled, and a Frankfort financier who had no hair at all. Her husband, who was six foot high, forty inches round the chest, and had a disagreeable heavy fair face, was unable to get through between the two foreigners. Thus Lady Aldington passed on alone. It was as if the crowd, which appeared to mass itself round the refreshment bars, where beer and odd-looking messes upon little saucers had by their aspect increased Lady Aldington’s feeling of discomfort — it was as if the crowd stopped suddenly, and she found herself in an almost empty corridor with square high pillars, walls covered with bluish mirrors, and red strips of velvet carpet underfoot. And suddenly her ladyship shivered. A voice had said:

“I tell you, Hanne, there’s no such thing as rice. Look at you and look at me.”

There stood before her — and just before a seat of grey velvet towards which Lady Aldington was making her way — there stood before her two beings unmistakably belonging to that country all of whose inhabitants regard the inhabitants of all other countries as something resembling niggers. The male wore dusty cycling stockings which showed that he must have been rickety in his youth, a tweed suit of grey that still showed the dust of the road. The little, dark woman had a thin, cheap blouse of pink linen, and a cycling skirt that heavy rain had shrunk till that too exhibited the fact that her thin legs were slightly bandy. She wriggled her small bowed shoulder-blades uncomfortably.

“I don’t fancy,” he added, “that anyone would imagine we had ever seen Camden Town.”

They had obviously been cycling well and truly, for at this point his eyes fell upon Lady Aldington just as he was wiping his brows with a handkerchief that resembled an oil rag. They were eyes of a singularly piercing and a singularly foreign black, and the lashes, that were actually coated with the dust of the road, gave them an odd touch of greyness. And the curled-up, black moustache, too, was thick with dust, so that he resembled nothing so much as a small French barber at whom had been thrown a bag of flour.

Losing for a moment her intense physical and mental discomfort now that she was out of the immediate pressure of other people’s bodies, Lady Aldington was standing perfectly still, looking down at the red velvet carpet that ran straight and brilliant beside the closed doors of the boxes. She had dressed because they had been dining with the Nugent-Beaumonts at the Rose. And it was part of her discomfort that she felt that her dress was torn half off her back. It was not, though in that year skirts were very full and trained. She had managed to get through somehow, so that all the little flounces of grey silk were intact and she shimmered. Indeed, with her brilliantly fair hair trained down over her ears, her pink and white skin, her delicately aquiline nose, her slightly severe features and the clear lines of her lips, the Lady Aldington, with her full skirt and its many little flounces spreading out from her waist — this figure of blondness, delicate shot silk, and slightly descending bare white shoulders suggested — as the fashions of that year were meant to suggest — a lady of the ‘forties. She was wondering if she could possibly put up with her husband for another year, and she stood perfectly still.

The voices reached her ears, but they did not really penetrate to her intelligence. She had forgotten the two cockneys, and she was standing with her side-face to them.

“These foreigners do get themselves up to look like us!” the man was saying. “Look at that piece of goods! Wouldn’t you say that she was English? Who’d think this was Wiesbaden?”

“Oh, she’s not English,” the woman was saying. “She doesn’t understand what we say.”

“Now, you make a note of this, Hanne,” the man continued, “if I forget to put it down in my ethnological notebook. That woman may be of any old nation. She may be Russian or German or French or Spanish. But the type comes true. It’s breeding does it, and feeding does it. Look at the way the head’s put on; look at the white flesh of the shoulders.”

It was at this moment that the Lady Aldington began to come to a sense of the place she was in. She was deciding that she must pardon her husband once again. She was aware that the cockney man was saying:

“Don’t you remember, Hanne, how Professor Hufnagel says in ‘Das Ewig Menschliche’... ‘Except for wide generalisation there is no such thing as Race. There are only Type and Environment. Cornelia of the Gracchi exactly resembled in Type the late Countess von Warschau, who was a Pole, and as equally resembled the Duchess de Dinont, whose mother was an Englishwoman, and whose father was French with an Italian mother.’... Now, look at that woman in front of us, Hanne! Look at her eyes, look at her nose! Look at her shoulder-blades! Some women’s shoulders when you see them you want to smack...”

Lady Aldington wondered vaguely what woman they were talking of, and then she heard a voice say in an undertone:

“My friend Pett, that is Lady Aldington.”

And she was dimly aware, out of the comers of her eyes, of yet another personality, apparently in evening dress, who was sitting on the seat that these two people had masked. She turned her back slowly upon them, and slowly and coldly she moved away. And she heard the voice of the cockney exclaiming:

“Comrade M.! Who’d have thought of seeing you here, and in these togs.”

Lord Aldington was bearing down upon her fast. His heavy face was full of a malicious gloom. But, looking over her shoulder, he exclaimed:

“Hallo! there’s Count Macdonald. I must introduce you to him when he has done talking to his friend.” He added, “He is the sort of person that you would get on with.”

And Lady Aldington knew that that was intended for another insult.